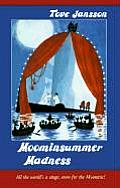

Moominsummer Madness begins, as perhaps all good children’s books should, with a map of the area of the story, showing the places where significant events happened. It is hand-drawn and gracefully lettered. Like the maps drawn by Ursula LeGuin, Arthur Ransome, and J.R.R. Tolkien, it provides both anticipation and reassurance: we are entering a new and unfamiliar terrain, exciting things will happen here. The book is filled with pen-and-ink sketches of its characters, and the pictures of the inhabitants mean that Jansson doesn’t have to spend as much time describing them, and can focus instead on the plot. Events move along at a clip, beginning with a flood, and moving through the rescue of orphans and destruction of property, the staging of a play, a mystery in a haunted theater, and many other small troubles, all in 150 or so pages of large print.

Moominsummer Madness begins, as perhaps all good children’s books should, with a map of the area of the story, showing the places where significant events happened. It is hand-drawn and gracefully lettered. Like the maps drawn by Ursula LeGuin, Arthur Ransome, and J.R.R. Tolkien, it provides both anticipation and reassurance: we are entering a new and unfamiliar terrain, exciting things will happen here. The book is filled with pen-and-ink sketches of its characters, and the pictures of the inhabitants mean that Jansson doesn’t have to spend as much time describing them, and can focus instead on the plot. Events move along at a clip, beginning with a flood, and moving through the rescue of orphans and destruction of property, the staging of a play, a mystery in a haunted theater, and many other small troubles, all in 150 or so pages of large print.

Tove Jansson’s Moomin world, created in the 1940s, is still quite popular in Japan (there is a Moomin theme park there, and another in Jansson’s native Finland), but few of my American contemporaries seem to have read these books as children. This may be because they are very strange.

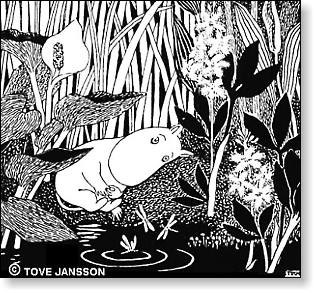

The Moomins are a family of small hippopotamus-like creatures. They are thoughtful and inquisitive, and their personalities are only half decided by their names. Creatures is really the only word to describe the other beings that populate the landscape. Some include Whomper and Misabel, more or less human-looking, but with snuffly animal-like noses and hair; there is the Fillyjonk, a mousy female who is excessively and nervously concerned with cleanliness; there is the bossy Hemulen, who looks a bit like the Moomins but who contains none of their creativity or calm; there is Snufkin, a shy, self-possessed, wandering musician. And finally, there is Little My, small enough to curl up in Moominmamma’s knitting basket, and prone to throwing fits and biting people’s ankles when she is annoyed.

If this sounds a little overwhelming, it can be—I remember trying to keep everyone straight as a six or seven year old first reading Moominsummer, and getting distracted by the sounds of the names, which in retrospect are onomatopoeic. But Jansson refuses to explain or introduce each character—the newer edition I purchased lately does include a sort of glossary in the back, but I don’t remember any such thing in my childhood copy. Jansson would never condescend to her readers by assuming something needed to be explained, yet there is plenty of irony and sly wit here that adults will enjoy. She never winks at adults at children’s expense, however. The troubles at stake here matter, as does the joy.

The adult characters in the story often behave with the irrationality and the curiousness of children, and their world is just as attractive to me now as it was then in its mixture of routine and adventure. Moomins need to eat and sleep, and they like to be warm and cozy, but they don’t worry too much about going to bed on time, or ownership. When their house is flooded, they cut a hole in the ceiling and dive down for cups and plates:

“I’m not washing any dishes today,” Moominmamma said hilariously. “Who knows, perhaps I’ll never wash dishes any more. But please, can’t we try to save the drawing room suite before it spoils?”

The Moomins may be relaxed, but they are also resourceful and humorous, often both at once in a way that will make you wish you could deal with life with such aplomb. When the storm that will flood the valley arrives, Moominpappa asks, “Did anybody take the hammock in?” No one had remembered the hammock. “Good,” said Moominpappa. “It was a horrid color.”

There are more than a half-dozen books in the Moomin universe, and they each take their beginnings from the seasons and events in the natural world. Jansson grew up spending part of each year on an island off the coast of Finland, the daughter of a sculptor and an illustrator. She subsequently lived there with her partner, the artist Tuulikka Pietelä. Moominsummer Madness captures the laziness of sunny summer days and the mystery of summer nights. After Shakespeare, there is a play, with a lion in it. And there are some of the same confusions and tangles of A Midsummer Night’s Dream as characters misunderstand each other, or willfully persist in wanting things that they can’t have.

The other books in the series likewise explore how nature affects our doings and our moods: in Moominland Midwinter the family munches pine needles to keep their bellies full while they hibernate, and we follow the strange little creatures who come out in the snow. A comet and an ocean voyage begin two other books, and always Jansson makes us aware of the trees, the rain, the moon that (in English at least) seems to give her dreamy title family their name.

