Laura Valeri’s debut collection, The Kind Of Things Saints Do (2002), won both the John Simmons Short Fiction Award and the Binghamton University John Gardner Award in Fiction; John Dufresne described it as “a daring and stunning debut.” The promise revealed in those stories has only deepened in the years since I first became acquainted with both Laura and her work. I have known her as both an academic colleague and a fellow fiction writer, and I’ve enjoyed discussing the art and craft of life with her. She is wise and funny and smart, a natural storyteller, a gifted teacher, and a devoted connoisseur of good food, good conversation, and good words.

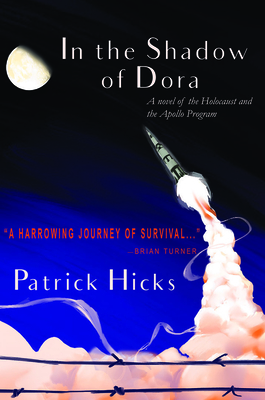

Her most recent title is Safe in Your Head (2013), a Stephen F. Austin Press prizewinner, a novel in stories featuring recipes and luck remedies for women during war time. I was grateful that she took the time to share how these dreamy, powerful tales came to be, how they commingle magic and history and the fine food of Laura’s native Italy in a collection of narratives both ethereal and earthy.

Interview:

Tina Whittle: Safe in Your Head is a work of fiction, but it is based on your coming to the United States at an early age. It is rich with the food and culture of the Italy of your experience, and also with the Italy of history before your time. How much research did you do into Italian history, especially the early to mid-twentieth century?

Laura Valeri: I did extensive sleuth work for this collection. The proverbs and the folklore remedies, for instance, had to be searched through various archives. I knew a few from tradition, but I also wanted to include less obvious ones. I also did research on my family history to sort out fact from myth. My grandfather fought during World War II. We knew he had been on the Russian front, and we knew that he somehow survived Italy’s change of allegiance from Germany to the United States while he was still entrenched with the Germans, because he recalled German soldiers using their bayonets to cut the hands of Italian soldiers who tried to hang on to their trucks as they retreated. When I began to check the facts against my family’s stories, however, some things didn’t add up. The change of allegiance came later. What he was remembering was the retreat from Russia, just ten months before. Memory is tricky. You can’t trust it. I had to ask a lot of questions, dig up a lot of newspaper articles and official documents.

It was exciting because I discovered my grandfather’s secret life as an activist. At seventeen, he was arrested for spreading fliers against Mussolini—which is why he ended up on the Russian front before he was even old enough to go to war. His brother, who was older, was taken and beaten to within an inch of his life. They all paid a great deal for their beliefs. I saw footage of what happened on that Russian front when the German lines were broken. It was carnage. Some 2,000 Italians died every day. Due to a snafu in military communications, Italian soldiers wore boots designed for the African desert. In addition to having to face an enemy that had superior weapons and that outnumbered them exponentially, these young men had to wrap cardboard on their feet to fight off frostbite.

It was exciting because I discovered my grandfather’s secret life as an activist. At seventeen, he was arrested for spreading fliers against Mussolini—which is why he ended up on the Russian front before he was even old enough to go to war. His brother, who was older, was taken and beaten to within an inch of his life. They all paid a great deal for their beliefs. I saw footage of what happened on that Russian front when the German lines were broken. It was carnage. Some 2,000 Italians died every day. Due to a snafu in military communications, Italian soldiers wore boots designed for the African desert. In addition to having to face an enemy that had superior weapons and that outnumbered them exponentially, these young men had to wrap cardboard on their feet to fight off frostbite.

In terms of the subject matter, I had intentions to write about the more subtle devastations of war, the effects that are visited on those who stay behind—the children, the wives, and mothers. I had a vague idea that my own life, though so removed from those events, also had been affected by my ancestor’s role in the two wars—and I was right, in more ways than I could anticipate. The year my father decided to emigrate to the US, Italy had just lost a pope, there was a brutal backlash after a government crackdown on an insidious mafia network, and a terrorist group called the Red Brigades infected and disrupted all socio-political dynamics. Then, the former Prime Minister Aldo Moro was kidnapped and executed. My father, like many others at the time, was afraid that we were on the brink of a Communist revolution. He used his international contacts to have his consultancy contract moved to a branch of Pfizer in New York, and we were gone.

