Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

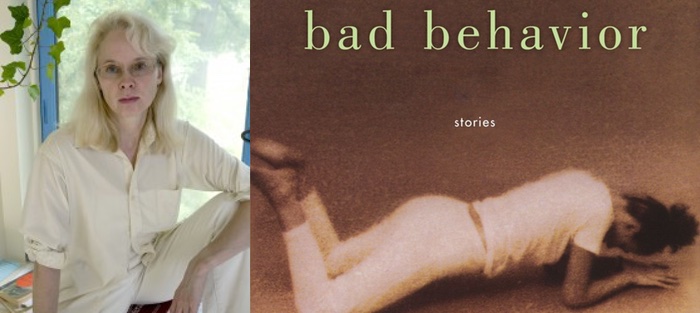

In today’s feature, Emily McLaughlin talks with Mary Gaitskill about her early years at the University of Michigan, how she approaches her craft, and gender and writing. This interview was originally published on May 9, 2011.

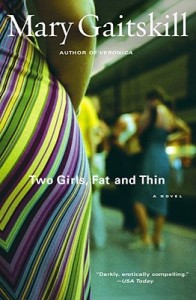

Mary Gaitskill was born in Kentucky and received her B.A. from the University of Michigan, where she was the recipient of a Hopwood Award. Her first book of stories, Bad Behavior, was published in 1988. She is also the author of two other collections, Because They Wanted To and Don’t Cry, and two novels, Two Girls, Fat and Thin and Veronica. Her short fiction has appeared in numerous anthologies, including Best American Short Stories (1993 and 2006) and The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories (1998). The 2002 film Secretary, starring Maggie Gyllenhaal and James Spader, is based on her story of the same title from Bad Behavior.

Gaitskill is also the recipient of many literary accolades, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a PEN/Faulkner Award nomination for Because They Wanted To. In 2005, her novel Veronica was a National Book Award nominee, as well as a National Book Critics Circle finalist. She is currently a 2010 Cullman Center Fellow at the New York Public Library.

In February of 2011, Mary Gaitskill returned to her Alma Mater as part of the University of Michigan’s Zell Visiting Writers Series. I had the pleasure of spending the afternoon in her company in Ann Arbor, including a lunch with MFA students, a roundtable discussion in the Hopwood Room, and this one-on-one conversation. Listening to Mary in person had a similar effect to rereading her books: I walked away from each a wiser woman, with a deepened understanding of and curiosity for the world I’m traveling through and the people I’m passing by.

Interview:

Emily McLaughlin: Because we’re sitting here in Angell Hall, at the University of Michigan, my first question is this: Have you gone back to read your winning undergraduate Hopwood Manuscript in the Hopwood Room?

Mary Gaitskill: I have. It was a few years ago. I think my story “The Woman Who Knew Judo” holds up pretty well as a young story. The others are a bit embarrassing. But that’s okay.

I went back and read it. The three stories had all of your trademarks: the steady hand of your sentences, the humor, the intelligence. Your voice and style were very apparent. Did you try to publish those stories?

I tried to publish “The Woman Who Knew Judo” and got nowhere with it.

Are you able to remember writing the initial drafts and where you were emotionally at that time?

Well, it was a terrible time. I remember that. I entered the Hopwood a number of times and didn’t win.

Wow.

They were probably bad stories. I don’t remember them anymore. Though there was a story of mine, “Something Better Than This,” that was published [in the late 1970s] in a small Canadian magazine called Branching Out. An online publication called Fictionaut recently approached me about republishing that first story of mine and so I gave it to them. It’s actually pretty good. It’s young, certainly not how I would write now. A lot of the stories I wrote in Ann Arbor were really bad. I try to remember this when I’m teaching because most of my stories would not have stood out to me at all as a teacher. They don’t show exceptional promise. What they do show is someone who is aware of style, and most students are not. Literary style is quite important to me; it’s not superficial, it’s the means through which your content becomes known. I clearly had a sense of style and was trying to work with it. But other than that, I wrote pretty average undergraduate work.

