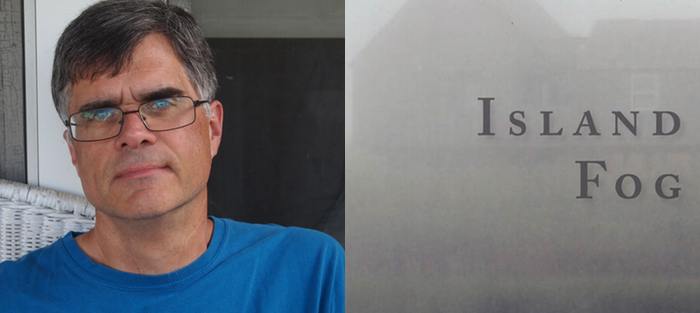

A native of the Washington DC area, John Vanderslice has an MFA from George Mason University and a PhD from the University of Louisiana-Lafayette. After graduating from ULL in 1997, he began teaching at the University of Central Arkansas (UCA), where I met him when I began teaching there in 2004. John is a much-loved professor, and I was at once struck by the wit, the range, and the quality of his short fiction, which has been published in many leading journals, as well as several anthologies, including Chick for a Day and The Best of The First Line. His debut collection, Island Fog (Lavender Ink), was published in the fall of 2014. He is also a marathon runner, and gets up earlier than a fisherman each day to write.

Named by Library Journal as one of the Top 15 Indie Fiction titles of 2014, Island Fog is a quirky yet captivating collection of ten stories and two novellas, set on Nantucket Island, which is both a microcosm and a prism through which the reader catches illuminated glimpses of American life, from the hard, dangerous times of the whaling community to the present-day tony resort of the super-wealthy. The essence of all the fictions is the awful weight of history pressing down upon the island, even in those stories set in a twenty-first century America struggling to reconstruct its identity. The final novella, “Island Fog,” is chilling tour-de-force in which we find ourselves in a place so far from reality that, like its hapless and trapped protagonist, we wonder if we are doomed to play parts in someone else’s fantasies forever. John Vanderslice is a writer of vision and this is a haunting, essential collection.

Interview:

Garry Craig Powell: Could we talk about the format and structure of the collection first? There are quite a few linked story collections that use setting as a unifying factor, starting with Winesburg, Ohio. I wonder if you deliberately set out to write a whole collection set in Nantucket—as I set out to write one set in the Emirates—and if so, why?

John Vanderslice: I did not set out to write a whole collection about Nantucket, but several years ago I did consciously begin a series of stories set there. This was in the early 00s and I was visiting the island, as I had previously, with my wife and her family. From the very first moment I set foot on Nantucket, the place had fascinated me—the topography, first of all, and its quiet oceanside beauty, but even more its history and unique mix of populations. For some reason, however, the idea of writing fiction about the island didn’t hit me until that trip. We only had a week there, and I wanted to germinate as many different fictional possibilities as I could. So each morning I would start a new story, write as far into as I could get, and then put it aside. The next morning I would start a new story, and so on. So I had at least five going by the time I left, with the kernel of another turning over in my head.

As I said, I saw those stories as a set from the very beginning. Of course, I tried to publish the stories individually once I was done with them, and three of them did find their way into print in literary journals. I also tried to market a book of short stories called Island Fog. But in that incarnation only half the stories in the collection were set on the island, because that’s the number of island stories I had. I called that half of the book “On-Island” and the first half of the book “Off-Island.” (These were diverse stories chosen for inclusion because they featured a variety of locales.) Well, the collection received some favourable responses from small presses, but no one bit. So I set the book aside, figuring it just wasn’t going to happen. But then, after a break of several years, my wife and I started visiting Nantucket again in 2011. At that point, because in the interim I had been working on an historical novel and had even started a blog about the subject, I had historical fiction on the brain. It occurred to me that Nantucket, with its immense debt to history, was a natural setting for historical fiction. Once again, I started several stories in the mornings on that trip and left with ideas for another one or two more in my mind. It was only after I’d spent many months developing these stories that I had the idea to bring back the earlier Nantucket stories, combine them with the historical ones, and thus make a complete Nantucket book, an overview of Nantucket history from the 18th century almost to the present day. As soon as the idea occurred to me, I realized how much stronger a collection it could be—and how much easier to market—than a collection that was merely halfway about Nantucket.