At that time I was too young to detect what thread in the web of history my family had been caught up in, but as I was researching the facts, it became obvious that Italy has teetered between fascism and communism since my great great grandparents’ time. Of course, some of that struggle had to spill over on some of my family’s history, not just because my father felt compelled to leave when it looked like a Russian-backed terrorist group was about to take over the country, but earlier than that, when my great grandfather fought to free Italy from fascism. Partisans like my grandfather, who had helped Americans liberate Italy, became by and large persona non grata in the 1950’s, when McCarthyism and the Korean War was making Americans rethink their allegiances. I thought about this strange cycle, how we always end up facing the shadows we thought we left behind. It worked quite naturally, both on the personal and the historical level.

Family history provided inspiration for your work, along with the larger history of Italy, but inevitability is a dominant, connecting theme—the lives of these characters are on a predetermined track, their destiny laid before them. Dreams and premonitions occur, as well, as if future events have been locked in place as much as the past is locked. Characters must move through events, free will an illusion. Can you talk about the role of fate and chance in your work?

Flannery O’Connor once wrote that every good work of fiction must have an ending that feels both surprising and inevitable. And it strikes me that most of the realizations we have about ourselves are exactly that. Our circumstances and our character flaws are the forces that knock us around through our life’s journey, smashing us against our fate. In both my books I have explored the dance between two forces: the will power that we try to exert to control our destiny, and the forceful rush of life that is always invariably beating us back. For Safe in Your Head, those inevitable life forces are at work both externally, as the war and other violence unfolds, and internally, through the emotional scars one acquires. Those, too, become inevitable.

As I mentioned, the year my father decided to leave Italy, our former Prime Minister was kidnapped and executed. Both these events came on the early evening news, right after school let out. I remember looking forward to watching a serialized cartoon about Heidi, and here comes this news flash. The news anchors were weeping, talking with broken voices about Moro’s abduction. They showed footage of bullets holes in car windshields, police tape, chalk outlines of dead people, blood on the asphalt. It was positively frightening. As a storyteller, though, I couldn’t help but notice the juxtaposition of that family-friendly Heidi cartoon with this almost unconscionable violence. I remember George Bush Junior days after 9/11 telling us to go shopping. It was the same kind of shock, the same kind of helpless absurdity.

What I picked up from it was that sense of being caught up in something so large, that it seems futile to even try to pretend control, but in those circumstances that’s exactly what we try to do. In “Everything We Own Makes Us Safe,” the adolescent girl is trying to go on with life as usual, participating in an athletic competition, trying to be popular, or at least acceptable, but these violent forces erupt all around her and refuse to be ignored. They’re literally pressing against the gates of her school. As I was browsing for newspaper articles, I came across a picture of the abandoned Pirelli factory behind my family’s condominium, the one described in the story as littered with used syringes, condoms, and all things that represent the kinds of desperation that this girl’s social class is supposed to prevent. In the pictures the factory is crowded with protesters, police clutching cudgels trying to hold them back. I used to ride my bike on that street everyday after school. We all come to a point in time when we realize our mortgages, college degrees, and gated communities are at best flimsy barriers against the threat of poverty and violence, but for children who grow up during political turbulence those illusions fall early and hard.

I had a deja vu of this situation when I was studying in Iowa in 2001. I have a vivid memory of sitting in a bar, talking to friends, and watching the muted television showing footage of bombs falling on Afghanistan, and Tide commercials dotting the newscast. The conversation we were having was the most mundane possible, and I was aware that we were pretending normalcy to an extent that was unnerving, in some ways even morally deficient. And this was part of the theme of the story titled “Cold War,” in which the main character is trying to have a relationship with a man who is clearly unsuited to her because global warfare may not seem as bad when you have a partner. But, of course, it’s as inevitable that the couple fall apart as it is inevitable that the US attacks Iraq. These events, unrelated as they seem, are both emerging from the same script, and, yes, inevitable, in the sense that people can’t escape who they are, nor, most of the time, transcend the circumstances they are born into.