They were probably bad stories. I don’t remember them anymore. Though there was a story of mine, “Something Better Than This,” that was published [in the late 1970s] in a small Canadian magazine called Branching Out. An online publication called Fictionaut recently approached me about republishing that first story of mine and so I gave it to them. It’s actually pretty good. It’s young, certainly not how I would write now. A lot of the stories I wrote in Ann Arbor were really bad. I try to remember this when I’m teaching because most of my stories would not have stood out to me at all as a teacher. They don’t show exceptional promise. What they do show is someone who is aware of style, and most students are not. Literary style is quite important to me; it’s not superficial, it’s the means through which your content becomes known. I clearly had a sense of style and was trying to work with it. But other than that, I wrote pretty average undergraduate work.

Do you remember any point or instant in your life when you felt you had something special? That you were gifted?

I knew that writing was the only thing I cared about outside of my personal life. I knew it was the only thing I was good at. I did briefly experiment when I was a teenager with painting. I left home at an early age and there was simply no way I could afford painting. I couldn’t afford canvas and paint and they were bulky. For writing I only needed a notebook and pen. I didn’t even have a typewriter. So that was part of it. But I wasn’t told I was talented very much. In fact, when I was here there was a particular contest which, unlike the Hopwood, you needed the recommendation of a professor to even enter. So I went to my creative writing teacher and he said, “No, you’re not good enough.” And I said, “Oh, okay.”

Did you have any contact with him in the future?

Yeah. When I came to read here the first time, back in ’89, he was elderly at that point, and he actually came in a wheelchair. He was clearly so happy I had done well. He wasn’t trying to be mean, he was simply telling me the truth. He didn’t think I was good enough.

There are so many students who want to write. As a teacher, do you ever believe in telling any of them, “Maybe you should try something else, this isn’t for you”?

No, I’ve never said that because I don’t think I know that. As a teacher, you just don’t know enough, especially if you are only with them for a semester. Someone can write twenty bad stories and then they write a good one; people can potentially develop very fast when they’re young. On top of that, my idea of what’s good or not may be irrelevant—a lot gets published that I don’t like at all.

Also, I was going to mention, the first couple of times I entered the Hopwood, I wrote stories about strippers. I wrote some family stories, too, but with the stripper stories, I think people thought they were nonsense because how could I possibly know what I was talking about? So I began to look at the Hopwood stories that won. I went to the Hopwood room and I saw what they were about. I actually calculated. I thought, these middle-aged judges aren’t going to want to read something from a little girl writing about strippers. The stories that won were about wholesome families, childhood realizations, and moments of truth. I thought, “I can do that.” [Laughter.] What’s funny too is one of my stories about a bunch of strippers was based on an event that actually happened. I kept that one, so I can objectively say it’s bad, artistically it stinks, but the dialogue and events were real. I workshopped this story and everyone thought it was unbelievable, especially the teacher who kept saying he couldn’t believe strippers would say these things or act this way.

When did you first publicly come out to the literary world about the stripping?

Immediately. I was asked to write a biographical statement, and I just included it. And, of course, that was really seized upon. It was probably a little stupid of me.

Do you think your career would have gone differently if you were not so forthcoming?

I think it would have been better if I had not stated it as one of the first things I said about myself when I appeared. I think it would’ve been fine to talk about as time went on. A friend had said to me, “Wait, you can talk about that when you’re fifty.” And I should’ve listened. But in the long run, I don’t think it mattered that much. Now, it’s almost become accepted. But at the time, it was still a bit taboo. Yet I knew so many women and girls who did things like that so I didn’t think it should be this horrific secret.

Are you able to rattle off all of your stories and character names?

No. Well, I haven’t written that much, actually. I’m not that prolific. I can remember all of my stories, but I often don’t remember the point of view or names or what I intended. The things I was thinking when I wrote them are harder to remember.

Do your characters in various stories overlap to you? Are they a few characters voices filling out all of the stories? Do you think that matters?

I think all writers have their themes and characters that one way or another they return to and develop. If you look at Nabokov, how many times does he have an older man and a bewitching young girl? Not in every book, but in many. Look at Bellow’s vulgarity-beleaguered heroes, or Updike’s sexy family men. With Virginia Woolf, many of her books are about this sort of switching of consciousness and taking a very small moment and unraveling it as far as it will go.

