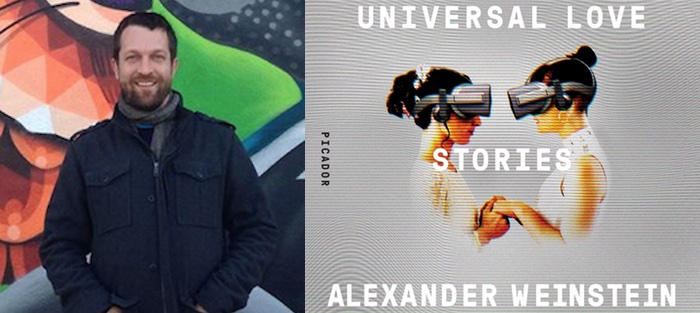

I met Alexander Weinstein at the Creative Writing Innovative Pedagogies Symposium at the University of Central Missouri in 2015. While most writers, even young ones, have a blasé or even cynical air, Alexander was someone whose eyes seemed open to wonder, maybe even joy. And when his first book, Children of the New World (Picador, 2016) came out the following year, I read it, loved it, and adopted it for a course I was teaching at the University of Central Arkansas. My undergraduate students loved it, too: in fact, I had never seen such enthusiasm over any book I had taught. The collection was also one of the New York Times’ 100 Notable Books that year, and in the round-up the Editors summarized it as follows: “The terror that technology may rob us of authentic experience — that it may annihilate our very sense of self — is central to this debut collection of short stories.” Quite. I had never been a fan of speculative fiction, but this was unlike anything in the genre I had ever read.

Born in Brooklyn, Alexander Weinstein attended Naropa University for his BA degree, and earned an MFA from Indiana University in 2008. Among his many awards are NPR Book of the Year 2016, inclusion in Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Reads 2016, and Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2017 (for the story “Openness”) His latest collection, Universal Love (Henry Holt, 2020), now available in paperback (Picador, 2021), is every bit as terrifying, as funny, and as thought-provoking as his first. Weinstein is a professor of Creative Writing at Siena Heights University and Director of The Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing.

Interview:

Garry Craig Powell: Your website describes your latest book, Universal Love, as “a hypnotic collection of speculative fiction about compassion, love, and human resilience in the technological hyper-age.” While I agree that the stories have those underlying themes, it’s also true that they offer a harrowing vision of what the near future may hold for us, as did your last book, Children of the New World. On the whole, it’s a dystopian society that you’re depicting, isn’t it?

Alexander Weinstein: There’s definitely a core of pre-and-post apocalyptic landscapes running beneath the surface of all the stories in Universal Love. Many of my stories take the dystopian times we’re presently living through (for example, a culture where we have dating apps that encourage us to swipe people into the trash) and extend them to their plausible and more worrisome futures. The result is that my predictions seem to keep becoming reality! No sooner had I written “We Only Wanted Their Happiness,” wherein children are begging their parents for cybernetic implants, than Elon Musk publicly announces his work on Nerualink brain implants. So, my hope is that these stories might give us all pause long enough to jump ship from the cybernetic Titanic we rushed aboard.

According to Publishers Weekly you are “Channelling Ray Bradbury with contemporary allegories.” Do you agree? Is he an influence? How about other canonical science fiction authors? I wonder in what ways you see yourself as writing within that tradition, and to what extent you see yourself as departing from it.

Interestingly enough, I’ve never been a big sci-fi reader. Bradbury was an influence when I was a kid, but mostly through a television show called The Ray Bradbury Theater. Spielberg’s Amazing Stories TV series was probably an even bigger influence. I was also reading a lot of Stephen King from 3rd to 10th grade. So, I think the fantastical was always there as a background aesthetic. But I felt like I never knew enough to be a true Sci-Fi writer. The feeling for me was that it was a specialized genre which demanded high scientific knowledge (hard sci-fi), and I often found the writing too technical when I tried to read it. I felt the same about high fantasy, which also had a lexicon that I felt an outsider to. It wasn’t until my thirties that I read Tolkien, and I loved it, but it was late in my development as a writer.

