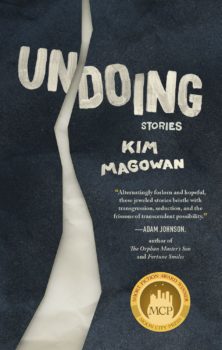

I met Kim Magowan in late 2014 after we both entered the Sixfold fiction contest. If you don’t know it, it’s a contest in which the winners are selected by the writers who have entered in their work. Stories are submitted anonymously, and voting takes place over three rounds, each writer randomly assigned six stories per round. Kim was assigned my story during one of those rounds. She was one of the few readers who left me detailed feedback, and her comments were insightful and generous. If you’ve never submitted to Sixfold, let me tell you, this is a rarity. Somehow, despite all the voters who said things like—I kid you not—that they wished the protagonist of my story would drive off a cliff and die, I ended up winning that contest. I emailed Kim afterward to take her up on reading an edited version of the story. We immediately hit it off, and we’ve been sending each other our drafts ever since. Since July of 2017 we’ve been collaborating on a series of short stories as well.

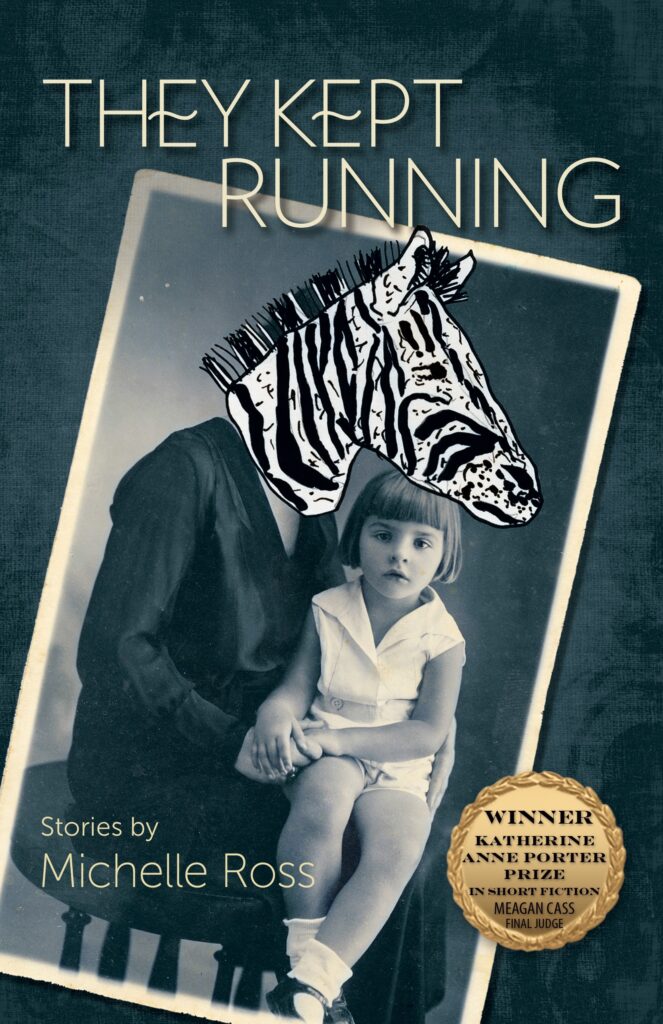

Kim’s debut book, Undoing, is the winner of the 2017 Moon City Press Short Fiction Award. Stories in this collection have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Hobart, Indiana Review, Moon City Review, New World Writing, and many other venues. These 29 stories vary in length and style and tone, but one thing they all share is that they’re composed of exquisite sentences. Kim’s prose is so sharp and elegant that it really doesn’t matter what she writes about—I’ll keep reading for the prose alone. And also for the humor. Kim’s writing is often quite funny.

Kim’s debut novel, The Light Source, is also forthcoming, in 2019 from 7.13 Books.

She lives in San Francisco, where she teaches in the Department of Literatures and Languages at Mills College.

Interview:

Michelle Ross: Kim, I want to begin by asking you about your path to becoming a writer. You didn’t go to graduate school for writing. Instead, you got your Ph.D. in English literature. Also, you’re publishing your first book a little later in life, after having two kids, who are now in their tweens (or almost). What was your path to becoming a fiction writer like? Have you long written fiction? Was there a point when you decided to take your writing more seriously?

Kim Magowan: When in college, I was very conflicted about whether I should get an MFA or a Ph.D. I loved both—writing literary criticism and writing stories—and they seemed disconnected to me, requiring different parts of my brain. I got the Ph.D., and I’ve never regretted the choice. I love teaching. But it did mean my fiction writing was, for years, shoved to the side. My great uncle James Merrill warned me that getting a Ph.D. would be terrible for my creative writing, but it wasn’t (I don’t think, anyway) for the reasons Jimmy forecast—the infiltration of jargon, convolution, and self-consciousness. Rather, creative writing became a “hobby” instead of “work.” Plus, I compared my writing to the great (capital G) writers I was thinking about and teaching. Of course my fiction shriveled in relation to, say, Faulkner’s or Woolf’s.

