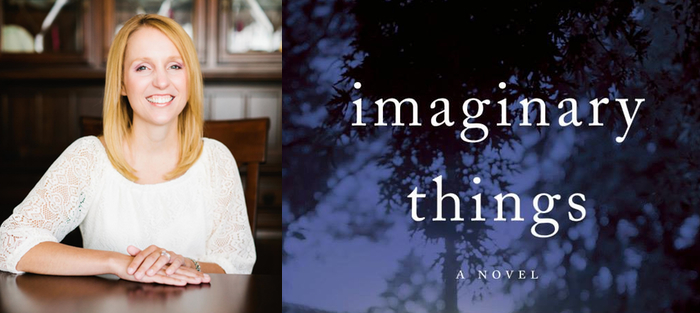

Andrea Lochen and I first met as newly-minted University of Michigan MFA students in 2006. A couple of affable Midwesterners, we quickly struck up a friendship over books, snow, and the delights of cheese. I am happy to say that our friendship has only deepened as our lives have progressed and our writing matured. For the past eight years Andrea and I have swapped critiques, career advice, word counts, and encouragement, and I count myself lucky to have been one of the first readers for her delightful new novel, Imaginary Things, just released by Astor + Blue. The tale of a single mother troubled both by the specter of her ex and her young son’s fantasy life, the novel is a wonderful dance of playfulness and threat, pragmatism and whimsy.

In addition to Imaginary Things, Andrea is the author of The Repeat Year (Berkley, 2013), which won a Hopwood Award for the Novel prior to its publication. She has served as fiction editor of The Madison Review and taught writing at the University of Michigan. She currently teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Waukesha, where she was recently awarded UW Colleges Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching.

Interview:

Rebecca Adams Wright: An April 1st publication day! You promise that you’re not fooling, right? I’m not going to open my brand-new copy of Imaginary Things only to find that all the pages are blank?

Andrea Lochen: I thought that was really ironic too, that the book was coming out on April Fool’s Day. It does sound sort of like a bad joke, but hopefully you won’t open it and find that the pages are blank and you have to imagine it for yourself. [Laughs.] So I’m pretty sure that it’s legit, but fingers crossed right?

Yes! But In all seriousness: the premise for Imaginary Things—that a young mother can see her four-year-old’s imaginary friends—is wonderfully inventive. How did it come to you? I know that often when I’m working on my own stories an unlikely situation will occur to me, but it can take a while for all the pieces to come together so that a story coalesces around that initial spark. Did you know right away where you wanted to take your idea?

I wish I could claim that I did, but unfortunately I did not. I’m one of those writers who likes to come up with a fantastic premise, kind of a “what if?” question, but then I have no idea what it means or what I’m going to do with it at first. I actually came up with the idea for Imaginary Things at the University of Michigan when we were in the MFA program together. It was a short story, initially, with the same magical premise but a different protagonist and a different setting. I struggled with the short story, and with each revision it became longer and longer, because ultimately I think it wanted to be a novel; the idea couldn’t be contained in just one story. All the pieces finally came together for me when I figured out what was at the heart of the novel: why Anna could see her son’s imaginary friends and what the significance of that was, both in terms of plot and theme.

I’m glad you mentioned the speculative element at the heart of this story, since magic plays a big part in both your novels. I delight in this, of course, since my own story collection, The Thing About Great White Sharks (Little A, 2015), is chock-full of magic and fancy and bizarre science and what-have-you. I have come to believe that my stories are most true when they lean outside of the bounds of our everyday lives. It is not lost on me that both Anna (of Imaginary Things) and Olive (protagonist of The Repeat Year) have a great need to refocus their lives. The magic they experience seems to force them to evaluate the choices they are making. Do you see the speculative element in Imaginary Things working that way, as a kind of catalyst for change? What else makes the magic compelling, even necessary, to you?

I’m glad you mentioned the speculative element at the heart of this story, since magic plays a big part in both your novels. I delight in this, of course, since my own story collection, The Thing About Great White Sharks (Little A, 2015), is chock-full of magic and fancy and bizarre science and what-have-you. I have come to believe that my stories are most true when they lean outside of the bounds of our everyday lives. It is not lost on me that both Anna (of Imaginary Things) and Olive (protagonist of The Repeat Year) have a great need to refocus their lives. The magic they experience seems to force them to evaluate the choices they are making. Do you see the speculative element in Imaginary Things working that way, as a kind of catalyst for change? What else makes the magic compelling, even necessary, to you?