It seems fitting to talk about your story “College Town,” which appears in Don’t Cry, since we’re here in Ann Arbor. You originally wrote this story around the time you were writing “Orchid,” which has similar characters and was collected in Because They Wanted To. What was it like to go back and work on “College Town” more than twenty years later? Does writing ever get harder?

Surprisingly easy in that case; I didn’t even have to rewrite it that much. I edited it more than I rewrote it because there was some clunky stuff in there. It was a fairly simple process. However, in answer to the question, does writing ever get harder, yes, it does. It never stops being hard and if you try something you haven’t done before, that likely will be harder than before too, because there’s nothing to fall back on.

Surprisingly easy in that case; I didn’t even have to rewrite it that much. I edited it more than I rewrote it because there was some clunky stuff in there. It was a fairly simple process. However, in answer to the question, does writing ever get harder, yes, it does. It never stops being hard and if you try something you haven’t done before, that likely will be harder than before too, because there’s nothing to fall back on.

In your story “The Agonized Face,” did you feel you were defending anything? What was your intention for the reception of that story? It’s such a complex story.

I was trying to hit as many facets of it that I could. It’s based on an experience I had at a festival in Toronto. The whole thing struck me as so crazy; it was kind of a media bazaar—which was wonderful in a way; God bless Toronto for giving that much media attention to writers—which attached personas to people in a way that was unintentionally grotesque and which then got amplified by people semi-consciously trying to live up to these images. If your persona gets very intensely attached to (ahem) subjects like prostitution and violence, or, say, war, well, those subjects arouse a lot of emotion. About the story, I had no intention for how it would be received because I can’t control that. In terms of myself, I was trying to comically come at it from as many angles as I could.

The feminist author in the story has obviously affected the reporter, in that she made her stop and formulate her own opinions, which cleverly forces the reader to think, “What do I really make of this situation?” Was this a device? Were you intending to get readers thinking about feminist issues?

I never think about provoking thought, but I’m glad if I do. I try not to think about readers because if I do, I get confused. I get out of my own perception in a way. I had a concern about that story, that the narrator sounded too crazy. It turns out people didn’t feel that way about her, and I’m glad. But while feminism was certainly part of it, I was focused on the media madhouse aspect more—how feminism is perceived has to do with that too!

Did you give her a daughter to…

…to make her normal? Yes! Also, having a daughter makes the subjects of prostitution and rape far more loaded for her.

Have you ever received backlash from mothers? Is that another reason you gave this narrator a daughter?

The daughter in the story gives the narrator a kind of grounding, because otherwise she seemed like a disembodied voice. I wanted to give some sense of where she was coming from, and why these things meant so much to her. Otherwise she just seemed like a maniacal talking voice. I would not say I’ve felt a backlash. At times I have felt—this is very vague—but I have felt that women with children sometimes consider me outside the realm of the normal. That they might read me for entertainment, but that they can’t relate to me. I don’t know how true that is, but occasionally I’ve felt it.

How do you carry the influence of alcohol so well through that story and others? Your story “Turgor” also comes to mind.

I’ve been drunk! Part of the thing about making the narrator of “The Agonized Face” drunk, too, was because I was afraid of her sounding nutty. Personally, I can think that way without being drunk, but I thought in this case the reader would cut her more slack for thinking kooky while drunk.

It also generates more empathy for her.

It also generates more empathy for her.

Yeah. Also, she never gets a chance to be out in the world. So she’s a bit out of her comfort zone and thinking out of the box already. Plus feeling a bit defensive. I’ve only once actually written something when I was drunk. Normally, I think it’s a bad idea. You can’t think as clearly. I was at a writing colony, and they are wonderful, but they can also be kind of scary, because you feel like, Okay, I’m here, I’ve got to get work done. I’d gone three days without being able to work and I was getting into a complete panic. So one night after dinner, I drank too much and I stomped back to my cabin and thought, “Goddamnit, I will write!” And actually, it wasn’t bad. I used it in Veronica. The character is kind of drunk, she breaks up with this guy and meets him at the benefit, and he’s there and they go in the bathroom and have sex, and he takes her home in a cab and hands her her underpants.