As you know, the story is also from the perspectives of my mother and grandmother, and both of them lived through World War II. How much control could these women be expected to have over their lives, when their husbands and sons were sent out to war? I don’t think that Italy, as a country, had all that much control over its destiny, either, with Hitler in Germany and Franco in Spain and war exploding all around. There’s an anecdote that my father the war enthusiast likes to tell about Mussolini’s famous boast of “eight million bayonets,” which referred, presumably, to the number of enlisted soldiers in the Italian armed forces. Apparently, when Hitler was considering whether to take on Italy as an ally, Mussolini marched every enlisted soldier in Rome across the street, then made them change their uniforms when they were out of sight, and sent them back around the corner to the back of the line. The real and verifiable story is that there was no such number of able fighting men at that time, and their bayonets were toys against the tanks and artillery that other powers boasted. Italy was in no shape to go to war with anyone, but had Hitler known this, I don’t think he would have kindly wrapped his arm around Mussolini and offered his protection. I’m sure either way we would have seen German tanks rolling on Italian soil. Aside all other obvious considerations about the immorality of Fascism, the fact remains that Italy’s geographical position was too strategic. Neutrality was out of the question. To this day, some survivors in Italy still refer to the German alliance as an occupation. History is complicated. Lives are complicated. The choices we make are often forced choices, the better of two evils. So, yes, I suppose that I do see inevitability.

I also sense a fluidity of time/space in your work. The past—as characters know it through stories and memories—seems as unfixed and open to change as the future. What “really happened” always open to how it is perceived, new information. Which seems truer to you?

A Buddhist I knew once told me, you can’t control what happens, only how you react to it. I’ve held on to that bit of wisdom. There was a lot of dreamwork and magic in some of the stories concerning my grandmother because I remember how she used to be able to talk about ghosts and premonitions with as much pragmatism as she would talk about someone who lived down the block who had moved to her hometown in such and such a year. I used to be amazed by these ghost stories, the fact that she really believed that her friend or cousin had unearthed a corpse and that it was still preserved after years, as I wrote in “A Kiss For Heaven’s Sake.” It was only when I started to write the collection that I realized why that is. For someone who has never experienced war except through television, it’s hard to imagine how surreal and reality-altering war must seem to those who experience it firsthand. If you saw that kind of violence, why would you not believe in magic, the devil, or living corpses? Isn’t war in all its atrocities just as challenging to human logic? To some degree, these sorts of superstitions and beliefs may be a defense against Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. I should also say that I am a believer of the supernatural. I don’t dismiss it off hand. But when I wrote the stories I was thinking of it not in terms of what really happened, but of how these women dealt with what happened, how they explained it to themselves in a way that made it possible for them to accept it and embrace the consequences.

This is the kind of thing that humans do all the time: we have a narrative. We explain the story to ourselves. As far as I understand from books I’ve read about memory and consciousness, our consciousness is all just a complex narrative-making machinery. As a fiction writer, I’m fascinated with the central role of story in our day-to-day life. In The Kind of Things Saints Do, every character faces some kind of incongruity that challenges the story of their lives as they have come to imagine it. Then something happens that can’t be ignored, and it forces that character to have to reconstruct the story, and to re-examine her complicity in life’s tragedies. That takes courage. In Safe in Your Head, the opening story is a mirror reflection of the last, but there we have the benefit of introspection. The narrative gets revised, sometimes a couple of times in the evolution of the telling.

This is the kind of thing that humans do all the time: we have a narrative. We explain the story to ourselves. As far as I understand from books I’ve read about memory and consciousness, our consciousness is all just a complex narrative-making machinery. As a fiction writer, I’m fascinated with the central role of story in our day-to-day life. In The Kind of Things Saints Do, every character faces some kind of incongruity that challenges the story of their lives as they have come to imagine it. Then something happens that can’t be ignored, and it forces that character to have to reconstruct the story, and to re-examine her complicity in life’s tragedies. That takes courage. In Safe in Your Head, the opening story is a mirror reflection of the last, but there we have the benefit of introspection. The narrative gets revised, sometimes a couple of times in the evolution of the telling.

What you’re describing here—the altering of perceived reality through an intentional act of re-structuring that may or may not have basis in logic—sounds a lot like magic, a word I’m using in its metaphysical sense. I kept coming to this idea myself as I was reading Safe in Your Head, where you include not only short stories, but also traditional Italian recipes juxtaposed with traditional Italian spells and charms. This movement from narrative to earthy specificity to magical intent was fascinating to me as a reader, both grounding me in the setting even as it disrupted my neat ideas about what was real, what was not. Not magic realism as much as realistic magic. Did you have any specific writerly intentions for structuring the book this way?