One of the things I love about you, Becky, is that you really get my books. You are such an astute reader that you come up with a question like this because that is exactly it: magic is a catalyst for change in both situations. In my first novel, The Repeat Year, when Olive wakes up on New Year’s Day and discovers that she has to relive the previous year of her life, she is forced by this magical apparatus to see her life through new eyes and to make different choices and different decisions. In the case of Imaginary Things, when Anna starts seeing her son’s imagination, which she doesn’t recognize as such right away, she’s forced to reevaluate her conception of motherhood and to look at her son a little more deeply.

I really like taking a magical premise and using it to jumpstart the action in a novel and having it go in unexpected directions that readers don’t typically find themselves. I like giving a character this great opportunity for change but them having no idea what to do with it. It’s a mystery to them; it wasn’t straightforward for Olive in The Repeat Year, to figure out what to change, and it’s very frustrating and bewildering to Anna what she should do with her ability to see her son’s imagination. It’s a magical premise that has no script for them, no rules or guidance; they kind of have to muddle through it and figure it out on their own, which is kind of how life is, right? Even if we were granted one of these magical opportunities, it would still be really hard to figure out what to do with it.

I like that you mentioned danger and going into this without a script. There are some dark themes in this book, about trust, and betrayal, and personal safety. But one I keep coming back to is mental illness. Anna’s former partner, Patrick, suffers from bipolar disorder and her mother is clearly unstable. You handle this complex issue with such humanity—I’m wondering if it was difficult to write these scenes, and what kind of research you had to do to feel like you had done justice to the affected characters.

It was challenging to write Patrick as a complicated, sympathetic character. I did a lot of research on bipolar disorder, but ultimately what was most useful to me was having readers give me feedback on scenes with Patrick. I felt like there was this very fine line I was walking between having him be a character who was unstable and dangerous enough for Anna to want to get sole custody of her son, David, but also a real person with both virtues and flaws, and not just a bad guy.

No paper villain.

Exactly! I wanted him to be sympathetic and for us to look carefully at this character who was cruising along in life and then suddenly in his early twenties has the rug pulled out from under him when he develops this mental illness. I wanted to show that he is someone who is struggling, someone who loves his son very much, and loved Anna very much, but can’t quite get his life together. So, thankfully, I had great readers—yourself included—who gave me feedback on his character, which was very helpful to me.

I’m also very interested in the relationship between Anna and her mother. Kim is so very different from her daughter, and her failures as both a parent and a person brought to my mind the “likeability” problem—essentially, the idea that it is more important for certain female characters to be “nice” than interesting, which is something not typically demanded of male characters. Is this an issue that came to mind at all while you were writing the scenes between these two women? Kim is very interesting, but she sure as hell isn’t “nice.”

No, she is not! I have found that the “likability” quandary that we force on our female characters typically has more to do with the protagonist. So in some ways, I did feel pressure for Anna to be “nice” in order for readers to feel like they can connect with her more.

Because we want to identify with Anna.

Yes, so that is very important. However, I feel like with the supporting female characters you can get away with a lot. They don’t have to be likeable and can do pretty awful things. For me, Kimberly was a really interesting character to write because she was so not maternal, and actually quite cold and hard to understand. As I did with Patrick, I had to walk that fine line of still making her empathetic. I hope there are a few moments in the novel, where readers look at her and think, “Wow, maybe she is struggling and maybe she does deserve our sympathy. Maybe we don’t fully understand her.” We see her from a couple of characters’ eyes. So even though Anna has many reasons to dislike her mom, we also see that Kimberly’s parents, Duffy and Winston, still love her and have hopes for her. So you have to wonder, Is Anna looking at her with a biased view?

It brings into question how reliable you can be when evaluating your own parent! Okay, let’s switch gears for a second. One thing I love so much about this novel is that we have the rare opportunity to get inside Anna’s head, while she has access to David’s. Character is my meat and drink and this is two characters for the price of one. Talk a little about Anna, and what it was like getting to know a character with this wonderfully bizarre access to another person’s mind.