As I said, I saw those stories as a set from the very beginning. Of course, I tried to publish the stories individually once I was done with them, and three of them did find their way into print in literary journals. I also tried to market a book of short stories called Island Fog. But in that incarnation only half the stories in the collection were set on the island, because that’s the number of island stories I had. I called that half of the book “On-Island” and the first half of the book “Off-Island.” (These were diverse stories chosen for inclusion because they featured a variety of locales.) Well, the collection received some favourable responses from small presses, but no one bit. So I set the book aside, figuring it just wasn’t going to happen. But then, after a break of several years, my wife and I started visiting Nantucket again in 2011. At that point, because in the interim I had been working on an historical novel and had even started a blog about the subject, I had historical fiction on the brain. It occurred to me that Nantucket, with its immense debt to history, was a natural setting for historical fiction. Once again, I started several stories in the mornings on that trip and left with ideas for another one or two more in my mind. It was only after I’d spent many months developing these stories that I had the idea to bring back the earlier Nantucket stories, combine them with the historical ones, and thus make a complete Nantucket book, an overview of Nantucket history from the 18th century almost to the present day. As soon as the idea occurred to me, I realized how much stronger a collection it could be—and how much easier to market—than a collection that was merely halfway about Nantucket.

In some respects, although Nantucket is hardly a “typical” community in the United States, it strikes me that it does function pretty well as a microcosm of the whole country, particularly if you observe it over more than two centuries. Would you agree? And if so, was that fortuitous or a deliberate technical decision that you made?

That’s a really interesting observation, Garry, because whenever I’m there I’m always struck by how different Nantucket seems. I’m always telling people it’s like visiting an alternative United States. (I had the same feeling, for different reasons, when I lived in southwest Louisiana.) It’s such a small place, first of all, with an absolute sense of what it is and what is wants to look like. And it enforces those notions pretty strenuously. There are strict codes that must be followed when one builds or renovates a house. In terms of paint, only a limited range of colors is permitted. As a result, the island maintains a distinctive, singular look so different from free-for-all ash heap of so many American cities and suburbs. Only one commercial chain—a supermarket chain—is permitted on the island. Every other business there is a mom and pop operation, so to speak. And there are no stoplights. Anywhere. Plenty of traffic circles but no stoplights. So it almost reminds you of driving in the south of France.

That said, Nantucket Island is, and has been for a couple hundred of years, under the domain of the state of Massachusetts. It may seem to be unlike America in many superficial aspects, but finally it can never be free of America. It can’t not be America. Perhaps it ends up being America in a particularly potent, ossified form. Certainly issues of class and materialism abound there, as is increasingly and depressingly true throughout the country. For decades, Nantucket has had the reputation of a rich man’s (and woman’s) summer playground, a place where so many goods are so expensive that you only go there if you can afford not to worry about price. On the other hand, it’s hard to ignore the fact of all the lower-paid “help” from the Caribbean and Western Europe and Eastern Europe that populate the island during the season. It’s also a fact that there is a whole class of people who live on the island year round and who are crucial to helping Nantucket remain a viable, actual community—teachers, librarians, carpenters, real estate agents, journalists—but who struggle to find affordable housing for themselves in a place that so caters to its wealthy summertime visitors.

To be fair to the island, it’s possible that themes of class and materialism come up in a variety of the stories simply because that’s an abiding concern of mine, no matter what I’m writing about. So I found it to write about in Nantucket. But there are certainly aspects of the island that make it easy to write about those themes.

Right. And by the way, you very clearly show how different the place is in the collection. But I noticed that a lot of the prevailing themes in American history—racial prejudice, issues of gender and sexual bigotry, and, as you mention, class and materialism—also come up. I’ll return to that later. The first five stories of the collection, which are grouped under the heading “King Phillip’s War,” are all historical fiction. The second half of the book, six fictions titled “Island Fog,” are all set in contemporary Nantucket. That’s pretty unusual. Can you tell us why you chose to embrace both an historical perspective and a current one? What advantages did that give you?

Obviously, I hit on a lot of this with my answer to your first question. The two different gestation periods for the two halves of the book are reflected in the very different time signatures for their respective stories. When I was working on the contemporary stories I thought of them all as happening “now,” which is why the early 00s all seem bunched up in the second half. But when I was writing the historical fictions I knew I wanted to stretch those out over a wide loop of time, because by that point the whole history of the island had become so fascinating to me. It was just two different conceptions of what I was doing for those two halves. When I put the stories all together to make one book I considered not dating the stories in the second half. Those would simply be Nantucket “now.” But then I realized that too many of the incidental details of those stories depended on the Nantucket I visited in the late 90s and early 00s. The takeover of internet culture (including Facebook, Twitter, and the rest that followed) in the mid-00s as well as the great economic bust of 2007-08 has marked the island in distinctive, lingering ways. In order for the stories of the second half to still ring true to me, I needed to set in stone their dates, just as I did for the stories of the first half. I guess this means those stories are just as much historical in nature as the ones in the first half. It’s just more recent history.