That’s a good tidbit of knowledge. Another thing you do so well is create these sort of invisible plotlines. Sort of like a good drink. You don’t really taste it until it hits you. So many of the shifts in your stories are internal. For example, Dolores in “College Town” just sits and sorts through rantings and flashbacks. How do you squeeze a plot out of this? Do you do this by keeping the reader wondering, “What will be revealed here that only Mary Gaitskill can reveal at the end of a story?” Sort of like dangling your carrot?

[Laughter.] Well, actually, I don’t like it that I write so much like that. I need to develop a stronger ability to be in the world of action. Interiority is something you cannot do in a film, so it’s a strength for a fiction writer, but I think you can lean on it too much. It works beautifully sometimes, but I think I need to develop an ability to develop action more.

The major shift in “College Town” is that Dolores can’t orgasm in the beginning and then at the end, she can.

That’s big! [Laughter.] Though I wouldn’t say it’s all about that. She’s making peace with the hell in her, integrating her past and present through the daily things she experiences through the people around her. Also integrating how she is privately with how she is publicly, through very quotidian experiences.

Yeah. You’re an expert technician, able to clearly sustain a reader’s attention paragraph to paragraph, line by line, through darting thoughts, time jumps, musings. Has this always come naturally or do you work at that?

It comes naturally and I work at it. The natural part is in how I perceive; the work comes in conveying that non-verbal perception in words. It was difficult in Veronica because there were so many time jumps. It was almost like a palimpsest, rather than flashbacks—it was like one time bleeding through another. Sometimes I changed the time frame by decades in one paragraph or even in one sentence. But mostly, it’s not so difficult. “The Girl on The Plane”: line breaks. In that story, that’s enough to let you know you’ve changed the time frame.

How do you decide which line of dialogue a character will speak or say? They could often be interchanged. Do you switch thoughts and dialogue in revision? Does it come organically as well?

I honestly don’t recall that. I think its usually pretty clear to me, though sometimes I go over and think, “No, that’s enough to keep it as a thought, the character wouldn’t say that.”

I would love to see your characters speak to each other in their intelligent, electric way on the stage. Have you ever written a play?

I tried. I was terrible at it.

Do you have any interest in writing a screenplay?

I don’t think I’m any good at it. Its such a different technique. Yes, I’m good with dialogue, but I also rely very heavily on interiority, and a lot of how I make things happen is by describing things in the room. I did write a screenplay once. I was commissioned to write it. Part of the reason it didn’t work was it wasn’t my idea. I took it because I needed the money, but I thought it was really a screwball idea. It started with a gang rape. It was supposed to be this working-class student at Harvard and an upper-class guy falls for her but he’s embarrassed by his love for her. His evil friend lures her to the frat house and they rape her. This is an early scene. We are supposed to believe she then becomes a famous artist and the gang rape is romantic somehow. And then she takes revenge on them by having sex with them later in life. It was impossible, I thought. The person who wanted it said, “I see it as a combination of The Way We Were and Fatal Attraction!”

Do you think of yourself as a funny writer?

Sometimes, yeah. “The Agonized Face” is definitely a funny story in my mind. So is “Secretary,” actually. Very dark comedy there, but there is an element of comedy.

Do you think of yourself as a funny person?

Sometimes. [Laughter.] If I’m with people I feel relaxed with.

In one of your earlier stories, “Comfort,” the narrator Daniel says, “I always knew there was something wrong with [his girlfriend] Jackie.” How do you allow a reader to see that something seems off about her, but to not be able to identify exactly what? Yet I feel so sorry for her, for both of them. How do you control what the reader thinks of your characters with such command?

Thank you for the compliment, but I’m not trying to control what readers think at all. I don’t think that kind of control is desirable or even possible. People think things about my stories that shock me, and it’s uncomfortable. That is how it is in life—you can’t control people’s reactions and that’s as it should be. But about the characters in “Comfort,” they are both a bit lost and just ill-suited for each other. Yes, there is something stunted about her emotionally, but he’s also not the person she could connect with.

In “Secretary,” Debbie’s boss kind of points out to her that she’s stunted, or emotionally blocked. What’s that process like, creating that block? Sometimes the reader wants the character to act in ways that we know they cannot.

