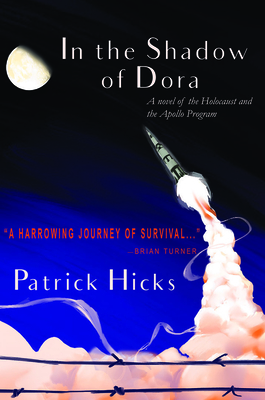

In ordinary times, Patrick Hicks’s new novel, In the Shadow of Dora (Stephen F. Austin University Press), would be read as a gripping, beautiful book about the Holocaust and the Space Race—two events protagonist Eli calls “[t]he great poles of his life … the darkest and brightest.”

It is a novel carefully plotted, intensely researched. “Dora” refers to Dora-Mittelbau, a facility that is an offshoot of Auschwitz where prisoners like Eli were forced to build the V-2 bombs Hitler hoped would turn the tide of the war. In parts, it reads, somewhat necessarily, almost like nonfiction, while in others—often in its darkest, hardest-to-read-parts—it reads more like poetry. Hicks writes of nights “machine-gunned with stars,” of “wild world[s] of competing mouths and teeth.” Violence and rhythm; a delicate dance. Even in ordinary times, an outstanding novel.

But these are not ordinary times. I read Dora this summer, during the first few days of mandatory self-isolation after fleeing my apartment in Manhattan for the midwest. I’d left behind a city that, like many others, was broiling with racial unrest and political tension, its energy suddenly frantic after months of deathly quiet lockdown. And though we read to be transported, it soon became clear that the world Eli describes in the book, both during and after the war, had ceased to feel so very different from my own—the innocent trampled underfoot by a nation inclined toward progress at the cost of justice.

Whether subconsciously or by chance, Hicks has delivered one of those books that comes exactly when we need it. It explores, yes, the poles of Eli’s life, what Hicks describes as “the depths of hatred and the heights of ambition” when we talked over email. But it also spends a good deal of time somewhere in a murky middle ground—the same Nazi scientists who ruled Dora so cruelly were later recruited by the American government to help get us on the moon. And it is here that the novel’s power, and urgency, lies. It is a timely reminder of that oft-repeated promise: never again.

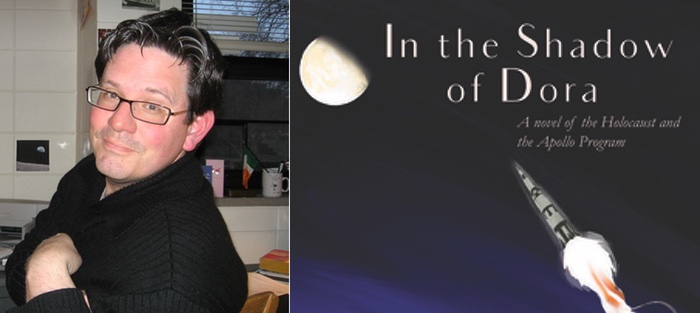

Patrick Hicks is the author of The Commandant of Lubizec (you can read an FWR interview about that book here), The Collector of Names, and Library of the Mind. He is a Professor of English at Augustana University and a faculty member at the MFA program at Sierra Nevada University. His new book is In the Shadow of Dora: A Novel of the Holocaust and the Apollo Program.

Interview:

Hannah Redder: I think readers will agree with me that the opening pages of In the Shadow of Dora are quite unsettling. Sometimes it’s easy, and maybe comforting, to think you know all there is to know about the Holocaust, yet here’s this totally unknown thing—Dora-Mittelbau—within that landscape, that you’re approaching for the first time with the protagonist, Eli. Did you have a similar experience in your first dealings with Dora? A feeling of “How did I not know about this?” What made you decide to write about it?

Patrick Hicks: You’ve hit on something that is very true of the Holocaust in general. Most people think they know it well, but it’s so much bigger and complex and heartbreaking than is usually understood. There’s so much to know. Whenever I do a reading and mention certain aspects about what happened in Europe under Nazi tyranny, I almost always have people come up to me afterwards with follow up questions. There is this deep sense of surprise—how did I not know about this? This could happen when I talk about the T4 program, or the Einsatzgruppen, or Operation Reinhard, or a fancy day spa outside of Auschwitz that was used by the SS guards to relax. I feel compelled to shed light on areas of the Holocaust that aren’t lodged in the public imagination as vividly as they should be. That’s the job of the writer—to shed light.