Interestingly enough, I’ve never been a big sci-fi reader. Bradbury was an influence when I was a kid, but mostly through a television show called The Ray Bradbury Theater. Spielberg’s Amazing Stories TV series was probably an even bigger influence. I was also reading a lot of Stephen King from 3rd to 10th grade. So, I think the fantastical was always there as a background aesthetic. But I felt like I never knew enough to be a true Sci-Fi writer. The feeling for me was that it was a specialized genre which demanded high scientific knowledge (hard sci-fi), and I often found the writing too technical when I tried to read it. I felt the same about high fantasy, which also had a lexicon that I felt an outsider to. It wasn’t until my thirties that I read Tolkien, and I loved it, but it was late in my development as a writer.

My initial influences came much more from literary realism and, later, the speculative genres. I read Baldwin, Chekov, Kafka, and Maugham early on. Then in high school I read Tom Robbins, whose rule-breaking exuberance blew my mind. I didn’t know you were allowed to have fun as an author! His work led me to Vonnegut, and soon to Ishmael Reed, George Saunders, Karen Russell, Italo Calvino, Borges, Murakami, Woolf, Kelly Link, Steven Millhauser, Tatyana Tolstaya, and many other literary experimentalists. Ultimately, it’s this literary experimentalist tradition that I’m writing in, though I’ve been thrilled and deeply honored to find that the sci-fi and fantasy communities have embraced my work so readily.

One of the obvious weakness of a lot of science fiction, at least to me, is that it’s plot-driven, or idea-driven, or both. I’d say that’s true of Bradbury, Ballard, and Asimov. On the other hand, one feature of your work that I admire is that you create vivid characters who are deeply and convincingly human–even when, at times, they’re robots, as in “Childhood.”

Yes, exactly, it’s this plot-driven/idea-driven issue that I’m speaking of when I find myself pulling away from certain sci-fi. As a writer, I never want to preference my ideas (even though they’re the core of what generates the story). While my stories have wild landscapes and technological premises (for example the robotic adopted children in “Childhood” who have learned to smoke their own emotion chips), that premise is always backgrounded so that the human emotions and conflict can take the lead. It’s in the hearts of the characters that make the stories truly come alive. So, in “Childhood,” I had to dive into my own worries about drugs and teenager addiction, which meant feeling into my fears as a parent raising a teenage son. I also had to try to remember what it felt like to be a scared twelve-year old boy who simply wanted love. It was a mix of these emotions that I gave to the robotic children in that story, and why they eventually became as alive as humans.

Another strength of your writing is your world-building. Specificity is a vital component of this, isn’t it? I’m thinking of stories like “Beijing,” which don’t just tell us how polluted China is in the near future, but show us, and not just visually. I found myself practically gasping for breath when I finished reading that one. Could you tell us how you achieve that kind of sensory plausibility?

It’s wonderful to hear you were gasping for breath—because I wanted the reader to feel the smog in the air, to feel the choking fumes, to even gasp a bit as they read the story! Not because I’m a sadist, just because I believe we become motivated for changing the world when we’re somatically affected. For me, that bodily impact came from being in Beijing, where my phone was warning me that the air was unbreathable on some days (one of the most dystopian iPhone weather messages I’d ever seen). My eyes were watering, the yellow smog lay over the city, swallowing apartment buildings in its pale beige clouds, and I wondered: How could we have constructed a society that could be this poisonous?

It was that gut reaction that drove the writing, and as I wrote, I used a lot of techniques that I’d learned from reading Baldwin’s story “Sonny’s Blues.” Baldwin is a master of motif, and that story has this cold ice and murky light which repeats throughout the story. He achieves this by layering in the shadows of these words again and again, a kind of circular pattern of masterful repetition that ultimately embeds the motif within the setting. This was what I was aiming for in my own work: to weave the scenic details in a way that ended up immersing the reader in the world.

In January this year, you published an essay on LitHub called “What Gods? On Writing Spirituality in Literary Fiction.” It caught my attention strongly, partly because I once wrote an essay on the same topic myself, and made some similar points. Like you, I think the sacred is largely absent from contemporary literary fiction, though that wasn’t always the case. Why do you think so few writers take on spirituality in their books? Because they’re materialists, or are they afraid to broach the subject? You mention the unspoken bias against spirituality in your essay, which is something I’ve noticed too. It often seems to be considered reactionary, backward, and superstitious, doesn’t it? As you say, it seems that we can only touch the subject at all with irony and sarcasm.

