I.

I always knew that my older sister, Caren, was a great character. The first time I tried to write about her was in the fourth grade, when our teacher asked us to tell a story about a family member in our journals. After a couple of false starts, I decided it was too much to try to explain Caren in a couple of paragraphs, so I ended up with a narrative about Scruffy, our family dog.

I wanted to write about her countless times after that—in longer pieces, in shorter prose, in academic terms—but figuring out the best approach was consistently daunting. A nonfiction piece on the effects of traumatic brain injury on families, a tearjerker about how she’d almost died, a short story imagining what this must have been like from my parents’ perspective, or a longer work recounting the struggles she’s faced due to her unique place in the world?

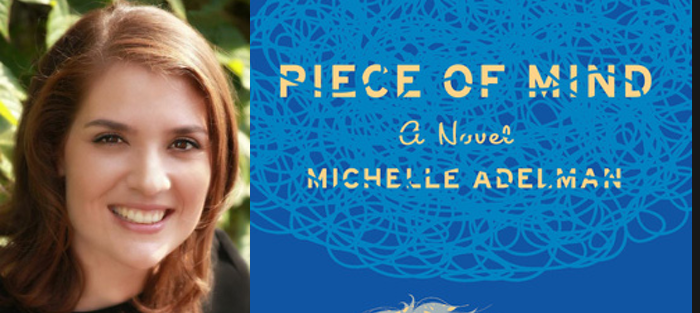

It wasn’t until I began writing a fictional version of Caren that I found I had something to say. Of course Lucy, the protagonist of my novel, Piece of Mind (W.W. Norton & Company), is not my sister, and my sister is not Lucy, but my sister’s character invariably shaped the creation of my protagonist. I was in the final stages of my MFA program when I realized that I knew a character with a potential story that hadn’t yet been written, someone who, like my sister, was funny and oftentimes unfiltered, perceptive in unexpected and surprising moments, and yet challenged in complex ways. She was smart and well read, for example, yet struggled with basic responsibilities, such as cleaning and organizing, tasks related to executive functioning, functions that were damaged when she was hit by a bus at the age of three.

It wasn’t until I began writing a fictional version of Caren that I found I had something to say. Of course Lucy, the protagonist of my novel, Piece of Mind (W.W. Norton & Company), is not my sister, and my sister is not Lucy, but my sister’s character invariably shaped the creation of my protagonist. I was in the final stages of my MFA program when I realized that I knew a character with a potential story that hadn’t yet been written, someone who, like my sister, was funny and oftentimes unfiltered, perceptive in unexpected and surprising moments, and yet challenged in complex ways. She was smart and well read, for example, yet struggled with basic responsibilities, such as cleaning and organizing, tasks related to executive functioning, functions that were damaged when she was hit by a bus at the age of three.

The writing started with snippets of a story, a scene imagining Lucy breaking up with a potential beau. It was meant to be a lighthearted, humorous take on a quirky relationship. But when I received the first feedback from my workshop, I knew instantly it could be more. There was no quiet shrugging or polite nodding in this class; it was a group divided by a clear visceral response: The “I am her, and she is me!” camp battled against the “This character is irritating, and I don’t like her!” faction. Of course my peers’ insights were more nuanced than that, but the fact that they reacted so strongly made me appreciate that there was something in this character that spoke to people on a deeper level. I decided then that I was going to attempt to write a novel.

When I started, I imagined Lucy from the third-person perspective. It seemed to me that this voice would allow for the most freedom to step outside of the protagonist’s world and to inhabit other minds. I knew firsthand the effect a particular disability can have on families, and I wanted the chance to convey the rippling consequences of events from different angles. The notion of writing her first-person was initially unthinkable; I was worried I’d feel trapped by Lucy’s quirky voice and limitations, and I didn’t want the portrayal of how other people saw her to be a reflection solely of her own lens. I wanted the ability to contrast her perceptions with reality, and vice-versa. Perhaps most significantly, first-person seemed like the riskiest choice. Who was I to attempt to burrow inside a brain-injured head?

Yet after writing the first draft of several chapters, I made the move to “I” at the suggestion of some of my earliest readers, who instantly found Lucy’s voice more compelling than that of any of the other characters. She was dominating the pages, so why not let her speak freely and take ownership of the story? The voice was already in my head—her cadences, her speech patterns, her questioning of the world—as I had been writing her in a very close third-person from the start. I had envisioned the book as alternating chapters and voices, and letting go of the other voices meant I had to re-imagine these characters slightly from Lucy’s perspective. But as I wrote, I found it liberating to transfer Lucy’s voice directly to the page, to try to reimagine the landscape I’d known from her unconventional vantage point. Scenes began to pop and come alive when she was narrating, and I realized it was her story.