It may surprise people to learn that Nazi Germany was the first country to put an object made by human hands into space. They developed the world’s first functioning rocket, and they used it as a weapon of war. The V-2 was mass produced in a secret underground concentration camp. It was built by slave labor. In fact, America got to the moon partly because of the Nazi scientists we recruited after the war. Rather than prosecute them for crimes against humanity, as we should have done, they were given research facilities to make rockets and high-performance aircraft. These men created the mighty Saturn V that carried our astronauts into space. This isn’t something our nation wanted to advertise during the Cold War—it would spoil the glittering image of the moon landings—but what happened in Dora-Mittelbau is directly tied to the Apollo Program. When I first learned about this connection, I knew that I wanted to write about it. I wanted to shed light. And now that In the Shadow of Dora is finished, readers are saying, as you pointed out, “How did I not know about this?” There are reasons for this blind spot, and I unpack them in the novel.

Unlike your first novel, which follows a perpetrator of the Holocaust, Dora follows a survivor whom we follow into the rest of his life, over a course of three decades or so. How did the experience of writing this character, over this increased period of time, differ from that of your first book?

Unlike your first novel, which follows a perpetrator of the Holocaust, Dora follows a survivor whom we follow into the rest of his life, over a course of three decades or so. How did the experience of writing this character, over this increased period of time, differ from that of your first book?

I really appreciate this question because it gets to the heart of the book. In order to write about the historical connections between Dora and NASA, I wanted to have a character—Eli Hessel—who experienced both places. He’s forced to build rockets in Dora-Mittelbau as a prisoner, and then he’s recruited to do similar work in the 1960s for Apollo. This links the two events through a single character, yes, but it also allowed me to explore the lingering trauma that Holocaust survivors are forced to carry. Although I touched upon what it meant to be a survivor in my first novel, it wasn’t the primary focus of that book. I was more interested in bringing a death camp to life. Notably, The Commandant of Lubizec doesn’t end with the commandant having the last word—it’s a survivor who has the last word. That was intentional on my part.

While I was working on Dora, I interviewed a number of Holocaust survivors and the more that I considered the lasting trauma of genocide, the more it became clear that this needed to be part of Eli’s story. How do the ghosts of the Holocaust haunt him? How does trauma shape his world? And so, this becomes one of the threads of the narrative itself. In the Shadow of Dora isn’t just about the real-life connections between Dora-Mittelbau and the Kennedy Space Center—it’s also a novel about living with the crushing weight of the Holocaust. How do you pick up the smashed pieces of your life and move forward? How does a person do this? The bravery of the survivors just astounds me.

You said in an interview that the Holocaust and the moon landing are common fodder for conspiracy theories because they’re too immense to even seem possible. I don’t know about you, but I’m getting a whiff of that now around COVID-19. What do you think is our responsibility as writers during times like these?

I think it’s our obligation to speak the truth, especially if it’s unpopular or unwanted. The nature of conspiracy theories is to undermine reality and offer a version of the past that never happened. It makes believers feel as if they have special knowledge and that they’re somehow smarter than the rest of us and “in the know.” Holocaust denial is a particularly insidious example of this, and it’s fueled by anti-Semitism. Those that deny the Holocaust, and those who believe the moon landings were faked, use the word “hoax” to explain these historical events. It’s a word our current President favors for any news that he finds too critical. Calling something a “hoax” is a weaponized rejection of reality.

When it comes to the Holocaust and the Apollo program, we have an added sense that they both seem impossible. These two events represent the worst of what we are capable of doing to each other, and also the best of what we are capable of doing together. They are the poles of the human condition. They represent the depths of hatred and the height of ambition. It’s easier to say that Auschwitz and Apollo didn’t really happen because that means you don’t have to confront the reality of what it means to be human. It’s no surprise to me that the two greatest events of the 20th-century—the Holocaust and the moon landings—are labeled, by some, as hoaxes. To be clear, I think there is a big difference between saying Apollo 11 didn’t happen and saying the Holocaust didn’t happen. One is a laughable denial while the other is deeply sinister, as well as morally repulsive. As Elie Wiesel once said, “To forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.” That’s what Holocaust denial is.

Along those lines, there’s a line in the book’s second half that reads, “Heroes … cannot have a dark past. If the truth is troublesome, the truth needs to be revised.” You’re referring here to the involvement of former Nazis in the programs that got Americans on the moon, but the sentiment feels equally, perhaps eerily, relevant to us now. In a time when we’re having so many hard conversations about the foundations on which our country is built, what do you think we can learn from that situation? Was this an intentional exploration? Perhaps an unavoidable one?