I think part of the answer is that most Westerners have been so thoroughly indoctrinated in the gospel of scientific materialism and philosophical rationalism that it creeps into even our art. When I was writing that essay, I found myself constantly walking up to an edge that seemed perilous as an author. Was it okay to say I believed art could function as medicine? Or that the unseen spirit world was as legitimate a reality as Chicago? For that matter, if I admitted I actually believed in fairies or the presence of unseen Gods, would that forever delegitimize me as an author (and an “intelligent” human being) in the eyes of Western Literature?

Beneath the negative bias toward spirituality is a deeply colonialist ideology. I know a lot of progressive, well-educated, socially-aware, and academically-trained individuals who kind of lose their shit when spirituality is mentioned! These are people who’d be quick to espouse a philosophy of multiculturism and the importance of respecting all ways of life, but secretly (and not so secretly) they harbour a rather awful perspective regarding the indigenous spiritual cosmologies of the world. There’s a sense that: Well yes, we must respect the world’s people . . . ahem . . . but you don’t really believe in such nonsense as chakras, chi meridians, and shamanic healing do you?

What strikes me most, though, is that when you really get down to speaking with people about their most significant and transformative experiences (whether that be through love, or parenthood, travel, or psychedelic experiences) almost everyone has had contact with a transcendent dimension of consciousness, a world that intersects again and again with the sacred, a life filled with awe and wonder. My hope is to be able to lend my voice to the idea that it’s okay to begin speaking more openly about these realities, for they are sacred aspects of our life that deserve not merely dignity but celebration in our literature.

And there are, of course, exceptions to this general anti-spiritual stance. George Saunders is one. How does he manage to do it without being scorned? Is it because he’s a Buddhist, which is considered a cool religion? Or because he’s rather ironic himself? What about you? Have you been criticised for taking on spiritual themes?

Saunders is a wonderfully heart-centered writer and his stories sing with grace and compassion, which I think are excellent approaches to spirituality. Buddhism in general tends to have a very human-centred, non-dogmatic approach, particularly in how it’s been assimilated and taught in the West, and so I think it has been more widely embraced as an “okay” spirituality to practice and has gained legitimacy over the past couple decades.

Irony, as you point out, does play a part, at least I can see that in my own work. Not to treat spirituality ironically, but rather to have ironic elements within the humor itself. On one hand, irony works as a marker of critical thought—to be able to see something ironically means that you’re able to observe it from a meta-level which is removed enough not to be subsumed by the subject. In short: we want to know that our author is able to see the larger picture. And I think this is what we generally want from anyone giving spiritual teachings as well. There’s an importance in knowing that a spiritual philosophy/teacher has as much room for talking about suffering as they do for bliss. It’s probably why I’m so wary of new-age movements which shy away from addressing emotional pain and become too bliss-based. They seem to lack ironic self-awareness. Then again, perhaps this is simply my own limitations on the bhakti yogic path!

But there’s a difference between irony and cynicism. And I think the cynical approach is to be cutting or snarky about spirituality in literature. And, more broadly, to shy away from vulnerability or spiritual themes in our work. I’ve become increasingly interested in creating short stories that sing with joy, for example. Where is the ode in fiction? After all, we are often overjoyed from love in our lives, or from watching our children come running to us with open arms; we experience erotic bliss, or simply are able to be deeply grateful for this life. These are deep, legitimate, and healing emotions. Why then can’t a short story carry this one note? We might argue that it becomes too monotone, however writers can carry the cynical, weary, life-sucks voice for an entire story/novel and be praised for it! So, I think there’s something about shying away from true vulnerability that’s at the heart of some this dilemma.

Theme is an essential aspect of craft, but also one of the hardest ones to discuss intelligibly, maybe because it’s nearly always implicit. I’d like to hear how you integrate spiritual themes into your stories–if you consciously start off with a particular theme you’d like to explore, and plan the story around it, or whether those themes simply arise naturally from the characters and their conflicts?

