Bret Anthony Johnston is known for his visceral narratives set in his home near Corpus Christi, Texas. Weather, place, and storm events reflect the emotional lives of his characters, lives that are raw and vulnerable and exposed. This window into the intimate underpinnings of his characters’ hopes and longings makes his debut novel, Remember Me Like This (Random House), which came out in May, impossible to put down.

The novel explores the nature of love and forgiveness when a kidnapped son is returned home. Remember Me Like This is haunting and beautifully written as it renders a family’s expectations and heartbreak in the aftermath of a devastating crime. What’s captivating about this novel is that Johnston doesn’t focus on the sensational aspects of what happened to Justin during his abduction. He focuses on the aftermath and the struggles of the family once Justin is returned. Deep rifts in the family and the wounds they carry as a result of the boy’s kidnapping could tear them apart, but as the summer heat flares and storms begin in the Gulf, the family fights to find the ties that keep them together.

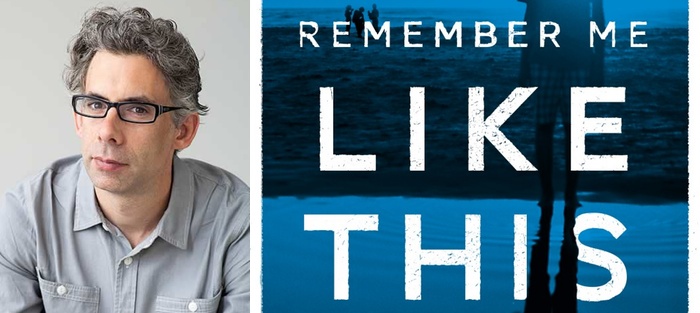

Bret talked with me via email from Cambridge, where he is the Director of Creative Writing at Harvard University. He is also the author of the award-winning Corpus Christi: Stories (Random House, 2004) and the editor of Naming the World and Other Exercises for the Creative Writer (Random House, 2008). His work appears in The Atlantic Monthly, Esquire, The Paris Review, Glimmer Train Stories, Virginia Quarterly Review, The Best American Short Stories, and elsewhere. He is the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships, and happens to be the nicest guy you’ll ever meet. He’s brimming with intensity behind a laid back, welcoming manner that he brought to this thoughtful interview.

Interview:

Sarah Anne Johnson: How did you get started writing and how have you worked to develop your craft?

Bret Anthony Johnston: Like so many writers, maybe every writer, I started writing because I loved reading. I love language. I love words and sentences. It’s also true to say that I’ve always loved story, regardless of medium. Television, movies, gossip, anecdotes, plays—if the thing purports to be a narrative, chances are that I’ll love it. And yet I started out writing poetry, which was excruciatingly bad. This was in high school, I think, and although the poems themselves were garbage, I fell in love with how a person could work with language, how you could make something solid out of it. From there, I moved to writing stories—which were themselves garbage for a long, long time—and I felt more at home.

To develop my craft, I read and read and read. I went to graduate school twice to study writing [Miami University (Ohio) and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop], and I just worked to understand how stories were built. My approach to craft has always been pretty blue collar. I don’t go in for stuff like inspiration or the muse, but rather I’d look at how stories I loved were put together. I’d take them apart and set them right again just as I would do with a motorcycle engine if I wanted to be a mechanic. I benefitted from a number of tremendous teachers, and countless smart peers, and through it all, I apprenticed myself to literature I loved. I’m still doing that today.

How did your blue-collar approach to writing stories help you write your novel? What were the unique challenges in shifting from writing stories to a novel?

Actually, I’ve come to look at this subject from the opposite direction. I’m not all convinced that knowing how to write short stories prepares you to write a novel; however, I’m almost positive that writing a novel will teach you a lot of what you need to know to write short stories. My students always think they need to get a handle on writing stories before they graduate to a novel, but I’ve seen little evidence to support the logic. The scale of a novel, though, will throw a light on what it takes to write stories. You get a sense of the possibilities available to the shorter form. You see how much latitude you have, and you can glean where to take risks and where to play it safe. If I thought I could get away with it, I would require all of my students to draft a novel to prepare them to write stories.

I should also say that I don’t believe that writing novels is any more difficult than writing stories. Stories, in fact, are probably harder. What novels require that stories typically don’t is a substantial commitment of time and energy. You have to choose material, you have to find characters and a world, that will sustain your attention for a very long time. What will sustain and reward your curiosity for a number of years? That’s the most difficult thing about writing a novel. Beyond that, you merely have to show up for work every day.

