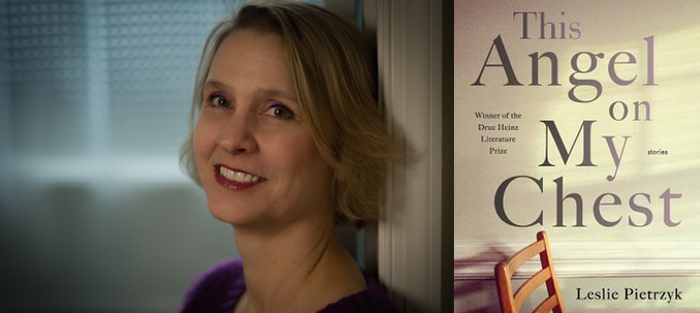

Grief comes in many forms. So do short stories. In Leslie Pietrzyk’s short story collection, This Angel on my Chest, winner of the Drue Heinz Literature Prize and published in October by University of Pittsburgh Press, grief is illustrated through a list, a quiz, a craft lecture, micro fiction, an index, traditional stories, and a YouTube video. These sixteen stories are a force of form that bends your heart to the edge of breaking, just like grief.

Leslie is a member of the core fiction faculty at the Converse low-residency MFA program and teaches in the MA Program in Writing at Johns Hopkins University. She is the author of two novels, Pears on a Willow Tree (Bard, 1998) and A Year and a Day (William Morrow, 2004). Her stories and essays have appeared in Gettysburg Review, The Sun, Shenandoah, Iowa Review, and other literary journals.

Following Leslie’s reading at the Politics and Prose Bookstore in Washington, D.C., we met up at a DC literati book party in her honor at Mary Kay Zuravleff’s house hosted by Carolyn Parkhurst and Paula Whyman. The celebration theme was organized by part of the title story, “Chapter Ten: An Index of Food (Draft),” which catalogs food memories and a dead husband’s favorites: pizza, malted milk balls, and booze. A shot glass etched with the book’s title was gifted to each guest. The party, like This Angel on My Chest, was a eulogy for a love lost, an homage to a heart that can hold more, and a celebration of short stories that illustrate the capacity for both.

Interview:

I want to start, Leslie, with the same question I asked at the microphone during your reading. You’ve taken all these wonderful risks with form. How does the form serve the book?

From a writing standpoint, I know that turning to form helped me create some mental distance that—strangely—allowed me to get closer to the emotional truths I hoped the book would convey. I wanted the words of this book to look different on the page, so that even a casual flip through might unsettle the reader a bit, startle her out of her comfort zone. I also found that using form was a way to add humor and playfulness to what might seem like a totally depressing subject matter: the death of a loved one.

How did you balance all the forms in your organization of the collection as a whole?

There are some stories that didn’t make the final cut: the experiment failed! Other stories were more traditional but were also excluded from the final manuscript. So the selection of stories was important for me as well as their exact arrangement. I needed to signal early on that there would be some experimentation (so the first story is a list told in the second person) but I also wanted to reassure a nervous reader, which meant that a traditional (though short) story immediately followed. As I put together the collection, I kept asking myself what the role of each story was, what it accomplished in the bigger picture, and once that was my question, it became easier for me to see where I might have been repeating myself…and when it was time to yank something out.

There are some stories that didn’t make the final cut: the experiment failed! Other stories were more traditional but were also excluded from the final manuscript. So the selection of stories was important for me as well as their exact arrangement. I needed to signal early on that there would be some experimentation (so the first story is a list told in the second person) but I also wanted to reassure a nervous reader, which meant that a traditional (though short) story immediately followed. As I put together the collection, I kept asking myself what the role of each story was, what it accomplished in the bigger picture, and once that was my question, it became easier for me to see where I might have been repeating myself…and when it was time to yank something out.

Can we talk about the heckler? Was that the first time you’ve been heckled at a literary reading? To be fair, he did proclaim your brilliance and beauty.

[Laughter.]

I believe this was a first, though I will note that apparently he was listening carefully as his first outburst—“Spirits!”—came as I was reading the list of forty-something specific liquors that are mentioned in the book (in “An Index of Food”). Later, I found out that my husband shushed him, and that the guy had a bottle of his own favorite spirit tucked in a coat pocket. While I’m delighted to be proclaimed brilliant and beautiful, even by a drunk heckler, there was immediate tension in the audience, so I thought a bit of humor might be in order. Plus, living in the Washington area, I know the politician’s trick of answering the question you WANT to, not necessarily the one asked, and I was able to talk enough that he got bored and wandered away midway through my answer.

You handled the heckler with style and grace.

Thank you, though I still feel slightly bitter that he didn’t even buy a book!

That does seem stingy.

At the reading you also mentioned the power of memory and the limitations of memoir. Did you always know you’d write fiction about the death of your first husband, Robb, and your widowhood?

I knew I would never write a memoir. I feel my life is too boring to write about without fictional embellishment or without a very low word count. Also, I like hiding behind fiction’s anthem, “I made it up!” While I suppose part of me always wondered if I might write about Robb in that general way in which writers often turn to their lives for inspiration (or exploitation, if we’re being less kind), it seemed like a daunting, scary project. And I had written about him already, secretly, in my novel A Year and a Day, which is about a 15-year-old girl whose mother has committed suicide. Though the book is set in Iowa, in the 1970s, and has nothing to do with husbands or widows, it’s a book directly about grieving, since the action follows the year after Alice loses her mother.