Obviously, I hit on a lot of this with my answer to your first question. The two different gestation periods for the two halves of the book are reflected in the very different time signatures for their respective stories. When I was working on the contemporary stories I thought of them all as happening “now,” which is why the early 00s all seem bunched up in the second half. But when I was writing the historical fictions I knew I wanted to stretch those out over a wide loop of time, because by that point the whole history of the island had become so fascinating to me. It was just two different conceptions of what I was doing for those two halves. When I put the stories all together to make one book I considered not dating the stories in the second half. Those would simply be Nantucket “now.” But then I realized that too many of the incidental details of those stories depended on the Nantucket I visited in the late 90s and early 00s. The takeover of internet culture (including Facebook, Twitter, and the rest that followed) in the mid-00s as well as the great economic bust of 2007-08 has marked the island in distinctive, lingering ways. In order for the stories of the second half to still ring true to me, I needed to set in stone their dates, just as I did for the stories of the first half. I guess this means those stories are just as much historical in nature as the ones in the first half. It’s just more recent history.

In terms of advantages, writing from both historical and contemporary vantage points does force you to really know your subject comprehensively and not just as a tourist. One can write a single short story, or even a couple of short stories, about a place based on a tourist’s familiarity and experiences. But you can’t represent whole decades that way. I’m a researcher from way back, and a lover of history too. The cumulative approach that I accidentally hit upon for the book allowed me, and forced me, to know and understand Nantucket that much better. And for that I’m very glad.

That depth and breadth of vision is very apparent: it’s one of the strengths of the book. To return to the point I touched upon earlier, I notice some recurrent themes in the stories, especially intolerance and prejudice of various kinds—religious and sectarian, racial, sexual—and again I’m curious whether you chose to wrote about those issues because you have a “message” or whether they arose spontaneously. Incidentally I particularly liked the subtle way you treated homosexuality in “On Cherry Street” and “Haunted.” There is absolutely no preaching in the stories—as indeed there should not be in fiction, ever, in my view—and both these stories seem only tangentially “about” homosexuality. They are simply love stories that happen to feature homosexuals. Could you comment?

Yes, sure. Again, those are great observations. To an extent the recurrent themes are intentional and to an extent accidental. And finally, as with the class concerns I mentioned before, they are simply part of my intellectual makeup. I can’t help but gravitate toward them. As for my homosexual protagonists, I don’t think I was thinking of “Haunted” when the plot for “On Cherry Street” occurred to me, but at some point in writing “On Cherry Street” I decided to make a very deliberate connection between the two pieces. By that point I had realized all the Nantucket stories were part of one collection, and I was trying to think of subtle, unobtrusive ways to draw connections. An easy one was to simply have Matthew in “Haunted” live in the exact same house as Orpha in “Cherry Street.” (In fact, I gave “Cherry Street” the title I did in order to make this fact abundantly clear to the reader.) And having made that choice, it meant that the ghost character—if that’s what it is—in “Haunted” could also be a part of “Cherry Street.” I worked the ghost into the historical fiction, although it’s not nearly as central to that story as it is in “Haunted.” I appreciate that you say the stories aren’t about homosexuality; they’re simply stories in which two homosexual protagonists are in love. That’s exactly right. I think it’s really important that stories be “allowed” to feature gay characters without being “about” homosexuality. After all, no one thinks of a heterosexual love story as being “about heterosexuality.”

An important sign that homosexuality has genuinely been accepted in this culture will be when people can write love stories featuring gay characters and they’re just read as love stories. Also, as a heterosexual I don’t know how much I can bring to a discussion of the nature of, or political issues surrounding, homosexuality. I’d rather leave that discussion to others.

In any case I think you’d agree with me that the writer’s job is not to proselytize but simply to portray people in all their complexity, along with their moral dilemmas, and allow the reader to decide what’s right and wrong. Which you certainly do. And I love those subtle connections you make, incidentally. By the way, I consider “Haunted” the most brilliant story in the collection, if we except the novellas. It’s technically fascinating because it’s simultaneously a Gothic fiction and a sort of postmodern take on Gothic fiction. Would you agree? Is that what you were aiming for?