Your book of writing exercises, Naming the World, provides a master class in developing fiction. How did putting this book together impact your own writing?

I completed every exercise that was submitted to the book, and when I assign them to students, I tend to do them again. I’m proud of how well the book has held up, and I’m humbled by how many writers have found something useful in the pages. The book has also impacted my reading in two ways: one way is that when I read contributors’ fiction, I sometimes notice how their exercises grew out of their own work, their own creative tendencies. Another way the book has impacted my reading is that a number of writers have sent me their published stories and books that came from the exercises in Naming the World. The idea that the anthology is spawning work that goes onto find its own readership is entirely gratifying.

I completed every exercise that was submitted to the book, and when I assign them to students, I tend to do them again. I’m proud of how well the book has held up, and I’m humbled by how many writers have found something useful in the pages. The book has also impacted my reading in two ways: one way is that when I read contributors’ fiction, I sometimes notice how their exercises grew out of their own work, their own creative tendencies. Another way the book has impacted my reading is that a number of writers have sent me their published stories and books that came from the exercises in Naming the World. The idea that the anthology is spawning work that goes onto find its own readership is entirely gratifying.

Remember Me Like This narrates the story of a family contending with the aftermath of their son’s kidnapping once he is returned to them four years after the fact. Where did you get the idea for this story and what drew you to this unique emotional terrain?

I’m interested in aftermath and I’m interested in the places where we take shelter, especially when the shelter starts to shake in the storm, starts to collapse. I’m intrigued by the methods of emotional survival and the methods’ limitations.

The novel started with a decades’ long curiosity about who would volunteer for overnights shifts to rehabilitate a sick dolphin. I’d volunteered for that kind of work when I was younger, and I’d always heard that the overnight shifts were the toughest to staff, but when I looked at the schedule they were always full. I’d wondered about who was doing those shifts ever since, and gradually the character of Laura Campbell crystallized. I started writing after I realized that it would be her son’s breath, not her own, inside the inflatable alligator she brings for the dolphin.

You inhabit the characters of a mother, her two sons, and their father. How did you inhabit these specific psychological states?

Revision. Laboring for years to surrender the story to the characters, to make sure the actions on the page were theirs, not mine.

I also intuitively gave myself a similar exercise that I only recognized in retrospect. The exercise was to render a number of different characters responding in different ways to the same event—in this case, Justin Campbell’s return. The way a mother responds to her missing son is utterly different from the way his young brother does. I worked to excavate the characters, to mine their hearts and histories for the most revelatory reactions. How would a woman who works at a dry cleaning plant relate to her missing son’s unwashed clothes? How would a father who’s worked his whole life to save for two college tuitions face a future where he was only obligated to pay for one? How would a younger brother view his parents in light of their eldest son’s disappearance? I wrote the novel to find out the answers. I knew each of the characters would focus on different aspects of Justin and his return, so I wasn’t surprised by where they chose to train their attention, by where they chose to look. I was, though, consistently surprised by what they saw.

Are there challenges to writing a woman character that you don’t find in writing male characters?

Are there challenges to writing a woman character that you don’t find in writing male characters?

I find every part of writing impossibly challenging. Nothing about it is easy, and every sentence requires you to start from scratch again. Each story is a kind of on-the-job training because what you’ve done in the past proves useless in the face of what’s on the horizon. That said, I don’t find female characters any more challenging to write than male characters, just as I don’t find adult characters any more challenging than young characters. They all require an unimaginable amount of work, patience, stubbornness, and humility, but none of them require more than another.

You create a sense of suspense from the very beginning of the novel. I’m sure it took a lot of work and patience to figure out what to reveal and what to hold back in order to keep the reader turning pages?

To my mind, one of the jobs of a novelist is to make a reader want something and then make them wait for it. There’s an element of seduction here: the longer they wait, the more they want it. As a reader, I really appreciate plot. I appreciate suspense and consequence, and as I mentioned earlier, I crave surprise. Most of the surprises in the plot were surprises to me in the first draft. Honestly, I thought the book would end differently. I wrote toward a different ending for hundreds of pages until the current ending, the real ending, made itself known. Once it did, I spent the next few drafts cultivating that surprise, preparing the reader in ways that are, I hope, clear. If anyone cares to read the book a second time, I suspect they’ll see that the end was clear at the beginning.