If you workshopped that, people would probably say you need to know more about the male character in that story. He’s like a cipher. He just kind of exists to do things to her. We don’t know where he’s coming from other than he just gets off on doing things to her. For the purposes of that story, I don’t think it’s wrong. It would be interesting to see his point of view, but it would take away some of its power. There’s something about it being all one direction that’s intense, like a big wave. Besides, it’s about her. Part of her experience is she has no idea what’s going on with him. She’s on the receiving end of all of this stuff, which she has no grip on, yet which she finds herself responding to. That’s what makes it a powerful story. And I feel free to say that because it’s one of my favorite stories. And I almost didn’t put that story in the book, by the way.

Good thing you did. Reviewers use the word mentally unstable—

They do? About my characters or about me? [Laughter.]

No, no. About your characters! Do you feel your characters have as many psychological problems as readers seem to think they do? They get a lot of attention for being unstable, bizarre, or weird.

I think most of them are not that weird. I have some characters I’d perhaps describe as mentally ill. I mean, some of them are strange. Dorothy in Two Girls Fat and Thin is a strange person, but her life has been strange. She’s reacting to the circumstances of her life. People are shaped by events, and often what looks strange to an outsider would make a lot of sense if you could see what they were responding to. The family in “Secretary” is a little strange. The father is, anyway, but in a really human way that is both pathetically sad and absurd-funny. Dolores is mentally ill, but not totally, she’s not crazy. She’s in a lot of pain, which, again, is very human. And very absurd, the way she handles it, but also brave.

Just because someone’s different doesn’t mean disturbed.

It doesn’t shock me that people describe my characters that way, although mentally ill is a little strong. In the context of their lives, they’re not that strange. People are strange. The strangeness hits you when you see it written down, but people are weird. Readers sometimes react to something almost too strongly because secretly they know they’re weird. We fail to see the obvious craziness every day, especially if it’s socially sanctioned craziness. Shows like The Bachelor and Want To Marry A Millionaire—OMFG.

You create so much empathy for all of your characters. Can you think of a character you couldn’t create empathy for?

Yeah, I’m sure there are such characters.

If “Secretary” was written by a male, do you think it would be perceived as more entertaining than shocking?

No. I think men are judged more harshly for writing sex scenes.

Really?

Unless things have changed. Do you know a book by Nicholson Baker, The Fermata? It’s about a guy who can stop time. The guy, instead of pursuing world domination or stealing lots of money, he takes women’s clothes off and masturbates on them. He doesn’t rape them and he cleans everything up, and sometimes if he really likes her, if he knows her, he’ll write some porn and leave it where she can find it. Then he’ll come in while she’s reading it, and he’ll stop time again. [Laughter.] I thought it was really funny, but, my God, it got attacked. People just jumped all over him. They thought he was a pervert, a rapist, absolutely filthy. And if a woman had written something this, I think they would’ve been treated much better.

That makes me feel better as a female writer.

[Laughter.] Well, unless it’s changed again. That was back in the nineties. Women are allowed to go places that men won’t be allowed to go. For example, a Japanese writer named Natsuo Kirino, the last scene in her book Out is incredibly violent. I won’t tell you the whole thing, but there is a sex scene in the end, it’s really intense sadomasochism and it’s very romantic. It ends in one of them being killed, but they’re saying, “I love you, I love you.” If a man wrote that, he would be pilloried. He’d be ridden out of a town on a rail. Reviewers were shocked by it, but I didn’t see any condemnation. One British reviewer said, “I don’t dare comment on what I think of this absurd last scene, in deference to the gender of the writer.” Meaning if it was a man, he would’ve clobbered it. And he was making that clear.

I don’t know actually if that should make you feel better though. It is good to have freedom wherever you can, but I think women are allowed more in this case because the body is considered the realm of feminine authority. Also male sexuality is taken more seriously for obvious reasons; a man writing a bloody sadomasochism scene feels more dangerous because men murder women on the regular. Basically, it’s coding what’s allowable in terms of gender on the same traditional criteria. Though somebody like Kirino really pushes it. Most women still seem to fall back on charm and she doesn’t do that for an instant—and good for her.

We were speaking earlier about your profound essay in Harper’s Magazine “On Not Being A Victim.” You undercut Camille Paglia in this essay for stating that if any girl who goes alone into a frat house and proceeds to tank up is cruising for a gang bang, and if she doesn’t know that, then she’s an idiot. We’re on a college campus surrounded by fraternity houses—can you talk some more about your reaction to Camille’s stance?