I continued writing on the side. There are a couple of stories in my collection that I wrote first drafts of in my twenties, and two chapters of my novel date from then as well. But I hardly ever sent stories out, I was so paralyzed by fear of rejection and the conviction that my writing was imperfect (of course it was, and is, imperfect). Then I had a demanding job, and small kids, and I had time to do two things reasonably well (teaching and parenting), but not three. It wasn’t until I was forty-three, and my daughters were both in school, that I had time on my hands, and for the first time in twenty years I seriously devoted myself to writing. I also began submitting stories to journals. The rejection was challenging—I’ve never been good at rejection—but I’ve gotten much better at shrugging it off, recognizing that writing is subjective, journals receive more publishable material than they have room to print (I certainly confirm this suspicion now that I am a fiction editor), and not taking it personally. I’ve gotten better, in other words, at writing to please myself.

I continued writing on the side. There are a couple of stories in my collection that I wrote first drafts of in my twenties, and two chapters of my novel date from then as well. But I hardly ever sent stories out, I was so paralyzed by fear of rejection and the conviction that my writing was imperfect (of course it was, and is, imperfect). Then I had a demanding job, and small kids, and I had time to do two things reasonably well (teaching and parenting), but not three. It wasn’t until I was forty-three, and my daughters were both in school, that I had time on my hands, and for the first time in twenty years I seriously devoted myself to writing. I also began submitting stories to journals. The rejection was challenging—I’ve never been good at rejection—but I’ve gotten much better at shrugging it off, recognizing that writing is subjective, journals receive more publishable material than they have room to print (I certainly confirm this suspicion now that I am a fiction editor), and not taking it personally. I’ve gotten better, in other words, at writing to please myself.

How do you think teaching literature has affected your writing?

The best way to improve one’s writing is to read good literature, and because of my job, I have a leg up on that. I don’t think the writers I teach have influenced my style particularly; I don’t imagine most people would read one of my stories and guess which writers I specialize in. But my job has no doubt affected my writing. There are a lot of teachers in my stories, which embarrasses me—I wish I was more imaginative like you, that my characters had exotic, bizarre jobs like taxidermists and dominatrices! I also have an etymology tic that my students are all (eye-rollingly) familiar with—I love the roots of words—and often in one of my stories there’s some “want to know what this word means?” moment. Kind of like with you with the interesting factoids about science—it’s hard to keep our jobs from smearing themselves onto our fiction.

Chris James, editor of Jellyfish Review, recently noted that there are “more perfect moments in one Kim Magowan story than many writers get in an opus.” Having read everything you’ve published, including earlyish drafts of stories these past three years, and now collaborating with you over the last seven months, I’m inclined to agree. My feeling often is that writing gorgeous sentences is easy for you; you seem so natural at it. Of course, I know that sometimes the things we appear to others to be naturally good at are things on which we work very hard. What’s your perception of what comes easy for you as a writer and what’s more challenging for you? How do you deal with the challenges?

Chris is so supportive and enthusiastic! I love him. Well, the truth is I’ve always felt confident about my writing on a sentence level—smooth prose isn’t hard for me. Remember when we were working on “How Things Work in Your Home” and my assignment was, “Make it prettier”? What is difficult for me is plot (kind of a huge component for a writer to find challenging!). This is actually the one Venn diagram overlap between my fiction-writing self and my criticism-writing self: I was always, as a scholar, much better at elegant close readings than big-picture arguments. I’m also a baby about revision. I hate revising. It’s funny, because revision is the part of writing my partner finds most satisfying—that’s where Bryan feels like he gets the marble statue from the block. The fun part of writing for me is the inspiration and initial outpouring; the painful part is spending five hours (as I sometimes did with my novel) paring away 250 words. It’s like sticking pins in my eyes. What has made that process easier for me in the last several years, quite frankly, is you. I write a draft, I send it to you, you give me edits, I take most of them, voila: it’s done. You’ve shrunk the blood, sweat, and tears of writing for me exponentially! Also, I suck at titles (which no doubt would amuse my students, since I insist that they have good titles on everything. But naturally, we teach to our defects).

What makes a short story great in your opinion?

That’s a wonderful, difficult question. I suppose, thinking about my favorite stories, they have to do a couple of things. They have to honor the genre, which means they need to be lean and mean. There needs to be no fat on the story, nothing extraneous. And that has nothing to do with the length of the story—Alice Munro is probably my favorite living short story writer in English, and her stories tend to be long. I’m not advocating minimalism here. It’s more nebulous and fuzzy: no unnecessary bits. The second thing (and I know this sounds at odds with the first) is that a great short story should feel like a novel: it should have the same gravitas and emotional power. There is nothing slight or trivial about a great story. The fact is, it’s the harder form to pull off—novels are more forgiving of defects—which is why I am baffled by the way agents, publishers, and some prestigious awards (like the Man Booker, which refuses to consider short story collections) treat short stories like a lesser form.

What are some of your favorite short stories, stories you think every aspiring fiction writer should read? Stories you’ve read over and over again?