I finished the first draft of this book in early 2016—long before the election—so it’s just happenstance that there’s an echo with current events here. But maybe during the editing of the novel I subconsciously thought about these things? That’s possible. The fact that the Nazi scientists had their pasts bleached clean was something I very much wanted to explore. Even today little is known about Dora-Mittelbau and the roles that Wernher von Braun, Kurt Debus, and Arthur Rudolph had in the production of the V-2s. They avoided jail time and were able to start new lives in America thanks to their expertise in rocketry. Who wants to be reminded of the Holocaust when Apollo 11 is on the launch pad? When von Braun pointed to the moon and said that it was within our reach, who wanted to be reminded that he built rockets that killed thousands of people in London and Paris? No, the United States made a Faustian bargain with these scientists: “build us the best rockets in the world and you can live in freedom. We’ll ignore your past. It will be sanitized.” This is one reason why Dora-Mittelbau hides in shadow today. During the war it was a secret because of what was built there; after the war it remained secret because of who worked there.

The moon is of obvious fascination here, both in the larger public imagination and in the main character’s. Do you share Eli’s interest? What about the moon, do you think, is so alluring to us, particularly within a story like this one?

I grew up in the 1970s and because of this I’ve always been fascinated by Apollo. When I was ten we took a family vacation to the Kennedy Space Center and I was just mesmerized by it all. The moon fascinates me, yes, but it’s linked in my imagination to those spidery lunar spacecrafts touching down in places like the Sea of Tranquility and the Ocean of Storms. Our moon is such an oddball in the solar system. I mean, compared to other moons, it’s absolutely colossal. It’s more like a twin planet than a moon. Life as we know it may not have developed without its constant pull on our tides or the fact that it has protected us from asteroids. You just have to look at the surface to realize how much punishment the moon has taken. And yet, it’s so beautiful. It hangs above us. Every language has a word for it—Luna, Kuu, An Ghealach, Bulan, Al-Qamar—and it’s been the muse for so many legends and myths. It’s hard to imagine the stars without the friendly “night sun” (to use a Lakota idea) lighting the darkness.

And then when I think of the mind-blowing bravery it took to travel there? The moon is some 240,000 miles away and that’s just such a staggering distance. If the earth was the size of a basketball, and the moon was the size of a baseball—these are roughly accurate sizes—you’d have to place them twenty-three feet apart. That’s how far the astronauts had to travel. And they had this tiny little angle to enter lunar orbit. If they overshot, they’d skip out into outer space never be seen again, and if they undershot they’d smash into the moon. To this day, landing on the moon remains the greatest journey we’ve undertaken as a species.

So yes, I’m fascinated by it. In my office I’ve got a photo of the earth taken by Apollo 8. We live on such a breathtakingly beautiful planet. It’s so fragile, hanging there in the dark void. I’d love for us to see the earth from that distance once again. It would give us much needed perspective.

Your chosen subject matter demands a good amount of research, and I know you did your fair share for this with visits to Dora and the Kennedy Space Center, among other things. Could you tell us a little about those experiences, and also about how you balance research with other parts of the process? Do you research first, write second?

A great deal of research went into this novel, and that included lots of time at the Kennedy Space Center, the Johnson Space Center in Houston, and the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville. I also went to Germany on two different occasions to visit Dora-Mittelbau and get into the ruined tunnels. I’m so grateful to the granting agencies that allowed me to do this because I could see the settings more clearly and bring the narrative into sharper focus.

For novels like this, I do a lot of research first, then I travel to the setting, and while I’m there I hunt for stories. I fill up entire notebooks with observations. I talk with guides, I take photos, and I imagine what my characters might see. When I’m back in my office I draft, and edit, and fuss about craft. With this particular novel, I spent a lot of time at Dora-Mittelbau because I wanted to get the story right. That was very important to me. It’s a challenge to make the past feel present.

All of this research means that I can show photos to an audience whenever I do a reading. There is deep interest in the Holocaust out there, and I often feel that my job is to help people understand it a little better. If my novel can act as a doorway into awareness, all of the hard work has been worth it.

I know you said that while writing The Commandant of Lubizec, you worked on a collection of poetry at the same time to help alleviate the stress of writing such a difficult narrative. Was your process the same for this book? If so, do you mind telling us what you worked on?

In some ways, this was an easier novel to write—at least psychologically. The Commandant was just soul crushing to write. There were so many characters that I cared about, and so many of them died. At least with Dora, I knew from the outset that it was a story of survival. That buoyed me a bit, especially when terrible things began to happen to Eli. He’s a good and decent man. I like him a lot.

When things did get too bruising for me, I’d step away from the narrative and turn once again to poetry. While I worked on Dora I also wrote Library of the Mind: New & Selected Poems. That helped. I guess I need a counterweight to, as you say, alleviate the stress. I’ve already started mapping out my third novel about the Holocaust. It’s going to be about gender and violence—specifically women in the Nazi party—and I anticipate that this novel will round out my trilogy of work on the Holocaust. I’ve already got the story in my head. I just need to return to Germany in order to see it more clearly.