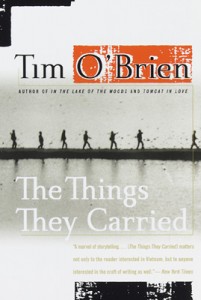

The classic The Things They Carried is being re-released in honor of its 20th anniversary, so unsurprisingly, Tim O’Brien keeps popping up in my radar lately. Besides being a powerful writer, O’Brien is also a great teacher, and in his recent interviews he offers useful thoughts for writers of all levels.

In this interview for Beyond the Margins (with Grub Street program manager Sonya Larson), O’Brien discusses the writing of The Things They Carried, how being a father changed his writing, and recent literary works by soldiers stationed in Iraq and Afghanistan:

I have read a number of books and magazine articles by veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. I’ve read some really, really good ones, and– as there were in Vietnam– there are some really, really bad ones. By and large really great writing from all wars comes a good time afterwards, when a person has had the time to let material develop and form itself, so that it’s not rhetorical. So that it’s not so heavily autobiographical. The great works to come out of World War II, the great American works to come out of it, took years and years. The Naked and the Dead, Slaughterhouse Five, and Catch-22. They didn’t come the year after the war was over, and I don’t think you can expect that with any war.

It’s a bit like writing about cancer; there needs to be time. You need to find a way to transcend the tendency to put in every little detail. Just because it felt so important, it may not be important to the reader. And time is needed for imagination to come into play and to work with the material, to shape a story that may not be wholly in the real world, but only partly. I’ve read some really fine things that have come out of Iraq, and I’m sure even better things will come out in the years ahead.

In an audio interview with MediaBistro, O’Brien chatted about blurring the line between novel and memoir and the need to pay attention to sentences while writing:

Tim O'Brien / photo credit: David Louise Edelman

Something has gone wrong in our schools—it’s sad to see even in MFA programs students don’t know how to make decent sentences. In a lot of cases, I’m talking about grown, 35-year-old students who speak fine English, but for some reason, don’t write it. And students hate hearing that, but I think it’s absolutely essential for success. I don’t mean publishing, but a successful piece of work. […] Just in my case, for a thing to end up any good—that is in its lasting power or lasting in it’s dance of language—requires a thing to sit for awhile on the desk. I think there’s a tendency—at least I have it, when I write emails—to not check our own sentences. That is going to undermine prose.”

And finally, in case you missed it, take 15 minutes and read O’Brien’s essay “Telling Tails” in The Atlantic‘s 2010 Fiction Issue.

But for me, as a reader, the more dangerous problem with unsuccessful stories is usually much less complex: I am bored. And I would remain bored even if the story were packed with pages of detail aimed at establishing verisimilitude. I would believe in the story, perhaps, but I would still hate it. To provide background and physical description and all the rest is of course vital to fiction, but vital only insofar as such detail is in the service of a richly imagined story, rather than in the service of good botany or good philosophy or good geography.

Every writer—emerging or not—should keep this idea in mind.