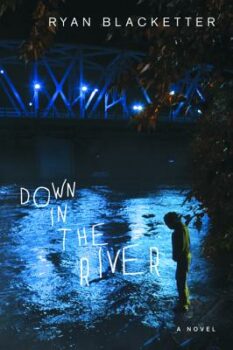

It’s a shame people don’t trade gifts for Halloween. If they did, Ryan Blacketter’s debut novel, Down in the River, released Jan. 6 by the independent press Slant, would be a perfect pumpkin-stuffer.

It’s one of those rare novels in which everything is working, all at once and in harmony—the characters are interesting, authentic, and sympathetic; the plot absorbing and relentless; the descriptions sharp; the dialogue layered; the prose tight and muscular. For fans of Edgar Allan Poe’s macabre tales, or Cormac McCarthy’s stark landscapes and unholy pilgrimages, or Flannery O’Connor’s grotesque, violent, bullheaded characters, Down in the River will certainly satisfy. It’s also the sort of book that will appeal to readers who appreciate the empathy Andre Dubus extends to even his most criminal subjects. In fact, Down in the River combines the most distinctive elements of each of these luminary authors:

Poe

The novel’s central action is as ghastly and morbid as anything Poe thought up, maybe more so because of its hyperrealism—stealing a corpse from its grave.

The story focuses on Lyle Rettew, a teen from the mountains of Idaho whose family has recently migrated to Eugene, Oregon, after the suicide of Lyle’s troubled twin sister, Lila. Lyle is haunted by her memory, especially because his older brother, the family patriarch, disposed of her remains secretly and has prohibited the family from speaking about her or looking at her photos.

In Eugene, Lyle falls in with a boy named Martin, an outcast and painter whose rival has stolen his girlfriend and social club. This rival also has a dead sister, and when Martin suggests that they “rescue” her remains from a mausoleum, Lyle takes action, driven by a longing for his own sister’s peace and an increasing mania, from his refusal to continue taking his lithium.

The result, rendered in full sensory detail, is every bit as gripping and disturbing as Poe’s famous horrors. Blacketter sends Lyle and Martin to a hilltop cemetery at night during a hailstorm, and then inside the damp mausoleum where the coffin rests, lit by the boys’ tipping flashlight and a flickering vigil candle. Blacketter lets Lyle pry open the coffin’s lid, scrutinize its contents, and, with reverence and kind words, remove them:

When he walked out to the cold wind and the wrestling shadows, Martin waited outside the gate smoking.

“She’s so light,” Lyle said. “She doesn’t weigh a thing.”

“Motherfucker.” His friend skipped off a ways. He dropped the flashlight and ran, ice bits falling in its beam.

McCarthy

The girl’s body spends most of the rest of the novel in Lyle’s backpack while he travels through countryside and cityscape, mostly at night. Blacketter takes us into orchards and glades and forests and playgrounds, into dirty parking lots and churches and hospitals and prisons, through rain, hail, snow, blinding sunshine, fog, and wind. He is constantly embedding the novel’s action in lucid descriptions of the shifting weather and landscape, so that Eugene becomes a place as vivid and significant as McCarthy’s Texas hardpan in No Country for Old Men and his post-apocalyptic wasteland in The Road, among others.

Further, Lyle’s travels become a journey-story. He is quickly abandoned by Martin, who prefers philosophy over action, and so he sets out on his own both to deliver the girl to some more honorable fate and to flee the consequences of his crime. This is an odyssey, like the odysseys in McCarthy’s novels, at once sacred and blasphemous. In No Country for Old Men, McCarthy has his traveling hit-man flip a coin for people’s lives while the sheriff who chases him pontificates about a society that needs people to care about each other. In The Road, a father ushers his son through a lawless wilderness that includes cannibals, stumbling upon the means of their survival, always willing to sacrifice his own needs to fill his son’s.

Like the sheriff and father, Lyle has honorable intentions. Churchgoers had long called Lila “a whore, a witch, and a vandal,” and the church has banished Lyle’s family for the moral stain of her suicide. He suspects his sanctimonious brother of throwing her ashes out the window of his truck. And prior to his departure Martin has convinced Lyle that this other dead girl suffered similar disrespect, explaining that mausoleum burial goes against the Judaism of her now-converted family:

You’re supposed to take care of people when they die, to take care of your family. It’s important. The ceremony, the burial—it all has to be just right. You don’t just slop them someplace. It ruins their memory, it disrespects their life.

