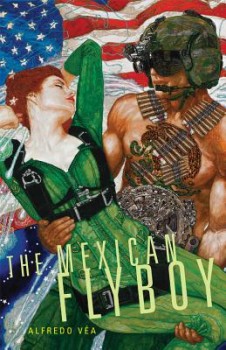

A professor-poet with a traumatized past straps on a time machine and whisks away victims of injustice from horrendous death. Alfredo Veá’s new novel, The Mexican Flyboy (University of Oklahoma Press), described in this way, sounds suspiciously like a Marvel comic. The professor-flyboy himself, Simon Vegas, certainly has cultural cousins in Superman and other airborne superheroes. A reader might, then, expect a narrative structured around the traditional hero’s quest, in which someone—usually young—is singled out for a particular and dangerous goal. This young hero must surmount significant obstacles, which not only drives the action forward but also creates the opportunity for both outward and inward voyages for the protagonist. Yet while The Mexican Flyboy seems to initially adopt such a structure, it quickly asserts itself as a historically rich, deeply literary, and passionate work intent on a different mission. The narrative pursues its own idiosyncratic line of inquiry, and this departure turns out to be also part of its point.

The main character, Simon Vegas, first appears—somewhat mysteriously—as a lost, traumatized, highly sensitive Irish-Mexican six-year old, asking for work in a vineyard in California. Very much the archetypical, orphaned hero, his call to action comes when a woman falls from the sky without opening her parachute. The desire to catch her in his arms, to soften her blow and save her from death, galvanizes the boy and becomes his life’s goal.

If this novel were to follow the prototypical quest structure, various complications would subsequently arise—and often of increasing challenge—allowing the hero to come of age as the narrative progresses toward its end goal. Veá, however, handles this differently, subverting the reader’s expectations by moving forward in time, offering us a portrait of Simon happily married and awaiting the birth of his daughter, while putting the final touches on his time machine, a customized Antikythera. The fictional use of this actual calculator (dating from the second century B.C.), signals both the author’s depth of knowledge and his ease at turning history into fiction, part of the book’s charm, and we are soon treated to a highly-imagined swooping rescue of Ethel Rosenberg, just minutes before her death in the electric chair. The scene manages to embrace horror, historical accuracy, and the comic, with Mrs. Rosenberg giving Simon—who is disguised as Bette Davis—her tips for cooking brisket in addition to a poignant denial of her guilt. Her alternate fate, and the fate of all rescued by Simon and his ancient device, will be a Floridian beach paradise, where, with historical creativity, they are assigned housing and then allotted flip flops, poolside drinks, and Hawaiian shirts, sewn by none other than the young women who perished in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

Having the hero perform his first rescue a mere two chapters into the story continues to reinforce the ways in which Veá seems interested in working against the traditional quest narrative. Rather than follow the form’s established tropes and patterns, Veá choses to give us a fuller picture of Simon’s past, as well as a portrait of his current domestic happiness as he and his wife expect their first child, his involvement with prisoners in the penitentiary where he teaches poetry, and a scene in which he goes off on a wild riff on radio—a clue to his passions. From there, we return to Simon’s own birth, glimpse Amadou Diallo in custody, and are privy to a long and highly detailed conversation about lethal injection and its recent failures. So instead of character development, we have backstory. Instead of obstacles, we have polemic. Clearly, The Mexican Flyboy, while bearing superficial resemblance to tale of heroic rescue, is driven by some inner logic of its own.

Having the hero perform his first rescue a mere two chapters into the story continues to reinforce the ways in which Veá seems interested in working against the traditional quest narrative. Rather than follow the form’s established tropes and patterns, Veá choses to give us a fuller picture of Simon’s past, as well as a portrait of his current domestic happiness as he and his wife expect their first child, his involvement with prisoners in the penitentiary where he teaches poetry, and a scene in which he goes off on a wild riff on radio—a clue to his passions. From there, we return to Simon’s own birth, glimpse Amadou Diallo in custody, and are privy to a long and highly detailed conversation about lethal injection and its recent failures. So instead of character development, we have backstory. Instead of obstacles, we have polemic. Clearly, The Mexican Flyboy, while bearing superficial resemblance to tale of heroic rescue, is driven by some inner logic of its own.

