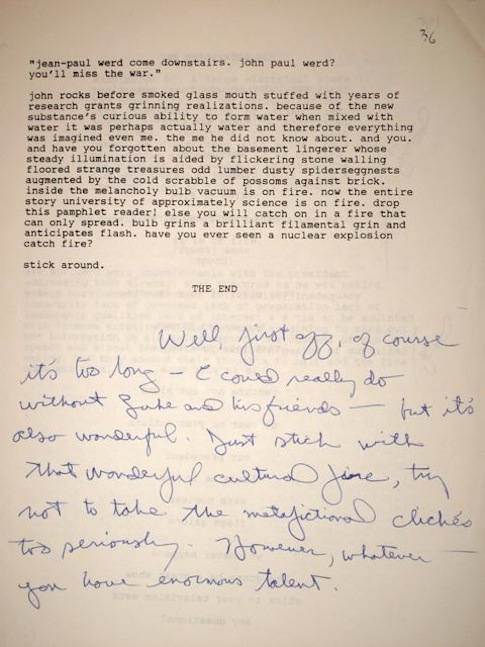

In 1990, William Gillespie was a student in one of my introductory fiction writing workshops at the University of Illinois. In beginning classes I sometimes find it difficult to nurture my students’ ambitions into stories that will fill six pages, but for William that was not a problem—for one assignment he turned in a 36-page single-spaced story. A brilliant story. (Click on image below to see comments.)

In the years since then, William went on to study under and impress a stellar cast of mentors: David Foster Wallace, Robert Coover, and Lucia Cordell Getsi. He was granted one of the first MFAs in Electronic Writing, from Brown University, and he established his own cutting edge press, Spineless Books. Until recently, he was most known as the co-author of the world’s longest literary palindrome, and an award-winning hypertext novel. William ‘s new (print) novel, Keyhole Factory, has just arrived with a fanfare of justly deserved advance praise, with Publisher’s Weekly declaring, “you would have to go back to Denis Johnson’s Fiskadoro to find such a purely poetic take on the unthinkable,” and Booklist calling the novel, “a violent, apocalyptic story told with an arsenal of narrative tropes,” while John Warner at Inside Higher Ed gushes, “one of the most absorbing and inventive books I’ve read in the last year.”

Somehow, during the busy month of his publication date and the birth of his first child, William and I managed to maintain an ongoing conversation about his work.

Interview:

Keyhole Factory cake from launch party, 13 November 2012

Philip Graham: Your novel arrives with a couple of intriguing extras, which can be found on the web. The one I’d like to talk about first is the elegantly convoluted map following a timeline from 2009 to 2015, linking the drumroll of chapters with the appearances of the various characters via a daunting web of sinuous colored lines. I know this is influenced by the mind-warping narrative strategies of the pulp writer Harry Stephen Keeler, who wrote novels with titles like The Skull of the Waltzing Clown and Scarlet Mummy. You’re a big fan, and wrote an essay on Keeler for Ninth Letter way back in 2004. Could you elaborate?

William Gllespie: In 1926, deranged fiction pioneer Harry Stephen Keeler authored a series of magazine articles about his methods: The Mechanics and Kinematics of Web-Work Plot Construction. As I wrote for Ninth Letter, Keeler’s stylistic indulgences make his complicated treatise unnecessarily impenetrable and strangely organized, but his ideas are, I maintain, unique, internally consistent, and genuinely useful. Keeler’s idea of a beautiful novel resided in the complexity of its plot, and he followed highly specific rules to make his plots elaborate and yet, to his mind, structurally sound. His novels’ pre-compositions were not outlines, but sprawling web-work maps of intersecting characters resembling, more than anything, wiring diagrams.

At first, your complicated map worried me about what I was getting into, before I read the first page. But what I love about your book is the clarity and flow of your prose. It’s a pleasure to read, with the characters carefully rendered. Experimental fiction with a human face.

In addition to my fascination with form and structure, I want to respect that mysterious property of good stories that makes you want to turn the page to see what comes next. There are myriad established and undiscovered Oulipian, narrative, and typographic forms one can deploy for the sake of linguistic acrobatics, but for me the challenge is to craft an unusual literary form that is relevant, and even natural, for the story it tells—a form that amplifies rather than obscures its content.