Hey, let’s not call her by her first name! I think Paglia was saying that girls are more vulnerable and if they are not aware of that and if they don’t act accordingly, they’re stupid. It’s true. Girls are more vulnerable. However, in most cases, you don’t have to walk into a room assuming that if you’re drunk and there are mostly men in the room, you’re going to be raped. It’s just putting it too simply and much too harshly to then be calling people stupid. Its actually not realistic. I mean, sometimes, yes. I remember years ago, I had neighbors. They weren’t rapists, I don’t think. One early evening in summer, I was walking home past their open door and one of them said, “Hey, Mary, come in, we’re having a party.” I looked in. It was all dark, there were no women there, they were all smashed. And I got a bad feeling, so I smiled and said, “No, thanks.” I probably wouldn’t have been raped, but I easily could have been in a situation that was unpleasant. Okay, it could even have turned into rape. But it’s also true that I’ve been in that situation—all guys—and there was no danger. In most cases, you don’t have to walk in assuming that if you’re drunk they’re all going to wind up on top of you.

It’s interesting, I’ve known women who have fantasies about gang rape, and I know they don’t want to be raped—it’s like they want to have some control over the possibility through fantasy. My feeling is it’s not a masochistic fantasy, it’s more like, I can take all of you. I can satisfy all of you and still have more left over. I am powerful. There’s so much in me. With men, I’ve gotten the impression maybe it’s about fear. Because with all of them together, they can take her.

Collectively, yeah.

But I think it’s also about bonding with each other, like having a sexual experience together. Like getting drunk together. Sharing this woman.

When I teach, I see insecurity, pain, and confusion about understanding sex in a lot of young female students here, in their writing. Do you have any advice for these girls?

It seems to have gotten actually worse. I’m not sure if I can speak to girls now because it’s a really different world and it’s been influenced by the proliferation of heavily sexual images, and things that have always been true have gotten more so. For instance, there were always ideals of beauty. When I was young, it was much broader, what was considered attractive. But now it’s very rigid. There’s a certain ideal, and if you’re not it, you’re shit. And almost nobody is it, and even people who are it, don’t feel good enough.

It seems to have gotten actually worse. I’m not sure if I can speak to girls now because it’s a really different world and it’s been influenced by the proliferation of heavily sexual images, and things that have always been true have gotten more so. For instance, there were always ideals of beauty. When I was young, it was much broader, what was considered attractive. But now it’s very rigid. There’s a certain ideal, and if you’re not it, you’re shit. And almost nobody is it, and even people who are it, don’t feel good enough.

It’s not just about appearance either—I meet women in their twenties who are in an absolute panic because they aren’t “successful,” and they have a very high standard of what that is supposed to be—the young women who have expressed this to me have all been more successful than I was at their age. Also, they criticize themselves mercilessly if they haven’t got a boyfriend, and it doesn’t seem to be about being lonely as much as feeling like there must be something wrong with them if they are single. I have been just plain revolted to hear celebrity women publicly worrying that they are the only one in their family to remain unmarried, or that they haven’t got a baby—who expects men to talk this kind of shit?

Women have always been prone to feeling like that, I think, and that isn’t about appearance. Men of course suffer from this stuff too. But it gets heightened when one’s appearance is so relentlessly focused on as an indicator of worth, and that is much, much more extreme now for girls and starting at a younger age. My nieces were obsessed with their looks at the age of seven; I didn’t even know about it when I was seven. I mentioned being a stripper. When I was doing that in the ’70s, only a handful of women who worked that way were really beautiful. They weren’t all tall, thin blondes with breasts of a certain size. There were people who were completely flat-chested, and people who were actually kind of fat. There were women of all shapes and sizes, and some of the most popular ones weren’t even pretty.

But the men were attracted to them.

Yeah. The men liked them anyway because they were open to how the women expressed their sexuality and personality; what they really liked was the feeling that the woman liked them. Whereas now, they all look the same, and they’re all on stage at once, so there’s not so much room for individuality. They’ve all got fake tits, or many of them do. I guess I should admit that my knowledge is limited because I’ve only been in maybe two strip clubs in the last ten years. But in both cases I was really struck by the uniformity, that they were all trying to be the same thing.