The other books in the series likewise explore how nature affects our doings and our moods: in Moominland Midwinter the family munches pine needles to keep their bellies full while they hibernate, and we follow the strange little creatures who come out in the snow. A comet and an ocean voyage begin two other books, and always Jansson makes us aware of the trees, the rain, the moon that (in English at least) seems to give her dreamy title family their name.

Most children’s books manage to impart some kind of message; the measure of any book is how well it manages to make you forget that there is any message in it. In Jansson’s world the message is always subordinate to the sheer energy of the plot, but certain ideas gradually become clear: that some people are lonely, and that if you are kind to them they will be less so; that authority figures are often not to be trusted, but that they are cruel or bossy out of loneliness themselves. Some creatures here take on our own neuroses: they cry that the sky is falling, they are a little mean or scary, they get anxious and worried and lost, but others prove that nothing truly horrible ever comes to pass if you keep calm, although a little civil disobedience isn’t out of place either. The theme of loneliness often returns, usually precipitated by the atmosphere of the natural world. There is plenty of action, but characters also often have to go off and sit by themselves and think, whether to pout or reflect or figure out how they feel.

This is a major reason children (and adults) should read these books today: in a contemporary time where there is always something to do, often a rather shallow electronic distraction, Jansson shows that quietly sitting and thinking by yourself is a valuable activity. She also shows that almost everyone is lonely from time to time, and that while community can be an antidote to loneliness, we can also learn from solitude. Being happy all the time shouldn’t be our goal.

The one character who is never lonely is Little My. Perhaps she’s so ferocious to make up for her size—instead of being sorrowful she gets mad. And when she’s alone she always entertains herself, by cutting up balls of yarn, for example, which is fun in a destructive and pointless kind of way. There is also a minor character who may always be lonely: the Groke. She is drawn as a kind of slow-moving yeti, and she’s always cold. She wants to get warm, so she creeps toward any light, but as soon as she sits down on it to heat herself up, she puts it out. Her frightening, endless search is one aspect of the novels that moves them firmly out of the realm of “cute,” although plenty of the characters, especially the Moomins’ big velvety noses and the pleading eyes of the smaller creatures are exactly that.

The one character who is never lonely is Little My. Perhaps she’s so ferocious to make up for her size—instead of being sorrowful she gets mad. And when she’s alone she always entertains herself, by cutting up balls of yarn, for example, which is fun in a destructive and pointless kind of way. There is also a minor character who may always be lonely: the Groke. She is drawn as a kind of slow-moving yeti, and she’s always cold. She wants to get warm, so she creeps toward any light, but as soon as she sits down on it to heat herself up, she puts it out. Her frightening, endless search is one aspect of the novels that moves them firmly out of the realm of “cute,” although plenty of the characters, especially the Moomins’ big velvety noses and the pleading eyes of the smaller creatures are exactly that.

My two favorite characters, then as now, are Snufkin and Little My (read a conversation between them at the end of this review). Neither of them is exactly cute, and if they are, they’re attractive only in their perversity. Snufkin is the most independent character in the book; he is nonchalant but stubborn—a poet-transient who wanders into and out of Moonminvalley each year. Little My is also stubborn, but she’s loud. She enjoys a little entertaining chaos, but she’s happiest when she’s in charge.

As a child, I found the series fascinating for its balance of family security with freedom from convention and control. I’m apparently still as attracted to a world where I can imagine myself as a dreamy song-writing anarchist who is prone to defiant ankle-biting when she doesn’t get her way.

It was Snufkin himself in his old green hat who now stood on the shore and stared at the workbasket he had caught.

“By my hat, if it isn’t a small Mymble,” he said and took the pipe from his mouth. He then poked at Little My with the crochet hook and said kindly: “Don’t be afraid!”

“I’m not even afraid of ants,” replied Little My and sat up.

They looked at each other.

The last time they had met, Little My had been so small as to be nearly invisible, so it wasn’t very strange that they didn’t recognize each other now.

“Well, well, dear child,” remarked Snufkin and scratched his head.

“Well, yourself, with knobs on,” said Little My.

Snufkin sighed. He was here on important business, and he had really hoped to be alone for a few days more before returning to Moominvalley for the summer. And then some careless Mymble went and put her child to sea in a work-basket. Just for the fun of it.

“Where’s Mother?” he asked.

“Somebody ate her,” replied My untruthfully. “Have you any food?”

Snufkin pointed with his pipe stem. A small kettle of peas was simmering over his camp-fire nearby. Beside it stood another with hot coffee.

“But I suppose milk’s what you drink,” he said.

Little My gave a contemptuous laugh. She did not bat an eyelid as she swallowed two brimming teaspoonsful of coffee and ate no fewer that four peas.

Then Snufkin carefully extinguished his camp-fire with water and remarked: “Well?”

“Now I want to sleep some more,” said Little My. “I always sleep best in pockets.”

“Quite,” said Snufkin and pocketed her. “The main thing in life is to know your own mind.” He tucked the angora wool in around her.

Then Snufkin continued his way across the meadows by the shore.

If you enjoyed the Moomin books, you might also like Jansson’s The Summer Book, a collection of stories based on her childhood, recently reprinted by Sort Of Books. A Winter Book, which contains her other fiction for adults, is also available.