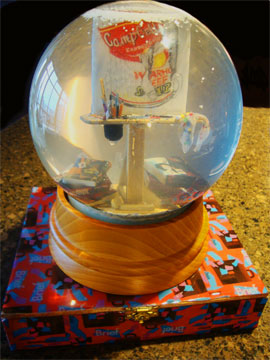

Alexandra Chasin’s second book, the novel Brief (Jaded Ibis Press), resists attempts to write about it not just by virtue of its content or physical layout, but by virtue of having been published in three forms, the most extravagant of which is an $8500 fine art limited edition of the book that consists of a snow globe containing a fake Warhol with a tiny print copy of the book buried in the wooden base. There’s also an iPad app version that’s gotten some deserved buzz. The print version is a black and white paperback as filled with images as it is with text. This review limits itself to the paperback, which, yes, is limiting.

Alexandra Chasin’s second book, the novel Brief (Jaded Ibis Press), resists attempts to write about it not just by virtue of its content or physical layout, but by virtue of having been published in three forms, the most extravagant of which is an $8500 fine art limited edition of the book that consists of a snow globe containing a fake Warhol with a tiny print copy of the book buried in the wooden base. There’s also an iPad app version that’s gotten some deserved buzz. The print version is a black and white paperback as filled with images as it is with text. This review limits itself to the paperback, which, yes, is limiting.

Taking the form of the oral legal brief of an unnamed and ungendered “J. Wanton,” a “vandella,” petitioning an also unnamed judge for clemency in an elided case of art vandalism, the book literally beseeches its presumptive audience to resist a verdict. And by making a historical argument for the inevitability of the vandal’s act, an argument that documents both the long history of art vandalism and the cultural evolution of the nation (and world) from the petitioner’s moment of conception in 1960 to the moment of petition – a fascinating account, by the way – the book literally writes over a contextual swath so broad as to consist of a kind of vandalism of its readership’s collective cultural imagination.

Brief is not without its own, explicit imaginings of what such a broad defacing might look like. Much of the book consists of Chasin’s narrator’s presentation of evidence, evidence he sums as “The ticky-tacky stuff you’re soaking in, call it ideology, call it hegemony, call it Situation Normal All Fucked Upside same rightside up as down.” As the argument transitions from evidence to the claims predicated upon it, the narrator declares in a long rambling sentence:

It’s Cortes whose ship I passed like a ship in the night of the centuries later still his pathways etched in the very wavy water and in the junkyard satellites we use to call the sky when we think about the way we remember him Navy SEALing wax avant la lettre, and see now the way we iterate his non-dit name right here in court his name emblazoned on the cortex of the veal farm, the chain-linked stories of the Mexican border, the mall, the overly Euclidean grid of the cities where graffiti smushiti scratchiti and the vox penitmento you think inside the box of I scream you scream we all scream in the subways and on the billboards reliving the very cemented edifices of sentimentation built on the bloody sand of it we had come in peace don’t you think things would have gone a lot differently.

The narrator’s claim: that his act belongs to a dialectic historical process and that, therefore, the protagonist is neither insane nor culpable nor even, now that he’s stepped out of the stream of time, capable of a repeat offense. The book continually alludes to this process’s Hegelian nature, arranging its evidence as an external but compelling history, referencing Leninist-Marxist-Feminist cells and almost pathologically pairing antitheses, such as the one above: the book’s broad cultural defacement and Cortes’ violent, imperial remaking of physical, geographical history.

This claim of Hegelian dialectical inevitability – a claim that Hegel’s account of history as a dialectic process in which antitheses collide and form syntheses that march towards a progress and goal that the antitheses cannot independently see, and which accounts for the narrator’s act of vandalism – leads towards two readings of the book. In the first, the book seems to argue that all art rewrites the cultural imagination, all art changes the viewer’s perception and experience of the art that precedes it, and, thus, performs the kind of dialectic action by which Chasin’s protagonist claims to have been swept up. In this reading, art is a part of history aimed at a telos, or a specific endpoint, and art vandalism is simply another way of showing what art is, and of being art.

The absurdity of the brief’s argument – culture made me do it, your honor – is one that’s long been polarizing and problematic in our national discourse about criminal behavior in other spheres. Chasin’s narrator references the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham. He points out that in that case insanity was a successful plea for one defendant whereas the cultural and historical forces of 1963 race relations were not. The argument for cultural forces beyond the actor’s control is one that, much like an insanity plea, exculpates by denying the possibility of the actor’s agency. In the Massachusetts Review [Spring 2012 issue, Vol 53 Issue 1], I’ve argued that this denial of agency is the central tenet of continental postmodern art. That art claims that because it cannot control the unique subjectivity of its viewers, it cannot be held responsible for any interpretation of it, and therefore need not bother to attempt to represent anything. I think this book agrees with my claim and participates in that discourse. Chasin’s narrator offers his claim of dialectic compulsion in opposition to a psychiatric diagnosis that the petitioner wishes the judge to dismiss, expecting that “It might be the first time in history an artist is proved to be sane.”

This then is the binary: either the artist (as vandal) has no agency or the artist is mad. Neither position is satisfying, legally speaking; as novelistic content, both are fabulously entertaining.

I think, though, that Chasin’s book not only understands that its binary is unsatisfying, but wants to vandalize itself, to vandalize its argument, its neat dialectical history, its Enlightenment understanding of art and progress and social consciousness, and most of all its red herring antithetical relationship between inevitable progress and madness. I think Chasin, like her narrator, “wanted to bring the art absolutely up to date, to retrieve it from art history and give it life.” I think it argues that the Vandals sacked Rome because they could, not because they were participating in some great historical inevitability that would eventually allow for television and nuclear weapons and Andy Warhol and Dadaism. And if art has agency to destroy itself because it wants to, then it also has the agency to make itself as it wishes, to be unpredictable, to create newness, to seize power, and to rebel against its critics’ definitions. In short, art with agency beyond the critic’s account is alive.

And that rebellion against critics’ definitions is not without its stakes. Categorizing art makes it safe. Categories tell us what to think and how. We’re comfortable with the fragmented woman in a painting when we understand Cubism. We know that it’s bad to vandalize works we’re told are masterpieces. Chasin’s book unwrites definitions, and that’s its real power. So don’t allow me to define it for you; better that you pick up your own copy and read for yourself its 178-page mesmerizing brief without the safety of knowing what you should think about it.

Further Links and Resources:

- For more on Alexandra Chasin and her work, please visit her author page on Jaded Ibis Press. There you can also take advantage of the opportunity to special order the Fine Art Limited Edition of Brief (pictured at right). Yours for only $8,500.

- Check out Elatia Harris’s interview with Chasin on 3 Quarks Daily.

- And here are Five Questions for Alexandra Chasin on Experimental Literature posed by Christopher Higgs for HTMLGIANT.