It’s a dumb thing to bring up, maybe, because most people aren’t strippers. But compared to what it was like when I was young, it’s just gotten much more rigid what’s expected of young women. Supposedly, they have more opportunities and they’re more equal. Yet they are made to feel worse about themselves. Women are in the army now—big difference, right? Yet there’s a popular TV show on, “Military Wives” or “Army Wives” or whatever—like being a wife is a drama! Can you imagine a show called “Military Husbands,” advertised by a perfectly coiffed young man wistfully staring?

Then there’s the phenomenon of porn being everywhere via the Internet. About a year ago I had a conversation after a story a student had turned in. She was saying that men are not interested in their girlfriends anymore because of porn, and how they expect their girlfriends to be like porn stars. I just couldn’t believe it. I said, “That’s absurd, porn is an act, men want a real response from women.” Well, the cover story in New York Magazine a few weeks ago says I’m wrong, that men are obsessed with and addicted to Internet porn and the way porn stars look and behave to the point that they have trouble responding to real women. The article didn’t say that men actually want their girlfriends to behave like porn stars–in fact, they don’t-but that they almost can’t respond to “real” anymore. Which is a nightmare. I mean, it is New York Magazine, so consider the source. Still, it’s creepy if its half-true.

They can’t get turned on by the live woman in front of them? That’s scary.

And it’s worse for the men, really. It’s like they’re being manipulated to the point where they’ve lost themselves. For the women, though, that is really hideous. If you can’t even be yourself in the most intimate physical way with your boyfriend or husband, that is insecurity on a scale that is going to subvert everything about you.

Do you feel any regret or embarrassment when you look back? With life? With writing?

In my life, yes. But, that’s life. In writing, no. Well, except I do wish I’d written more.

All writers deal with loneliness at some point in their lives. How did you overcome those younger times when you felt bruised inside?

I gradually learned how to be more comfortable in the world. It was harder than I can describe. But eventually I learned to be a better friend to myself.

What types of female characters would you like to see more of in the future?

Never thought about it. I’m not sure I could define it. I do hope that women become better, but I don’t know if I could say particular qualities they need to have in order to do that. Except that they need to forget about being charming or pretty on the page. Charm and prettiness are irrelevant in art and in heavy doses they are deadly.

Do you think there’s a male equivalent to Mary Gaitskill writing right now?

Do you think there’s a male equivalent to Mary Gaitskill writing right now?

That’s an interesting thought. If there was, I might not have read him, but I don’t know how you would make that comparison.

One of our professors here, Nicholas Delbanco, gave a reading and talk last week from his new book, Lastingness, about artists producing work in the face of aging. What do you think if you think of mortality?

Well, I do think about lastingness. I think I have a good shot to last for maybe fifty years or something like that. Lasting longer than that, I’m not sure. I would like to. Especially because I don’t have children, I like the idea of being part of a group of writers that leaves something behind. I know how meaningful it was to me when I was young to read, oh gosh, not even writers I consider that great now, but Colette, say—she was one of the first literary writers I loved and really responded to. D.H. Lawrence was another one. Flannery O’Connor, too, whom I consider great. It was the most amazing thing to be that young and living in such a different world and yet to be reading people describing a life that was so different from mine, but which I could still respond to.

A way to propel yourself into the future.

And to connect with the past and to feel a continuum. If I could do that for people—and I do mean people, not just women—that would be a justification for my existence. I think there’s real beauty and hope in that. My fear is that it just won’t matter anymore, or that people won’t read, or that the world will actually be destroyed, or that I just won’t last that long. But even fifty years is pretty good.

How does it feel to be so successful?

I don’t consider I am that successful. I’m grateful for what I have. I have a degree of success and I’m happy about it, but I think I could do better.

And what’s next?

I’m working on a couple of novels now. They are both hard.

One last simple question: Do you feel you’ve affected women?

Yes. [Smiling.]

Further Links and Resources:

- Read some of Gaitskill’s work online:

- “The Other Place” in The New Yorker

- “Something Better Than This” in Fictionaut

- Read Gaitskill’s essay “On Not Being A Victim” in Harper’s Magazine (unfortunately, for Harper’s subscribers only)