Another excellent question, hard to answer. I want you to give me a magic number so I know when to stop; I want some rules about classic versus contemporary. But fair enough: stories I’ve read over and over again is a pretty apt measure, and I’ll name eleven, because that’s my lucky number. “The Dead” (James Joyce), “Dark Meadow” (Adam Johnson), “A Temporary Matter” (Jhumpa Lahiri), “Everything That Rises Must Converge” (Flannery O’Connor), “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” (Alice Munro), “Benito Cereno” (Herman Melville), “The American Embassy” (Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie), “The Isabel Fish” (Julie Orringer), “Mothership” (Eric Puchner), “The Semplica Girl Diaries” (George Saunders), “People Like That Are The Only People Here: Canonical Babbling in Peed Onk” (Lorrie Moore).

Undoing is a mix of both longer stories and flash fiction. Could you talk about the differences and/or similarities in writing longer stories and flash fiction? Do you have a feeling when you begin a new story that it will be short or long or does that come later?

I started writing flash for a very pragmatic reason: it’s the only kind of writing I can reliably get done when the semester is on. I can crank out a first draft of a flash story in a sitting, and revise at leisure. Flash fiction is the closest prose comes to poetry. If a novel is a big bucket of sea water, flash is the salt when all the water has evaporated out. I love the form: it’s so disciplined, you punch and you run. Sometimes I have a keyword in mind when I’m composing a flash. For “Dragon,” the keyword was degradation; for “Mrs. White in the Ballroom with the Lead Pipe,” the keyword was blow (as in, psychological blow, but also, blow to the head). Sometimes I know a story will be a flash piece from the get-go, like “Subject: Lay Off the Lays”: conceptually, that needed to be tight. Sometimes, as with “Daisy Chain,” I think I’m writing a longer story, and then I come to a point that I know is the ending, and I read it over and realize all the necessary bits are there. Longer stories, as you and I have discussed, are much more unwieldy, harder to pick up again, harder to pace, harder to sequence.

If you had to make a list of about ten words to represent what Undoing is about, what words would you choose?

- Disillusionment

- Games

- Addiction

- Desire

- Sabotage

- Nostalgia

- Connection

- Naming

- Regret

- Myth

Perfect list. Would you tell us a bit about the making of your collection? How long have you been writing this book? What were the challenges of putting stories together for a collection?

There are three or four stories in that collection that I first drafted ages ago. The oldest one I wrote when I was twenty (of course I’ve revised it a lot since). The majority of them, though, are from the last six years, when I seriously buckled down to writing. When you and I first met, three years ago, and exchanged manuscripts, my collection was less than half the size, so you’ve read first drafts of most of these stories. The toughest thing about putting together the story collection was getting the sequence right—you and I had many conversations about sequence, with both of our books. My thorniest issue was that I had two sets of linked stories, and I needed to figure out whether to lump them together (like Jhumpa Lahiri does in The Unaccustomed Earth) or pull them apart. So that was a headache. The great benefit of writing a short story collection is that it’s easier to fix than a novel. If I had my doubts about a particular story, I pulled it out. With a novel, removing a piece means toppling a Jenga tower.

Is there a story or stories in Undoing that you’re either most proud of or most fond of? Why?

That’s such a Sophie’s Choice question! They are all my babies. I feel guilty, like they’re listening from around the corner. Among the very short ones, I’m most proud of “Squirrel Beach.” I felt like it did everything I wanted it to do, and it was the first time I stuck up for an ending. I like “Family Games” a lot. That story landed in my lap: I had entered another story in the Sixfold contest that I had to withdraw because it was accepted elsewhere, so I had to come up with something new within three days. I stayed up all night writing “Family Games.” I am also attached to my linked stories, the Ben and Miriam ones (“Brining,” “This Much”) and the ones about Laurel (“Eleanor of Aquitaine,” “Warmer, Colder,” “On Air,” “Pop Goes the Weasel”). My writing group of the time really didn’t like one of the Laurel stories—they found “Warmer, Colder” disturbing. I remember you talking me off the ledge about that story, convincing me that it was not only worth including, but one of my best.

Both your daughters have been doing some fiction writing of their own. Do you offer them any advice? Have you learned anything from reading their writing or observing their processes?

Yes, we’re a family of writers! Nora told me she emailed you for some revision advice for one of her stories (because Michelle Ross is the story-whisperer in these parts). Both of them, I have to say “objectively,” are talented writers. Nora published her first story (in The Telling Room) when she was eleven (it only took her mother thirty-three years!). With my older daughter, we talk about the importance of revision—going through her draft and refining the clunky parts, cutting the fat. She always wants to use fancy words, so we talk about the importance of the right word (Flaubert’s le mot juste). My little girl has been working on a gothic novel called Ms. Granick about a teacher who may or may not be a vampire, and the four intrepid little girls who devise traps to unmask her (involving holy water and garlic bread). This was inspired by campfire stories our friend Jennifer told her, and Camille has been writing it for at least two years. For some unaccountable reason it’s set in London. What my daughters remind me of, most importantly, is that writing is supposed to be fun. Camille is always begging to use my computer so she can write. That’s useful for me to observe, when writing feels particularly hellish or arduous.