It brings into question how reliable you can be when evaluating your own parent! Okay, let’s switch gears for a second. One thing I love so much about this novel is that we have the rare opportunity to get inside Anna’s head, while she has access to David’s. Character is my meat and drink and this is two characters for the price of one. Talk a little about Anna, and what it was like getting to know a character with this wonderfully bizarre access to another person’s mind.

It was really fun. One of the things I like about Anna, what makes her so enjoyable to spend time with, is that she’s very down to earth about it. I feel like you could give this magical ability to, you know, one thousand other parents, and they would do totally different things with it than Anna does. Instead, she’s very matter of fact about it when she first starts seeing David’s imaginary friends. Initially, she does Internet research, trying to figure out, for example, “Are there giant lizards running around this rural Wisconsin area? No? Okay, well am I going crazy then?” She deals with it in a very straightforward way.

Can I just say that’s one of the things I like most about Anna, that the first thing she does is Google this? That’s exactly what I would do!

I think so too! When I was writing that scene, I actually did Google it to see what would come up in the results.

Oh my goodness, what did you find?

Oh, there are all sorts of great urban legends and sightings of mysterious creatures in Wisconsin: ghosts, Bigfoot, and even something called the Hodag, which I briefly mention in the book. But back to Anna. She is someone who is very creative and had a very active imagination as a child, so after the initial shock, she really relishes the fact that she sees her son’s imaginary friends. It was fun to imagine what it would be like if I had the ability to see a child’s imagination.

Let’s talk about the imaginary friends themselves. You mentioned, without giving too much away, that one of them may be of the “dinosaur-ial” variety. The title of my own collection may indicate my glee at discovering that there are weird animals roaming around in this novel. Was it a struggle or a liberating experience, having free rein to write whatever a child might dream up?

It was very liberating. From the very beginning, when I conceived this story, I knew there were going to be dinosaurs. They were always going to be a part of the story, and it was so much fun writing the scenes when David is playing with them. At one point, I even found myself watching YouTube clips from the movie Jurassic Park of a T-rex vocalizing as part of my “research,” which was pretty entertaining. I did have other imaginary friends thought up for David, who ended up not making it to the final draft because it just got to be too much. But I wish I could have populated the novel even more with other imaginary friends, because that was really fun to write. I myself never had an imaginary friend, although as kids, my sister and I used to play elaborate games of make-believe and pretend. I’m jealous of kids who did have them!

I didn’t have one either, but this novel makes me wish that I did! I want to ask you, too, since you brought up some characters that didn’t make the cut, about your process while writing this novel. I think most authors are sort of obsessed with how other writers work, and I’m no exception. How did you tackle this novel? I’m interested to know if any part of the process differed from the way you approached writing The Repeat Year, the early drafting of which I remember from our time together at U of M.

I didn’t have one either, but this novel makes me wish that I did! I want to ask you, too, since you brought up some characters that didn’t make the cut, about your process while writing this novel. I think most authors are sort of obsessed with how other writers work, and I’m no exception. How did you tackle this novel? I’m interested to know if any part of the process differed from the way you approached writing The Repeat Year, the early drafting of which I remember from our time together at U of M.

It was a very different experience for me at the beginning, but towards the end I started to kind of return to my same process. At the beginning, I patted myself on the back because I had an outline for Imaginary Things, which was light-years ahead of where I was with my first draft of The Repeat Year, which I just dove headfirst into. For The Repeat Year, the first and second draft looked nothing like each other. It was a huge, reconstructive surgery. So for Imaginary Things, I thought I was so clever—I had written one novel before, and I had an outline, I was going to pound this thing out really quickly and it would be great. Well, I still had to do several drafts. Because as I stated earlier, when I come up with a magical premise I don’t always know what it means right away. I have to chip away at it. So until I could find the heart of the novel, which took me a few drafts, I couldn’t pare down the scenes and have just the essential elements—conflicts, character transformations—until I knew what it all added up to. And it took quite a while. So I’d like to say that the process started out a bit different, because I was more focused, but in the end it still took me several drafts and several readers.

The good news is I feel like I’m getting better at revising and not expecting perfection from myself. I’m realizing that it’s going to take me a few drafts to write a good novel. And it’s definitely going to require some good trusted readers to help me along the way.