Much of this has to do with what we’ve been exploring here—this issue of vulnerability and opening yourself to awe. In many ways, you can’t fake spirituality in fiction. Otherwise you end up with a kind of Hallmark version of mysticism, and the reader knows it immediately. So this is a huge challenge, because essentially you have to be in the very state that you’re trying to capture if you’re going to successfully incorporate the mystical into your writing. It’s not like Googling pictures of a city you’ve never seen in order to write about it; it’s a thousand times more challenging since spiritual realms are metaphysical and require immersion within. It’s precisely what you mention in your essay: it’s hard to write an enlightened character if you’re not actually enlightened. And Googling some photos of auras and chakras isn’t going to cut it!

So, part of the work is constantly allowing my own vulnerability to come forth on the page. This means risking everything I hold in my heart: my fears, my joys, my secret hopes and regrets. It’s the ache of watching my son packing up to get ready to go to college and remembering how his small hand once gripped mine as we waited to cross the street. This wells up the tears inside my voice, which is then a gateway to deeper intimacy with the reader. And this vulnerability is part of the practice of what I’m referring to as spiritual literature. Finally, there’s certainly something Buddhist/Taoist in how I approach conflict. This has to do with not getting caught in the melodrama of ego inherent in classic, conflict-driven literature. I remember watching a hysterical parody of The Glass Menagerie in college, where rather than glass figurines they’d replaced this emotionally-fraught prop with glass swizzle sticks (for cocktails). The result was hysterical, because there was this belaboured melodrama about Laura’s beloved glass swizzle sticks! The effect of the comedy was that we were freed from the plays’ melodrama which we’d been so caught up in. This is part of the Buddhist practice, to free oneself from the world of illusion with a slight smile, and I think a literature of transcendence keeps this ideology at its core.

Could you give any examples of a story that has a spiritual theme even if it’s not at once apparent? (I could, and will—but I’ll be interested to hear what you say first.)

I’m so interested to hear your recommendations here, as I’m always on the search for stories/novels that fall into this category. Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics is one of my favorites—it has such a wonderful Commedia dell’arte humor beneath it. Steven Millhauser’s stories create deep awe and wonder that leave me speechless. Kevin Brockmeier’s stories are beautiful and deeply heart-centered. Certainly Herman Hesse’s work comes to mind. Tom Robbins is openly spiritual in his themes, and Victor Pelevin and the New Sentimentalism movement is also inspirational to me. But I’m all ears, who are you reading/thinking of?

I actually meant in your own work, but since you took me to mean other writers, and your examples are great (I particularly like Kevin Brockmeier’s), I’ll mention a couple. I was thinking about work that is ostensibly about a wholly sterile, materialistic world, that by highlighting that sterility may open the reader’s eyes to a more spiritual dimension. Kundera, Hermann Broch, Stefan Zweig. I tried to do it in my own collection, Stoning the Devil, as well. But let’s get back to how this transcendental realm is evoked. In the LitHub essay, you declare that “the fairy tale author . . . must spend a long time wandering in the fields and groves and resting by the rivers and brooks beneath willows and arching trees.” Hear, hear. What advice would you give to a fiction writer who wishes to share a story from what you call ‘an unseen world’? You studied at Naropa University, a Buddhist institution, and also have spent a lot of time with shamans. Is that necessary?

There’s so many paths to the mystical. In fact, one of my favorite Ram Dass lectures is a story he tells about his early days. He’d just come back from India and meeting his guru, and he was telling this group, of mostly young hippies, very far-out stories about LSD, and meanwhile there’s this one older woman with sensible shoes and a hat with little fruits on it and a large leather purse—in short, someone who seemed totally unlike the scene—who was sitting there nodding along to everything he said. So, Ram Dass gets wilder with his stories, going as far into the realms of spiritual consciousness as he can, and the woman just nods knowingly. Finally, at the end of the lecture, he seeks her out to ask: “But how did you know about all the things I was talking about?” and she leans in conspiratorially and whispers, “I crochet.”

It’s a great story, and I think it highlights just how many paths to spirituality and the unseen world there are. Sacred ceremonies, mediation, yoga, immersing ourselves in nature, and surrounding ourselves with other people who are on the spiritual path are excellent ways to cultivate the very storylines of sacred writing. And I’ve been fortunate to have studied with indigenous tribes who’ve carried the sacred practices of plant medicines, sweat lodges, sundances, and other spiritual ceremonies into our current world. I’ve also been fortunate to have worked with really excellent ceremonial leaders and elders.