Lyle wants to offer this corpse the veneration of which his own sister has been deprived. He has been convinced that his crime is “about real morals, not about following rules,” as Martin puts it. Like the humanistic characters in McCarthy’s novels, he is driven by duty and compassion.

Carrying the girl in a backpack, however, is an obvious desecration, especially when he invariably becomes disgusted by and indifferent to the remains. He ends up tossing his backpack all kinds of inappropriate places: into an orchard, onto a café roof, behind the folded sweaters in his new girlfriend’s closet. This calls to mind McCarthy’s amoral hit-man and cannibals, not to mention the judge in Blood Meridian. Lyle is also, like them, half crazy. He suffers from bipolar disorder, which was the reason for his lithium prescription, leaving him with a crowded mind and manic wildness after he ceases taking the drug.

It suggests to Lyle a world that might be empty of any power greater than that created by humankind, one driven by little more than accident and chance:

A half block up the road, flashing gates lowered at the tracks. Red lights slanted across the snow. After the horn bawled, the freight train flew into view, wheels shrieking like insane birds. The ground shook, and the shrieks went on. [Lyle] held his palms against his ears, wincing, until the train hurtled away down the track.

“Did you see a conductor on that train?” he said.

“Why do you sound so worried?”

“These trains are running by themselves. What’s going on?”

These unguided trains continue to intrude on the action, and their emptiness continues to trouble and confuse Lyle through the novel’s final sentence.

O’Connor

In this way, Blacketter’s novel deals with the same preoccupation that obsessed O’Connor—the conflict between signs of the world’s emptiness and its beacons of religion. Like Lyle, who runs from a home drenched in religion, steals a small bag of meth, and bloodies his pious brother’s mouth with a rock, O’Connor’s characters are always trying to deny their religious impulses by seeking out emptiness or depravity. Martin seems to justify this behavior when he gives Lyle a little sermon about a world that deserves rebellion, one that could have come directly from O’Connor:

Have you ever noticed that when you drop something on accident it shatters, but if you drop something on purpose it doesn’t even crack? It’s what I call The Great Fuck You. The world knows who you are and it goes against you.

Like O’Connor’s characters, Lyle is fleeing from a religious presence he can’t quite seem to escape. He says, “I’m sick of Jesus,” but he’s enjoying the warmth and shelter of a church when he says it, and the careful phrasing of the line indicates not only a rejection of religion but also a confirmation of its persistence in him. It’s easy to imagine similar dismissals coming from the intellectuals in O’Connor’s “Good Country People” and “Everything That Rises Must Converge.” And like O’Connor, Blacketter makes this conflict grotesque, not only with small absurdities but also by letting Lyle’s mental illness skew his perceptions:

Blocks ahead, on high, the cross on Skinner Butte leaked bits of sickly light. The faces of church people smiled up at him from the wet sidewalk. They gazed sympathetically from the branches of trees and harassed him with whispered prayers from passing windows. He saw his brother smiling, Bible in hand.

He also sees a spotlight moving on the clouds, “as if the light operator were stirring up the heavens,” metaphorical imagery that calls to mind the turnip-shaped cloud that chases Shiftlet at the end of “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” or the sky empty of both sun and clouds while the grandmother begs the Misfit for her life in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.”

And like these characters, Lyle’s increasing distress drives him toward the greater mysteries buried beneath the superstructure of religion. Late in the novel, Lyle returns to the church where he claimed to be sick of Jesus. He accosts a priest in a motorized wheelchair, trying to save himself with the same empty begging as the grandmother in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”: “I want to be a Catholic,” he blurts, and later, “I’ll say a thousand Hail Marys.” The priest questions his sincerity, and this leads to a real change later. Near the end, when Lyle has lost almost everything, he tells his brother, the antagonist:

“I’m different now. Something happened in me. I don’t know what it is. But something did. I won’t take any more speed. I’m done throwing rocks. I don’t blame anybody. Not you or anybody else. I want to care about people.”