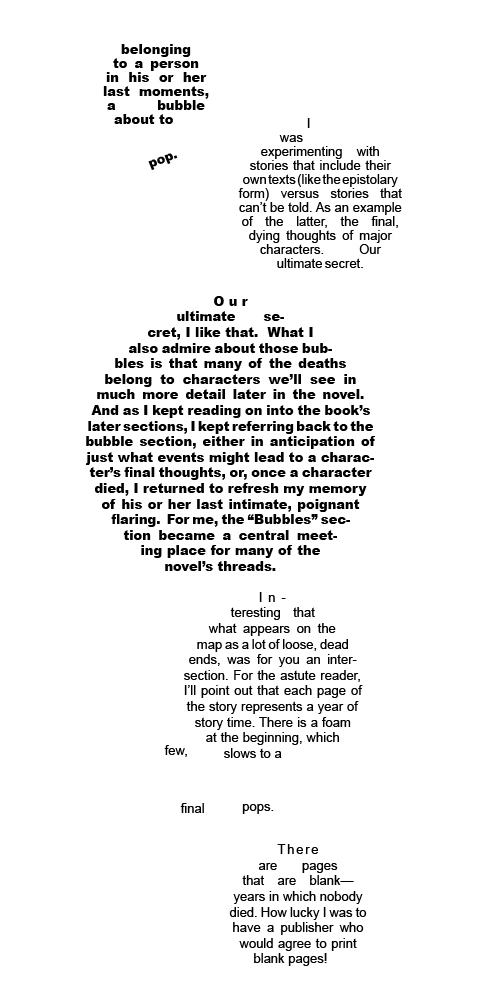

Speaking of form amplifying content, many sections of Keyhole Factory play fast and loose with the usual strait-laced configurations of traditional typography. The section “Bubbles,” for instance, is a series of voices, each voice a floating circle of text, each voice

I really admire how the typographical inventiveness of Keyhole Factory never seems like a grandstanding gesture. Another example of this inventiveness is the “Election Day” section, which juxtaposes on each page the threads of eleven voices,

of an emergency radio bulletin

police CB exchanges

cell phone conversations

and so forth, all of which give a visceral

shock of developing disaster as the gruesome symptoms of the virus run out of control. Here, and elsewhere in the novel, did the idea for

the typographical format come first, or did the material help shape the format?

The individual stories grew in different ways, but in “Election Day” the form came first. I was intrigued by the idea that, at any moment, we are

completely saturated by a babble of language we cannot hear, irradiated by

cell phone calls,

radio waves,

television shows,

songs,

and police, emergency, and military broadcasts.

If we could hear all these voices passing through our heads, we would experience an overwhelming cross-section of our moment in time—public, private, and secret. “Election Day” began as a musical score for radios during a moment of panic. Some of the dialog was invented to tie the webwork together, while other voices were taken from authentic live or transcribed broadcasts. It used to be possible (if illegal) to listen in on other people’s cellphone calls with the right scanner. I also had access to some scanners during a tornado and power outage, and transcribed all the voices responding to the emergency.

I also love the terrifying two-page spread of “Wildfire Vectors”: superimposed over the hazy Mercator map outlines of the world are fifteen swift moments of an as yet unknowing contagion spreading. Over Mexico hovers the tiny paragraph “The actor shares a needle in the back room of a Mexico City canteen, just this once.” Over Brazil hovers “The poet in the São Paolo literary festival licks a joint, passes it to his friends,” over Turkey there’s “The dishwasher in an Istanbul café eats an almost-untouched tea cake,” and then there’s my favorite, “The president of Australia addresses the Parliament.” I’m imagining that when you were writing the book, you came up with far more than the fifteen examples that made the final cut.

To paraphrase your friend Gonçalo M. Tavares, writing is subtraction. Because of the time it took to find a proper publisher, I was granted many opportunities to hone the text.

Ah yes, wandering in the literary wilderness can also be good exercise! So, what was the circuitous route from manuscript to published book?