When the more emotional elements of the plot began to unfold, however, that excitement turned to doubt, and a resistance to write those scenes led to eventual stagnation. I questioned my authority and ability to accurately portray pain and confusion through the lens of an injured brain. I wondered how I could precisely mirror the feeling of being lost in a city with impaired executive functions. I didn’t want to mock the sense of fear and disorder, but I didn’t want to depict it in a sappy or disingenuous way either. I needed to stay true to the energy and humor of the character.

I stalled for long enough to allow life to mirror fiction. Months after my father died suddenly and unexpectedly, just as the character of the father dies in the book, what should have perhaps been an obvious realization finally struck me:

I can imagine what it feels like for someone who is brain injured to lose someone or something, to feel disoriented in the world at large, because I can understand it from my own perspective. I can presume to know Lucy in a similar way I can presume to know any other character. I can sympathize with her, and, at my best, I can empathize.

I had been pushing my character, and maybe even my sister, into an “other” box, inadvertently dehumanizing her experience, when what I needed to do instead was bring her into my own head more completely and fold our experiences together. Once I understood this about her, and about me, I finally felt free to explore the inner workings of her emotional world in the same way I had strived to understand her cognitive world.

Trying to dwell inside her mind wasn’t easy. It involved imagined dialogue playing out in my head in countless conversations. I’d write down snippets of discussion I’d imagine my characters engaging in and then have them talk about random topics completely out of context in an effort to discover what they might say and how they might react. I wrote pivotal scenes many times over, imagining Lucy taking any number of different courses of action to uncover the hypothetical results of those actions. Some of these scenarios led to wildly wrong ideas that led her to places that didn’t make sense, but each false turn helped me gain greater insight into her character. When I discovered the emotional truth in any given moment, I would capture it and write the scene around it.

Ultimately, what I gained through forcing myself to try to inhabit some of Lucy’s challenges first hand, both big (love, loss, death) and seemingly small (from cleaning, to navigating the city, to getting up and out each morning), was a whole new level of respect for my sister.

II.

It took me a year or so to build up the courage to tell Caren I was writing about a character inspired by her. I knew by that point that I was writing a book, and I understood that there was no going back. There was just one problem: I wasn’t sure my attempt at a novel was enough justification to probe around my sister’s brain. What if she hated it?

A lot of writers might argue that worrying about your subjects and their reactions prematurely will only derail the artistic merit of the project. Perhaps. But this was my first novel, and if my sister was in any way offended or bothered by the idea of this book, I knew I wouldn’t be able to move forward.

It took me many months to build up the courage to tell her what I was working on. I didn’t ask for her authorization explicitly, but I hoped she would provide it. I talked around the subject for a while, stalling by asking her a bunch of unrelated questions, until finally I blurted: “So what do you think?”

She barely hesitated. “Sounds cool,” she said.

Her understanding was immediate. And once the relief set in, it occurred to me that this project could go deeper. My character drew pictures. Caren sometimes drew pictures. I wanted to involve her in the novel somehow, since she was such an integral inspiration in the first place. So I asked her if she’d be interested in doing some drawings for the book. She hesitated at first, citing fear of extra pressure and an inability to meet deadlines. But slowly she warmed to the idea, and as her enthusiasm for the project grew, so did mine.

As the work progressed, I began to realize that this book was about more than proving myself as a writer, and it was bigger than a hook of using my sister as inspiration. This book presented us with an unprecedented chance to collaborate. While we had always had a strong bond between us, with nine years age difference (she’s older), many miles geographically, and two entirely distinct views of the world, this was our first chance to check in regularly about something unrelated to our lives, to peek into each other’s creative mindsets, and to value one another in an entirely new way.

When Caren began to send me pictures and articles related to content I was writing about, she helped me add depth and texture to my writing—not only with bits of added research, but with moments of insight into her process. In collecting her art for the book, of which nineteen total pictures would appear in the finished novel, I discovered moments when the character and the person blended seamlessly. She would do nothing for months at a time and then all of the sudden a flurry of sketches would come in, complete with coffee stains, creases in the paper, and lost versions of earlier drafts. All of this behavior was true to both Lucy and Caren.

During one of her unproductive periods, I understood that my sister was battling with blocks that didn’t allow her the opportunity to focus. I wished then that I could write her out of these hurdles, and the knowledge that I couldn’t produced an ache. But that longing made my understanding of and empathy for Lucy that much stronger.

III.

I wasn’t ready to let Caren read the book until I’d finished a draft I deemed complete. In the end, it took years. I waited until I had actual interest from a publisher. And at that point, I knew I didn’t have a choice.

After I sent her the manuscript, I held my breath. Would she recognize herself? Would she be bothered by the characterization? What if she hated it?

Once she received the document, it only took her a few days to finish.

“I’m impressed,” she said. “It felt like a real book.”

It was the greatest compliment she could have given me.

We didn’t talk about her experience reading it, which elements stood out to her, any particulars that seemed amiss. In the end, I could imagine how she felt moving through those pages, and that was all I needed.