Is there any greater innocence and grace than this? He recognizes his own flaws and limitations while turning his heart toward others. It’s the same kind of gesture O’Connor always provokes from her characters, as when the grandmother touches the Misfit and calls him her child.

Dubus

But what makes Lyle so deeply sympathetic, ultimately, is that he has shown that he does care about people. And what makes this novel so warm and heartbreaking despite its gruesome material is that all the characters are driven by their love and concern for each other, even as they commit their atrocities.

Dubus is often recognized as one of America’s most compassionate authors, but his characters are at times as dark and unscrupulous as Blacketter’s. In “Killings,” for example, a father premeditates and then carries out a cold-blooded murder, executing the man who killed his adult son. The story, however, is devoted to humanizing both murderers, demonstrating their love and grief and sensitivity to the pain of others. The premise from which Dubus writes is nicely summarized in this story, when one character says, “Ever notice even the worst bastard always has friends?” Dubus never makes a villain of any of the easy targets in his stories, and that’s what makes him such a compassionate writer.

Dubus is often recognized as one of America’s most compassionate authors, but his characters are at times as dark and unscrupulous as Blacketter’s. In “Killings,” for example, a father premeditates and then carries out a cold-blooded murder, executing the man who killed his adult son. The story, however, is devoted to humanizing both murderers, demonstrating their love and grief and sensitivity to the pain of others. The premise from which Dubus writes is nicely summarized in this story, when one character says, “Ever notice even the worst bastard always has friends?” Dubus never makes a villain of any of the easy targets in his stories, and that’s what makes him such a compassionate writer.

Blacketter does the same. Lyle is clearly disturbed, but Blacketter never lets him become a caricature, never lets his mental illness cloud his personality or override his humanity. Like Dubus’s characters, even his most terrible deeds are driven by noble impulses and understandable grief. In the mausoleum, for example, Blacketter shows the love and respect behind Lyle’s robbery when he tells Martin, “Hey, don’t shine [the flashlight] in her eyes,” and, “Let’s not curse in here, okay?” He attacks two teens on a bridge, threatening to kill them, but only because they won’t leave in peace the goose that is dying there. “You’re like some kind of protector,” says Rosa, his new girlfriend.

Similarly, while Lyle’s brother Craig is an antagonist, he’s never a villain. His ideas about good and evil are simplistic, but he’s driven by grief and by a legitimate concern for his troubled family, whom he is supporting financially and trying his best to hold together. He has outlawed references to Lila to soothe their despondent mother, and he chases Lyle because Lyle is clearly out of control. So was Lila before her death, her last years blighted by meth abuse. Her recklessness and ultimate suicide seem to justify Craig’s good intentions, even as Craig’s methods for carrying out those intentions justify Lyle’s anger:

“Don’t make me out to be some kind of—I had to do something. She was insane, buddy, and, I believe, demon possessed. I only tied her twice. You think I liked it?”

There is also Rosa, who ends up becoming Lyle’s accomplice. She accepts the burden of this affiliation because she so badly wants to help him, and Lyle cares for her so deeply that he ends up putting her well-being above his own. She is also from a troubled home, and, like Lyle, torn between repugnance and concern for her family. Blacketter lets us sympathize with both characters’ desire to escape by showing the strife they face at home, but he also humanizes them with their concern and regret about leaving, as when Rosa initiates this exchange:

“I have to go. It’s been two days. My dad’s been worrying about me this whole time.”

“What did I do to my brother?”

“I have to see if my dad’s okay. I’m cold, and my feet are wet. I’ll talk to you tomorrow.”

She ends up taking Lyle and his gruesome backpack with her, another awful decision, but one motivated, yet again, by basic kindness.

This is what the novel really aims to explore: the complications that arise from these trials and loyalties and failures. Readers, critics, and publicists often focus too heavily on what a story is about rather than where it goes, what the subject matter is rather than what the author does with it, where the story begins rather than where it carries us. The best stories channel all the variety of their subject matter to the same place. They use it to worm into those mysterious depths that underlie human experience, those facets of existence we can each recognize despite the different lives we lead—connection, compassion, loyalty, betrayal, loss, failure. Those are the depths that Down in the River taps, and what will make it an enjoyable and meaningful read for anyone whose heart is still beating, whether or not they are naturally drawn to the dark.