First of all, thanks. Those are high compliments coming from you. “Haunted” is certainly one of my favorites in the book. As for the gothic nature of “Haunted,” in fact, when I wrote that story I wasn’t consciously trying to write a gay story but to write a literary, non-sensationalist, non-cheesy ghost story. I just decided, and I don’t even remember why at this point, to make the character gay. And I didn’t ever feel that making him believably gay was much of an issue. What I really sweated over was bringing in all the supernatural elements in a way that was compelling, believable, dramatic, and yet not clichéd. Like you, I’m a fan of gothic fiction. I think that encounters with the supernatural, whatever they mean or indicate, are a part of the human experience, even if it’s only a matter of humans imagining them. As a part of human experience, it deserves to be represented in fiction. And by that I mean literary, realistic fiction. Can that be done? Well, I tried.

And succeeded, without question. Have you been influenced by the current vogue for the Gothic in pop culture?

I have less than no interest in ghoulish, bloody pop horror fiction and cinema. And even less than that in pop fantasy fiction creatures like warlocks, goblins, and vampires. When, in the twentieth century, writers of realistic fiction gave up the supernatural as a valid subject for treatment, they essentially left it for genre fiction writers to exploit. So much so that for most people these days “supernatural fiction” automatically connotes genre fiction. Once in a while, as in “Haunted,” I try to reclaim the form for literary fiction. I’m certainly not the only literary writer doing so, I’m happy to report. (By the way, there’s a hint of a ghost in the last scene of “Tarry” as well, but I purposefully left that tenuous.) As for “Haunted” as postmodern, I’m not quite sure what to say about that. As you know, many of my short stories can fairly be described as postmodern, but I didn’t have that in mind at all when I wrote “Haunted.” I guess I’d be curious to know how you think it functions as a postmodern take on the Gothic. You might very well be right; I just don’t know what about it earns that description.

Well, there’s a tradition in Gothic fiction of highly rational protagonists who find themselves most unwillingly having to accept the supernatural as real: you see this in some of M.R. James’ stories, for example. But the fact that your protagonist makes his living by giving rather corny ghost tours seemed to add an element of parody that’s usually lacking in the traditional ghost story, and to me hinted at metafiction. I also thought that the punning meaning of the title—the protagonist is both haunted, apparently, at the literal level and also in the more figurative sense in which the word is used when we talk about being haunted by a piece of music or a past experience—this seemed to me to call into question intellectually the very meaning of the word, which a traditional ghost story writer does not wish to do. M.R. James wants you to feel chills down your spine. I don’t think you do. Maybe I’m wrong, but it strikes me that you are pushing us to think and feel more deeply about complex issues. But to go back the whole issue of genre that you bring up, in fact you explore and experiment with various genres in the collection. “Taste” seems straightforward horror, reminiscent of Lovecraft or Poe. “Morning Meal” and “Newfoundland,” on the other hand, are more like what used to be called ‘dirty realism’—Carveresque in their apparently simple and straightforward, yet very subtle, portrayals of disastrous marriages. Were you concerned about having such a wide tonal range in the collection?

Well, there’s a tradition in Gothic fiction of highly rational protagonists who find themselves most unwillingly having to accept the supernatural as real: you see this in some of M.R. James’ stories, for example. But the fact that your protagonist makes his living by giving rather corny ghost tours seemed to add an element of parody that’s usually lacking in the traditional ghost story, and to me hinted at metafiction. I also thought that the punning meaning of the title—the protagonist is both haunted, apparently, at the literal level and also in the more figurative sense in which the word is used when we talk about being haunted by a piece of music or a past experience—this seemed to me to call into question intellectually the very meaning of the word, which a traditional ghost story writer does not wish to do. M.R. James wants you to feel chills down your spine. I don’t think you do. Maybe I’m wrong, but it strikes me that you are pushing us to think and feel more deeply about complex issues. But to go back the whole issue of genre that you bring up, in fact you explore and experiment with various genres in the collection. “Taste” seems straightforward horror, reminiscent of Lovecraft or Poe. “Morning Meal” and “Newfoundland,” on the other hand, are more like what used to be called ‘dirty realism’—Carveresque in their apparently simple and straightforward, yet very subtle, portrayals of disastrous marriages. Were you concerned about having such a wide tonal range in the collection?