Practically speaking, while I was writing the novel, I had a huge bulletin board in my office so that I could keep track of what had happened in each chapter, who knew what when, and when we last saw a given character. The board wasn’t quite as crazy looking as the kind you see in movies that deal with CIA agents and serial killers—interesting that their boards always look so similar, no?—but it was getting close. The notes were color-coded. Each POV character had his or her own color, so I could look at the board and see that we needed more red in a certain chapter, which meant we needed more Griff.

As in Corpus Christi: Stories, weather plays a large role in Remember Me Like This, as if it’s a character unto itself. Can you describe the impact of weather on the lives of your characters and on the tone of your narrative?

If the story is set on the Gulf Coast of Texas, there will be storms in the summer and oppressive heat. That said, I never planned for a tropical storm to have any impact on the characters in the novel, but they had gone through most of the summer without any rain, so something was bound to come ashore. When it did, their actions and reactions were blessedly unintended.

If the story is set on the Gulf Coast of Texas, there will be storms in the summer and oppressive heat. That said, I never planned for a tropical storm to have any impact on the characters in the novel, but they had gone through most of the summer without any rain, so something was bound to come ashore. When it did, their actions and reactions were blessedly unintended.

I did, though, know that the heat would be another kind of pressure that weighed on the characters. I knew the humidity, the film it leaves on your skin and every surface, would be inescapable much like their fear, grief, and loss. The heat is unrelenting and the methods for coping with it—fans, air-conditioning, the beach—are relatively futile and fleeting. This felt like an opportunity, a way to further strip them of shelter. I wanted to exact as much pressure on the characters as possible to find out who they most deeply and essentially were, and as such, I never missed an opportunity to turn up the heat.

Like weather, place also shapes the lives of the characters in Remember Me Like This. The small town of Southport brings people together in the search for Justin and their joy at his return. Can you talk about the role of place in the novel?

For me, setting in fiction is something of a mandate. I’m interested in stories that could only happen in a specific place. With the novel, the place became another source of pressure. If the story had taken place in a large city, or a place with a more temperate climate, then I don’t know that the characters would have faced the same kind of conflict. There would have been more places to hide, to seek solace. I also liked the idea of the family living on a spit of land surrounded by water, a locale that you reach via bridges and ferries; such isolation made sense for the Campbells. This wasn’t planned at all, but cultivated once I started to notice that their geographic location mirrored their emotional state. Likewise, the deeper I got into the book, the more it made sense to me that they would live in a place that appears desirable until you look closer, until you’ve lived there.

Griff is a dedicated skateboarder. You are a serious skateboarder yourself. Why did you give this attribute to Griff?

Skateboarding is a solitary activity. Unlike more conventional sports like football and baseball, both of which are, of course, huge in Texas, there aren’t teams in skateboarding. You’re alone. No one can help you ride away from a trick, just as no one can save you from falling. These attributes resonated with me for Griff. Given the choice between spending his days at the beach or at a sketchy, half-demolished motel with an empty pool, I knew he’d choose the latter. I knew he’d avoid the crowds of smiling families. I knew he’d feel more at home in a place where most everything had been destroyed.

Skaters, especially in small towns in Texas, are often looked at with suspicion and derision. They’re outcasts who live beyond the margins of conventional society, and they’re viewed as having little in common with most everyone else. Again, this seemed true and viable to me—and not just for Griff, but for his whole family. After Justin disappears, the family no longer fits in, and they’re cast out of society because their friends and neighbors can’t fit them into a comfortable box anymore. In Griff’s case, this is made manifest with his skateboarding. It’s his stigma and his solace.

And, of course, it’s his connection to his brother. For the years that Justin was gone, Griff threw himself into skateboarding as a way of feeling close to his brother. He obsesses over tricks and perfects them with the hope of one day impressing Justin who used to be his idol on the board. Griff believed that Justin was somewhere in the world doing the same thing, thought it was a kind of bond and language tethering them together, so when he finds out otherwise, he feels all the more unmoored. There is, I hope, something of a similar pivot for each of the members of the family: as soon as Justin is found, they feel more and more lost.

As an aside, do writing and skateboarding have anything in common for you?

How much time do you have? I can hold forth on this for days, if not weeks. To my mind, the similarities are profound and boundless. Some of it has to do with the solitary nature of writing and skateboarding, how everything rests on your shoulders and yours alone. The way you become a better writer is the same way you become a better skater: you log hours and hours and hours. (Incidentally, it seems to be the same thing with becoming a great magician. I love this quote from Teller, of Penn and Teller: “Magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect.”) And skating, like writing, requires an unimaginable persistence, an almost inhuman resilience. You learn to expect failure. You learn to embrace it. You learn how to trust the process, how to push forward through pain and disappointment and frustration. You learn how to get back up. I’ve seen some incredibly talented writers fall down and stay down. It’s never made sense to me.