I like your wording, “realistic magic.” It makes me think of the way that I think of magic: it’s a reality for so many people, whether we want to ascribe to supernatural forces, or whether we see them merely as superstitions. For some of my relatives, believing in certain ways of doing things to bring out a lucky outcome was more of a tradition than a belief. For the Italy that my mother and grandmother grew up in, magic was part of everyday life. The line between praying to St. Jude for a miracle and peeling beans to see if you’ll marry a rich man is blurred, and a lot of the spells or remedies are associated with days of the years connected to saints with particular abilities for special miracles, so there’s this blurring with religion and witchcraft which most Italian Catholics aren’t really too concerned with. You’d have to step out of that world to see the incongruity. My mother considers herself a hard skeptic, for instance, and in most senses she really is. Yet she was always reminding us not to open an umbrella in the house, or to throw spilled salt over our shoulders. She firmly believed in prophetic dreams, even if never once have any of her dreams actually realized. If she broke a mirror she’d cry. I may have inherited that Janusian thinking, though for my grandmother and the women before her, magic was far more real, a necessity even. Curses are a big part of the culture, for instance. Again, my mother comes to mind, how she once fought with a contractor that she firmly believed had cheated her. She told us that she was cursing him to break his leg. The next week the contractor was on crutches. Do I believe it was my mother who did it? Yes! No! And I am absolutely positive and certain within my soul of both answers.

When I wrote Safe in Your Head, I was thinking that there needed to be that element of folk magic in there because it’s very much alive, even in modern Italy where no one would swear out loud to believing in ghosts or luck  charms, and yet everyone has a red coral pendant for good luck. Those beliefs and rituals are part of a cultural consciousness that doesn’t just disappear when you step on an airplane. You cannot separate Italy from it’s food traditions, proverbs, and daily rituals. I wanted to pluck out those that are unique to us, that haven’t already crossed the ocean and become transformed by other cultures. There is an alchemy in cooking. You can see it with anyone who has a passion for it: they touch and smell and treat each ingredient like it’s a venerable entity. If nothing else, food connects people, forms bonds, helps the brain link experiences to emotions that eventually turn into memories, and it’s no surprise to me that some recipes double as remedies, such as eating snails as a way to cement loyalty and bonds within a family. The fact that one of the recipes in there is a whole wheat banana pancake is emblematic of the character losing her connections, or at least, attempting to absorb culture through food. Incidentally, one of the worst moments of being an immigrant for me was realizing that I would never again taste the kind of crusty, wholesome bread that in Italy you can grab at any bakery. I think that there is something so elemental, so primal in the way that we prepare foods that is very much connected to the way that a certain type of magic infiltrates a culture, how magic takes on very different connotations depending which continent, which culture it was born in.

charms, and yet everyone has a red coral pendant for good luck. Those beliefs and rituals are part of a cultural consciousness that doesn’t just disappear when you step on an airplane. You cannot separate Italy from it’s food traditions, proverbs, and daily rituals. I wanted to pluck out those that are unique to us, that haven’t already crossed the ocean and become transformed by other cultures. There is an alchemy in cooking. You can see it with anyone who has a passion for it: they touch and smell and treat each ingredient like it’s a venerable entity. If nothing else, food connects people, forms bonds, helps the brain link experiences to emotions that eventually turn into memories, and it’s no surprise to me that some recipes double as remedies, such as eating snails as a way to cement loyalty and bonds within a family. The fact that one of the recipes in there is a whole wheat banana pancake is emblematic of the character losing her connections, or at least, attempting to absorb culture through food. Incidentally, one of the worst moments of being an immigrant for me was realizing that I would never again taste the kind of crusty, wholesome bread that in Italy you can grab at any bakery. I think that there is something so elemental, so primal in the way that we prepare foods that is very much connected to the way that a certain type of magic infiltrates a culture, how magic takes on very different connotations depending which continent, which culture it was born in.

So, here’s a final question: what’s next for you as a writer?

The ancestors are still calling. I have a great uncle from my father’s side who had significant success as a poet in Italy: Diego Valeri. Some of his poems are still featured in school texts. I received an invitation from a library curator in his home town of Piove Di Sacco, who also works with the Cini Foundation, which is preserving many of Valeri’s works and artifacts, to write an examination of my great uncle’s friendship with poet Ezra Pound through a collection of their correspondence. I was quite surprised to learn that they were friends. My great uncle had to flee Italy under Fascism because of his progressive political views. Several influential entities had to organize a rescue mission to scuttle him out in secret while the SS was searching out his job and home to arrest him. Ezra Pound, on the other hand, was an outspoken anti-semite who wholly and openly supported Mussolini. So I’m curious to find out what kind of friendship these two might have had. There’s a good story in there somewhere, I’m sure of it.