This becomes even clearer near the novel’s end. On a long drive together, Simon shares with his friend Zeke his motivations. When Zeke challenges Simon directly about his last-minute rescue missions, asking, “Who on earth does this help?” Simon answers, “Every person I lift makes me feel a little more weightless.” Clearly he feels heavy with the world’s injustices. Each rescue is a small unburdening.

Part of the burden, as he goes on to explain to his friend, is the fear of his own culpability. He describes to Zeke how, when he enters the scene of battle or public execution, he scans the watching crowd:

“…I winnow through the audience. Going carefully from face to face…. I am terrified by the possibility, no, the probability, that I will see my face there among them, […] my spirit changing color to match my bishop’s robes, my colonel’s tunic, my sagging pants, or my shiny badge.”

He refers to an incident in Viet Nam, in which he shot a young child; it has haunted him throughout his life. Recounting the incident to Zeke, he says, “My brown Mexican face turned olive-drab. I had become a slave.”

Veá takes the word “slave” seriously. Simon’s quest does not so much drive the narrative as form its central metaphor for the real propeller: a hortatory call to freedom. Positions are not equivocal, either, and we hear the author’s voice speaking clearly through Simon as he continues to explain to Zeke:

“Maybe if I can hear and see and learn about every cruelty of the past, then maybe….maybe I can be ready to hear cruelty and see cruelty in the here and now. We are all so blind in the present. […] Maybe I can see the very moment when I am relinquishing my own will—handing it over, lock, stock, and barrel, to my time, my place; to a mob, to a culture, to a queue, to a fashion—to an order being shouted over a walkie-talkie. Only when I know when I’m not free can I set myself free. If I am everybody…then I am nobody.”

In an attempt to categorize the structural framework of this novel, then, Simon Vegas’ rescues might be viewed as a kind of serialization—the on-going account of a lone man’s struggle to relieve wrongful suffering. So in contrast to a traditional story that ends when its quest has been completed, the reader is instead forced to reckon with the fact that there can be no tidy conclusions when there is continued unfairness and inequality in the world. Underpinning this position is a court-room argument against not only capital punishment but all forms of injustice that condemn people to terrible deaths because of racial hatred, or the numbed absurdities of war, or ethnically-motivated suspicions, or fear of the unconventional. Yet what might be lost in forward momentum by adopting this approach is more than made up for by the elaborate back stories that enrich our understanding of what is, in fact, a noble character wracked by sorrow over the state of the world. And the reader will find that what stokes the novel—and where the narrative draws its power–is its rhetorical fire.

Most salient, however, is the way in which Veá inhabits his characters to evince what is clearly a deeply felt responsibility toward the victims of wrongful death. Just as he wants us to look closely at people condemned by the legal system or tribunals, he notices the details that others might overlook. The rubber wheels on a cart in prison, for instance, are observed with the beautifully sympathetic description of being “long-suffering.” He turns a sympathetic eye, similarly, to the most minor of characters. Flo-Masta, a prisoner in the penitentiary who has turned floor-cleaning into a science, is “an old elephant trapped forever in a cage at the zoo, his mop swayed like a trunk from side to side…” And if this were not painfully evocative enough, Veá continues:

Now he [Flo-Masta] was moving down the middle of the corridor, inscribing one sign for infinity upon the next and the next, a thousand reclining figure eights lying one upon the other like geological strata laid down only to be buffed away.

In this one poignant sentence, the author calmly evokes despair: the eternity of the prisoners’ sentences, the infinite number of the incarcerated, and the invisibility of their lives. The prisoners’ fate is made almost unbearable by the masterfully light-weight phrase “buffed away.”

The Mexican Flyboy is a work of enormous ambition, marching to its own passionate drummer. It transcends ethnic labels. It is an idiosyncratic, encyclopedic, verbose, sensitive, flawed but big-hearted cry for us to pay attention to each other, to be generous, to read widely, to study and remember the past, and, most especially, to resist any doctrine that causes harm. Unsparing yet deeply generous, Alfredo Veá manages to embrace the horrific and urge us to image ourselves in a better way. It is hard not to feel transported—both off the page and, if briefly, to Boca Raton—by the novel’s charm and sense of mission.