Hmmm . . . I can’t say I was concerned about that, possibly because I wasn’t consciously thinking about it. But as you know, I teach a class called Forms of Fiction and I certainly revel in that class. I enjoy challenging the students and myself to try on these various fictional forms; and some of what I write in that class ends up as stories that I publish. If you observe a kind of forms experiment structure to Island Fog, however, it’s less of a case of me deliberately trying out different forms than simply being open to them as a writer. I think that’s just how my imagination works, especially now. When I was in training as a fiction writer, I wrote pretty much straight traditional realism. At that time you couldn’t write short stories in America without being influenced by the example of Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolff and Bobbie Ann Mason, among others. They were simply the kingpins of the era. And that “school” of writing (from what I understand, those writers actually hate to be labelled together as a school, but it is convenient) certainly still influences me and must have influenced some of the stories in the collection, especially the ones I wrote earlier; that is, the stories in the second half of the book. On the other hand, I’ve never been a strict minimalist, even when I was first trying to write serious fiction back in the ‘80s. The literary models I took to heart as a young reader were far more in love with words; I couldn’t love those books and turn out to be a minimalist.

I should say that there is one story in the collection that was partly influenced by my Forms of Fiction class, and that is the very first story in it: “Guilty Look.” Although it’s the first story, it’s actually the last one I imagined and composed. And I didn’t get the idea for it on Nantucket but only after I was back home in Arkansas that fall reading Nathaniel Philbrick’s Away Off Shore, a wonderful history of the European settlement of the island from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. That semester I was teaching crime fiction in my forms class; and since all of the action in my story is precipitated by a notorious (and real life) crime, I decided to begin composing the story while the class was journaling for crime fiction. I didn’t come up with the idea of the piece because of the class, but the class certainly facilitated my finally get started on it.

That’s fascinating. Some writers have argued that teaching stunts their creativity, but you are clearly of the opinion that it stimulates yours. I have sometimes found that too. But let’s move on to “Island Fog,” the novella which lends its title to the contemporary stories and also the book. I suppose that indicates that, like me, you consider it the standout work of the collection?

Yes, absolutely. Of course, it’s not that unusual for a collection that includes a novella and stories to end on the novella, but part of the reason I wanted to put “Island Fog” last is that I loved it so much. Even though it’s been several years since I’ve written it, and I’ve written a ton since then, I think it still might be the best story I’ve ever written.

I have to say that the book is well worth the price of admission for “Island Fog” alone, which in my view deserves to be counted among classic novellas. It reminds me, with its elusive mix of illusion and swiftly changing realities, not so much of Latin American magic realism as of the German fabulist tradition. I am thinking of writers like E.T.A. Hoffman, Heinrich von Kleist, Kafka too of course, the Hermann Hesse of Steppenwolf, and also the Swiss metaphysical detective story writer, Friedrich Durrenmatt. Am I on the right track? What were your influences?

Okay, I feel a little like the magician who is being asked to explain a trick, because in fact there was one incredibly profound influence on the story “Island Fog” and that is John Fowles’ The Magus. I read that novel in the year or two before I wrote “Island Fog,” and when I was working on the story I felt it surge back as a nearly constant influence. I was not trying to copy the novel by any means, but it certainly provided a crucial literary model. In a general sense, my story is similar to Fowles’: a young man who has not quite found himself yet moves to an island where he meets an imposing, inexplicably omniscient person, who seems to have the power enact physical changes that are impossible to explain. This person controls, virtually rules, the life of the young man who, thrown into the middle of it all, doesn’t have time to figure things but must just roll with it, adapt on the fly. That said, there’s no one particular detail about my story that I feel is explicitly derived from The Magus. I think Fowles’ contribution (and it was absolutely vital) was to “permit” me to push the bizarre phenomena in my story as far as I could take them. In fact, in a way I push farther than Fowles does. In the end, The Magus devolves, if you will, into a semi-realistic explanation for everything the main character sees and experiences in the novel. And by the end the character has escaped back to real life. There’s no such out for Doug in my story, and he’s never given an explanation for what he sees. I guess those aspects of the story do push it more toward the fabulist and writers like Kafka. But it wasn’t them I had on the brain, just Fowles.