And your other novel, Pears on a Willow Tree, similarly documents domesticity in a novel in stories through the lens of mothers and daughters. Is there a common thread? What’s the tale you find yourself telling again and again in your work?

I think that has been a common theme in my published novels, the tangled relationship between mothers and daughters. I don’t know if I’m finished with mothers and daughters—such fraught, rich material, obviously—but I may be expanding the tale into asking questions about how we come to know other people, and fail to know them; how we know ourselves, and often fail that as well.

I think that has been a common theme in my published novels, the tangled relationship between mothers and daughters. I don’t know if I’m finished with mothers and daughters—such fraught, rich material, obviously—but I may be expanding the tale into asking questions about how we come to know other people, and fail to know them; how we know ourselves, and often fail that as well.

The YouTube video of “One Art” was a craft class in both storytelling and story performing. The text, of course, is a stand-alone story in the collection, but the accompanying video adds another dimension of the reader’s experience. How did you learn to present your work in such a powerful way?

If you mean the performance aspect, I confess to being very involved in high school drama. It’s fortunate that having that experience early on means no stage fright and being comfortable in front of most audiences. I say “most” here because taking on live story-telling, as in the video, was extremely challenging, akin to stand-up comedy, I imagine, where judgment is swift and possibly severe (standing up to talk in front of a bar of drunk people…what could go wrong?). But I’m a fan of The Moth and have admired how the simple act of telling a true story could resonate so powerfully, and I longed to try my hand. I happened to meet S.M. Shrake at a book party as he was founding DC’s Story League, a story-telling organization open to newcomers. He even held some workshops on story telling which were enormously helpful. No notes was terrifying, standing all alone at a microphone was terrifying, telling the truth was terrifying, having a strict time limit was terrifying…yet it was one of the most fulfilling nights of my professional life.

Tell me a little about publishing with University of Pittsburgh Press. What made you decide to enter your collection for the Drue Heinz Literature Prize?

I’ve been familiar with the Drue Heinz Literature Prize for years, and in my mind, it’s the best of the short story manuscript contests: no entry fee, excellent publisher attached to the prize, rigorous and ethical manuscript evaluation, and, of course, $15K for the manuscript. After several months of NYC publishers telling me my book was “too sad” and that they couldn’t deal with short stories, I spent a year entering the top fiction contests. The same basic manuscript was a semi-finalist twice, rejected four times, and won the contest I would have selected as the one I wanted most! I share this in an encouraging way: cast a wide net and accept that there is always subjectivity to the publishing biz. I could not be happier with my happy ending for this book, which came fittingly in December, at the end of my year of contests.

What books influenced you during your writing process?

There were two books in particular that I reread as I embarked upon the journey of shaping a book manuscript out of the random stories I was writing. The first was The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien, the modern classic about the Vietnam War that blurs fact and fiction and seeks an emotional truth deeper than factual, literal truth. The other was Ernest Hemingway’s first collection of short stories, In Our Time, which seems to be on the surface about a young man coming of age in Michigan. Interspersed with the stories are chilling flashes of incidents from World War One, the true subject of the book. Both books were, in my opinion, working to approach dark, difficult subject matter unconventionally; both authors invented a way to tell their stories, which is what I felt I needed to do to make this book come close to the book in my head.

You call the book unconventionally linked stories. Were there any unconventional influences you turned to during the writing process?

Linking these stories by incident was something I struggled with, how to make that structure work. I listened to Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run album quite a bit, having read that he envisioned the action taking place on one summer night. Pet Sounds by the Beach Boys was another influence as I worked to put the stories in conversation with each other. Mark Rothko is one of my favorite artists, so I pondered how it is that his work is essentially the same (two rectangles) yet each piece feels utterly unique…and why the experience of encountering several paintings together is expansive rather than repetitive. I read many villanelles, often called a poetic form of obsession, because I wanted to understand how to create in my book an undercurrent of obsession through repetition. Finally, underlying every project I take on is my appreciation for the “tin foil shrine” housed in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, a mysterious and glorious work of visionary art that James Hampton worked on for fourteen years in a garage; it was found after his death. Making art is an obsessive act, and in the midst, one must separate the creative energy from the anticipation of the audience, I think.

Linking these stories by incident was something I struggled with, how to make that structure work. I listened to Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run album quite a bit, having read that he envisioned the action taking place on one summer night. Pet Sounds by the Beach Boys was another influence as I worked to put the stories in conversation with each other. Mark Rothko is one of my favorite artists, so I pondered how it is that his work is essentially the same (two rectangles) yet each piece feels utterly unique…and why the experience of encountering several paintings together is expansive rather than repetitive. I read many villanelles, often called a poetic form of obsession, because I wanted to understand how to create in my book an undercurrent of obsession through repetition. Finally, underlying every project I take on is my appreciation for the “tin foil shrine” housed in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, a mysterious and glorious work of visionary art that James Hampton worked on for fourteen years in a garage; it was found after his death. Making art is an obsessive act, and in the midst, one must separate the creative energy from the anticipation of the audience, I think.

Are you writing something new now?

I’ve recently finished revising a novel, so now I’m out in Queryland, looking for the right agent. Though highly fictionalized, that novel was also based on something from my own life and was emotionally challenging for me to write. The next book, the one dancing around inside my head, has absolutely nothing to do with my real life…whew!