On a slightly more esoteric level, I see similarities in the language we use to talk about skating and writing. When you’re learning a new trick, you’ll say something along the lines of “I haven’t made it yet, but I’m close.” Or: “I made it once.” Or: “I can make those.” And what are we as writers except people who make stories, people who make art. Both skaters and artists are in the business of creation, of making things that didn’t exist before that moment in time. I love the idea of tricks having been “made” and existing in the world in the same way books do. That the tricks lack the physical artifact that books enjoy doesn’t matter to me or make them feel any more ephemeral. What matters is that they were made, that someone put in the work of creation.

You write about sexual abuse in this novel without sensationalizing it or graphically portraying it, but rather implying abuse and portraying the emotional repercussions on Justin and his family members. How did you navigate this difficult terrain?

There are a lot of answers to this question, but I think the truest is that I wanted to respect Justin’s privacy. Just because everyone wants to know what he’s endured—the authorities, his family, the reader—doesn’t obligate him to disclosing it. There are allusions to the abuse he endured, of course, but to delve any deeper seemed unnecessary to me. We’ve all seen that story before, far too many times, so we have the unfortunate ability to fill in those blanks. Some readers have suggested that I left out the details of the abuse to intensify the effect, to let people’s imaginations come up with a more terrifying and punishing version of events than anything that could’ve been rendered on the page. This isn’t true. I left those parts out because Justin wasn’t ready to talk about them. I deferred to him. He’s been through enough.

How do you find the ending of a novel?

It sounds uncomfortably pithy, but I think you find the end of the novel by paying attention to how it begins. The same is true for short stories. You pay attention to where the characters have been, where they’ve spent their time and energy and emotion. You take stock—what Ron Carlson calls “inventory”—of what’s been used to create the narrative, and you coax surprise from those elements. Where writers get into trouble, I think, is by forcing a novel or story to end the way they want it to end, not the way it should end. You cleave too tightly to that idea, to that intention, and the ending can feel unearned or suffocating. I don’t like ambiguity in stories, but my favorite endings are those that open up the narrative. There’s a release rather than a tying off. A silly way to think about it is to imagine a dog following a scent. The scent only leads to one place, so as long as the dog stays on the trail, she’ll find the true ending. The same is true for writers. If you recognize that you have the wrong ending, if you feel the impulse to convince yourself that it’s the right ending and you know that you’re the last person who should need convincing, then double back and pick up the sent again. Go back to the beginning and follow the trail the characters have left for you. If you follow the characters’ path, they’ll deliver you to the right ending because it’s the one of their making, not yours. Your job is to follow, not lead. If you can surrender control, if you can trust the characters rather than doubting them, if you can feel more than think, then you’ll find the right ending.

It sounds uncomfortably pithy, but I think you find the end of the novel by paying attention to how it begins. The same is true for short stories. You pay attention to where the characters have been, where they’ve spent their time and energy and emotion. You take stock—what Ron Carlson calls “inventory”—of what’s been used to create the narrative, and you coax surprise from those elements. Where writers get into trouble, I think, is by forcing a novel or story to end the way they want it to end, not the way it should end. You cleave too tightly to that idea, to that intention, and the ending can feel unearned or suffocating. I don’t like ambiguity in stories, but my favorite endings are those that open up the narrative. There’s a release rather than a tying off. A silly way to think about it is to imagine a dog following a scent. The scent only leads to one place, so as long as the dog stays on the trail, she’ll find the true ending. The same is true for writers. If you recognize that you have the wrong ending, if you feel the impulse to convince yourself that it’s the right ending and you know that you’re the last person who should need convincing, then double back and pick up the sent again. Go back to the beginning and follow the trail the characters have left for you. If you follow the characters’ path, they’ll deliver you to the right ending because it’s the one of their making, not yours. Your job is to follow, not lead. If you can surrender control, if you can trust the characters rather than doubting them, if you can feel more than think, then you’ll find the right ending.

What are you working on now?

I’m finishing a collection of short stories and taking preliminary steps toward my next novel. There are also a couple of film and television projects being tossed around, and I have a list of skateboarding tricks I’d like to ride away from this year. I’m in a fortunate and exciting place, and I feel an immense gratitude toward this work that is so beautifully difficult.