I finished the first draft of the manuscript in 2005, then began a long tournament of manuscript tennis with every publisher and agent I knew of who seemed sympathetic to this sort of work. I continued to revise for five more years. Beyond the normal pain of rejection, I began to experience biting frustration at version control. From the beginning I had designed Keyhole Factory as a 6 x 9-inch book, but protocol dictated submitting the manuscript double-spaced on letter-sized paper. In my failed effort to second-guess what editors were looking for, maintaining two different versions of the text—the book I wanted and the manuscript I thought somebody else might want—was laborious, and led to mistakes and lost revisions. So I decided to do what was once considered literary suicide: I published my book in a small run on my own label, Spineless Books. You might call this “vanity publishing,” but to me it was “humility publishing.”

I went all out: a handsome hardback with enclosed fold-out map and CD-ROM. I sent this book to a few more agents; I had nothing to lose, and Keyhole Factory presented itself better as an imposing black hardback than as a sheaf of twelve-point Times New Roman.

(Interested writers should note that it’s not clear whether my small press edition helped or hurt the book’s appeal in the eyes of publishers. Apparently, even a well-received tiny run by an insubstantial press can taint a book’s perceived marketability for a house who wants to debut the book—that is why Soft Skull did only paperback.)

There then followed more rejections, mysterious disappearances into slush piles, but also a smattering of applause from a few unexpected readers who liked it, two good reviews, and a cool award.

I never found an agent, but an agent accidentally found me, and interested the notorious independent Soft Skull, a press who has something most larger houses don’t: character.

That’s an inspiring story, how a DIY publishing effort eventually brings you to a sympathetic press. Yet it’s a long haul, too, since you completed an initial version in 2005. Since then, literary novels offering a new apocalyptic end to the world have become a mini-industry in recent publishing. Your novel, however, seems to me to differ significantly from these books, which emphasize exterior disasters (zombies!) that bestow collapse. Keyhole Factory does indeed feature a devastating virus invented in a bio lab that swiftly skims most of the human foam off the surface of the world, but the true virus is the human mind itself, or at least that part infected with what the novel calls “bad ideas.”

Yes, the course of these twelve years has seen a proliferation of post-apocalyptic films, books, TV shows, and even (weirdly) nonfiction documentaries about the end of civilization (National Geographic’s “Aftermath: Population Zero” and The History Channel’s “Life After People”). I don’t know whether Keyhole Factory’s publication is a result of this peculiar groundswell of interest in the end of the world, or a coincidence. I will say emphatically, however, that my novel is not a zombie story. Zombies are not real. You have picked up on what Keyhole really is: a book in which the virus is literal but also a metaphor for the bad ideas of unchecked capitalistic greed and its attendant environmental destruction, notably the proliferation of increasingly expensive, unthinkable, and sickening weapons of mass destruction.

And on a more individual level, it’s how the bad idea of violence and retribution can infect a victim, leading to the spread of more violence and retribution.

The only way to stop a virus, as an international team managed to do with smallpox in 1979, is to deny it any hosts to feed on, to contain it, to starve it out of existence. In the case of bad ideas, the novel raises the question whether eliminating the host—the human mind—will kill them off, or whether ideas can exist without any mind to think them.

Hmm, perhaps our only chance, as a species, is if we can learn how to inoculate ourselves from ourselves. For instance, your novel of the apocalypse was published this fall the same month that your first child, a daughter, was born. So our good ideas, like commitment and hope, might help us prevail?

There are signs the world is getting better. Ideas, good and bad, proliferate faster now. Perhaps there is a survival of the fittest that favors reason and compassion. To me, my new child is proof that people are born without malice. I’d like the good idea that goes viral to be a pandemic vision of a collective well-being.

LINKS AND RESOURCES:

- Here is the Keyhole Factory site, with links to scholarship and online ordering.

- Check out a Web-Work Map of Keyhole Factory, using the techniques of Harry Stephen Keeler.

- Read “On Harry Stephen Keeler,” an essay by William Gillespie for Ninth Letter cited in this interview.

- You can also read “Keep the Change,” an excerpt from Keyhole Factory published on Numéro Cinq.

- Take a look at Morpheus: Bibionaut, a twenty-minute interactive movie, an electronic translation of one of the stories in Keyhole Factory (requires the Flash plug-in).

- What William Gillespie Knows: an interview with John Warner at Inside Higher Ed.

- Finally, check out an excellent review of Keyhole Factory at The American Reader.