Funnily enough, I had thought of The Magus—I think I just didn’t mention it because it didn’t fit in with the German group. I can certainly see the similarities, and differences, that you mention. On one level, like “Newfoundland,” “Island Fog” is a story that seems to criticize our shallow, consumerist culture, and perhaps suggests that in the modern media landscape, where “reality shows” are so pervasive, we can no longer distinguish between fact and fiction, and almost all of us find ourselves acting roles, whether we are aware of it or not. Am I going too far? Doug’s nightmarish discovery that he is unable to resign from his job, perhaps ever, definitely has a Kafkaesque echo, and seems to indicate that your vision of contemporary America is terrifying: that this potential paradise has become a sort of existential hell.

Funnily enough, I had thought of The Magus—I think I just didn’t mention it because it didn’t fit in with the German group. I can certainly see the similarities, and differences, that you mention. On one level, like “Newfoundland,” “Island Fog” is a story that seems to criticize our shallow, consumerist culture, and perhaps suggests that in the modern media landscape, where “reality shows” are so pervasive, we can no longer distinguish between fact and fiction, and almost all of us find ourselves acting roles, whether we are aware of it or not. Am I going too far? Doug’s nightmarish discovery that he is unable to resign from his job, perhaps ever, definitely has a Kafkaesque echo, and seems to indicate that your vision of contemporary America is terrifying: that this potential paradise has become a sort of existential hell.

Well, contemporary America is, in my mind, an existential hell, yes. As I heard someone say recently on Facebook, “Classism is the new racism.” It’s okay to despise the poor and blame all their troubles on them, while at the same time trying to grab as much as you can for yourself by whatever underhanded means possible. This isn’t tacky and immoral behavior; it’s the new national credo. You’re nobody unless you’re megarich. Our government endorses this point of view through a painfully regressive income tax system. It’s literally sick. And to complain about it is to be called un-American. Thus, millions of people willingly submit themselves to the tyranny of the rich. And here I thought America was supposed to be about resisting tyranny. Silly me.

But that’s my worldview. And my worldview, while a part of who I am, isn’t necessarily what I’m consciously trying to play out as I compose fictions. Finally, fictions are about the individual characters inside them, and you better hope like hell that those characters are interesting enough for readers to pay attention to. So, in short, I’m agreeing and disagreeing with your premise. My worldview surely must come out through the cracks of my fiction, but that’s not quite the same as saying they represent the themes of my fiction. As for Doug’s inability to quit his job, I think that just struck me as the most helpless, nightmarish position any working person could ever be put in. It’s one thing to hate your job; it’s another thing to realize that you can never leave it. Literally never. Ouch! Talk about feeling trapped. And, besides, it seems to me the only way that particular story can end. Doug’s options are closing down from the very start of the story, and they continue to close down throughout. The only logical end for the story—sorry, Doug—is for him to run out of options altogether.

At another level, you might say that the entire book is about The American Dream. It’s very clear in the earlier stories that in spite of the hardship of the characters’ lives, they feel themselves to be free, to have agency over their own lives. They strive and struggle, and some of them are very successful. Everyone seems powerful. And yet in the later stories, ironically, although many of the characters are wealthy and privileged, there’s a sense that people are no longer in control of their lives, that they are mere cogs in an absurd machine—what Cocteau called La Machine Infernale. There is no escape. We are like Jim Carrey’s character in The Truman Show. It’s possible that I am superimposing my own worldview on the collection, but I don’t think so.

Again, that’s a really insightful observation, but due to the accidental nature of the book’s structure, and the way in which it was composed in two separate periods years apart, I can’t say that I deliberately intended the book to carry the kind of arc you describe. The other thing is, while the characters in the first part of the book clearly believe they have agency over their own lives, and act as if they have agency, the facts don’t always support their confidence. Pease, at the end of “Guilty Look,” is arrested. The narrator of “King Philip’s War” is wounded, perhaps fatally. Orpha in “Cherry Street” finds herself, in that last scene, trapped by news she could not have anticipated and certainly would not have wished for. Gideon Mitchell is simply unable to overcome his lust for human flesh; and the teacher in “Tarry” realizes that the island culture is opposed to her in most direct and nefarious ways that she would have previously guessed. She can’t seem to fathom why she still lives there, except that Nantucket is all she has ever known. So while I hate to say it, I think the facts of the book suggest that we are all trapped; and any independence felt by anyone anywhere at anytime was and is an illusion. It’s for that reason I thought the quote from Beckett made such a nice epigraph for the book: “We may reason to our heart’s content, the fog won’t lift.”

Very apposite, definitely. In any case, it’s a thought-provoking, far-ranging collection that deserves to be noticed, reviewed and read. I hope it is successful. And thank you for speaking to me.