The key is to engage with ceremony respectfully as well as consciously. I mention this, because shamanism has become a marketplace item over the past decade, and there are a lot of pseudo-shamanic ecotours setting up ayahuasca ceremonies in South America which cater to a kind of techno-hedonism and modern-day spiritual hunger. There’s also a lot of young, white, DJ-psychedelic warriors our there creating their own makeshift ceremonies which can be filled with unconscious shadows and unsafe practices. For example, there’s been rampant sexual abuse and dark manipulative practices happening in ayahuasca circles, and this is an example of why simply running out to find a shaman or taking plant medicine isn’t the answer. Otherwise it becomes a kind of spiritual materialism that, at its worst, is exploitative of the ecosystem, damaging to individuals participating in the ceremony, and most importantly destructive to the indigenous communities who are trying to sustain their spiritual lineages. So, being very conscious about spiritual practice is vitally important.

In the same essay, you remark that “Beneath the robots . . . and virtual reality landscapes of my fictional worlds, are stories of the sacred.” An example you give is “The Year of Nostalgia,” which revealed to you a truth about the mystery of your own parents. I wonder if you could elaborate on that–without giving us any spoilers, if possible!

In “The Year of Nostalgia,” the main character helps her father deal with grief (and her own grief) by creating a holographic replica of their recently departed mother. The crux of the story is how she begins to learn so much more about who her mother really was through the use of artificial intelligence. This is the technological fun of the story, but what I’m really writing about is how little we often know about those we deeply love.

I’m entering my forties now, and I’ve been becoming increasingly aware of how little I actually know my parents as human beings (rather than simply as “my parents”). My parents and I have a very deep love for one another, but there’s also many ways that I don’t fully know who they are, what their dreams were, what their innermost hopes and regrets have been. So, I’m starting to ask those questions, and to connect with them even more deeply. And I think this is the main realization that my story of holograms illuminated for me: how easily it is to take those we love for granted, and by doing so, how we end up creating our own kind of holograms of who they truly are.

Despite some of the optimistic things you’ve said about humanity, it strikes me, perhaps because I’m a curmudgeonly Englishman, that we are more tribal than ever. I see intolerance and hatred on the increase everywhere, and not just on the far right, where I used to expect it, but recently on the left too, which has surely become far more illiberal. We don’t want to delve deeply into politics here, but—assuming you agree with me—how does the current polarization affect fiction writers? Are you still optimistic? And do you think you have any role to play in the culture wars with your work?

The Trump presidency was one of the most monstrous eras I’ve ever lived through. It was a constant onslaught of racism, misogyny, homophobia, anti-immigration policies, environmental destruction, and it emboldened really horrific elements within our society. I was stunned as a writer. How could I write anything more dystopian than the world which was already being created daily? “Sanctuary,” from the collection, was an attempt to write into the awfulness of that era.

But, of course, there’s the counter to the horrors: the rise of Black Lives Matter and MeToo movements, the demand for human rights and justice, and increasing environmental activism. During the pandemic, alongside the most awful aspects of human selfishness (hoarding hand sanitizer, fist fights over toilet paper, and mask-less pseudoscience) there was also an incredible amount of love and unity. I think about that video from Italy of a trumpet player doing a solo of “Imagine” whose notes cut right through my sorrow and fear to my heart. I think of all of the Zoom calls we’ve made just to tell someone: I miss you, I love you, I can’t wait to see you again. These are testaments to the beauty of this civilization and the dignity of our hearts. We have been through deep trauma collectively, and if we tap into our need for connection and use it to transform our culture to one of unity, love, and healing, we’d be taking an incredible step toward our spiritual growth.

So, yes, I am an optimist at the core, and this is the very heart of my stories, and of the role I believe fiction can play. For the stories in Universal Love speak to hope again and again. Beneath the malfunctioning robots, or the dystopian-Tinder apps, or the cybernetic disconnection, are stories of love, of human resilience, and of our potential to work together to make this world a more beautiful and loving place.