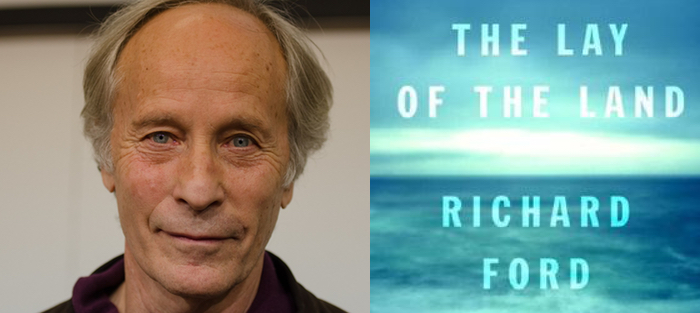

Hailed by Michiko Kakutani as “one of his generation’s most eloquent voices,” Richard Ford is the best-selling author of six novels and three short story collections, including Rock Springs and The Sportswriter, both widely considered modern classics. His novel, Independence Day, was the first book to win both the Pulitzer Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. A recipient of the Rea Award for the Short Story, his stories have been widely anthologized. His most recent novel, The Lay of the Land, was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award in 2006, and is the final book in the Frank Bascombe triology.

The interview that follows was conducted by e-mail in early 2011.

Interview:

Travis Holland: With The Sportswriter, you introduced readers to Frank Bascombe, a character you’ve continued to follow in two more critically acclaimed novels—Independence Day, and most recently, in 2006, The Lay of the Land. What was the genesis of Frank Bascombe? Can you speak perhaps to what inspired you to write about a writer who’s essentially walked away from writing—at least, writing fiction?

Richard Ford: Oh, the first genesis of Frank is probably like the genesis of most fictional characters—complicated. But then whatever “he” was in the first novel has to be re-genesis’d in the next. And so on. It’s not as if “he’s” waiting around intact, like Charley McCarthy, to take his next turn on stage. The “Frank” in one book differs from the “Frank” in the next – even though I might’ve felt he was, and wanted him to be, the same when I started to write about him again. But after all, his creator—me—is older each time I take him up again; my interests are different from the prior time I wrote about Frank (I’m giving up putting him in quotes now….you get the point); my purchase on writing sentences is different (and Frank is nothing if not just a bunch of sentences strung together). So first he had one genesis, then he had two more (although the subsequent two were certainly somewhat based on the prior). Have I made him confusing and pretentious enough now?

You probably just innocently mean, however, what was his genesis the first time I came to imagining him. Well, first I had a bunch of things I wanted to tell—that is, raw materials I wanted to put into a book I would try to write. I began casting around for some way a telling voice would sound, a voice that would let me get in all the diverse stuff I wanted to have in my prospective book—serious stuff about a child’s death, comic stuff about sportswriting, brainy stuff I’d supply along the way about both of these previous matters. And plenty more: writing about New Jersey, for instance, and about marriage. I’d read some novels that offered clues to how this complex and capacious facility might be achieved. I’d read Something Happened, by Joe Heller; I’d read “A Fan’s Notes,” by Frederick Exley; and I’d read The Moviegoer, by Walker Percy. In their own ways—in first person, mostly, with present tense verbs—these books did something I wanted to do. So I started writing sentences just in a provisional way—in notes—that used their basic strategies, and I played the strategies over the material I wanted to put in the prospective book. One thing led to another. It began to seem attractive that a character-narrator would be a sportswriter, and that in trying to tell (for instance) what a sportswriter did and why a person might like doing that as a job, the telling began to sound the way it did. I tried that sound out over the whole set of concerns I had stored up for the book-to-be and it seemed to have that necessary facility, suppleness, comic and serious capacities. Frank was just the accretion or the accumulation of a particular way of telling and what that telling sounded like.

You probably just innocently mean, however, what was his genesis the first time I came to imagining him. Well, first I had a bunch of things I wanted to tell—that is, raw materials I wanted to put into a book I would try to write. I began casting around for some way a telling voice would sound, a voice that would let me get in all the diverse stuff I wanted to have in my prospective book—serious stuff about a child’s death, comic stuff about sportswriting, brainy stuff I’d supply along the way about both of these previous matters. And plenty more: writing about New Jersey, for instance, and about marriage. I’d read some novels that offered clues to how this complex and capacious facility might be achieved. I’d read Something Happened, by Joe Heller; I’d read “A Fan’s Notes,” by Frederick Exley; and I’d read The Moviegoer, by Walker Percy. In their own ways—in first person, mostly, with present tense verbs—these books did something I wanted to do. So I started writing sentences just in a provisional way—in notes—that used their basic strategies, and I played the strategies over the material I wanted to put in the prospective book. One thing led to another. It began to seem attractive that a character-narrator would be a sportswriter, and that in trying to tell (for instance) what a sportswriter did and why a person might like doing that as a job, the telling began to sound the way it did. I tried that sound out over the whole set of concerns I had stored up for the book-to-be and it seemed to have that necessary facility, suppleness, comic and serious capacities. Frank was just the accretion or the accumulation of a particular way of telling and what that telling sounded like.

What’s it been like to write about Frank over the course of three novels? As readers, we’ve had the unique experience of accompanying him from his late thirties into his mid-fifties, with all that entails. And it entails so much, as any life does. What has that experience of deeply immersing yourself in the imagined life of a character been like for you as a writer?

I’ve liked that experience of immersion; I’ve felt friendly to the enterprise of making Frank up; I’ve (as little as I ever “believe” my characters are remotely human) liked and enjoyed his putative company—although his company is just me feeling cozy, amused, and challenged with writing him. I guess I think it’s what every writer wants and wants to do—fortuitously to come upon a big subject with agreeable formal terms that can consume an immense part of one’s life with a good outcome for the reader. When John Updike died, Adam Gopnik wrote in the New Yorker that John was a writer who “got it all in,” who rendered himself “fully expressed.” Writing this piece of artifice called Frank Bascombe has allowed me to do the same. It’s quite lucky, and quite satisfying.

Reading your novels—particularly the Frank Bascombe novels—one comes away with a remarkably vivid and complex portrait, not only of your characters but of middle class America. In terms of narrative time, the Bascombe novels cover only a relatively short span of days, and yet each book manages to pin down a particular moment in American culture. Such is the case in The Lay of the Land, which really nails down what it felt like to live in the United States in 2000—a liminal moment indeed, between the rather heady exuberance of the 1990s and what would turn out to be a decade of deep pessimism. Was it your intent to do this? Do you see this pining down of place and time as being in any way the responsibility (among the many responsibilities, perhaps) of a novelist?

It was my intent to do this. It was part and parcel of each novel’s big-ness: that each one take on some salient bits of our time and culture and politics, and render them vivid and vividly considered, and perhaps try to say something fresh. I don’t, however, think that doing what I did is anybody else’s novelistic responsibility. In writing novels a writer is utterly free to do, or not do, whatever she or he pleases.

What is the primary responsibility of a writer? Is it to oneself or the reader?

Oh, I don’t like questions like this. Or maybe I just don’t like the answers they usually elicit. When I was a young man my responsibility seemed to be to see if I could write a novel at all. I hadn’t any readers. Then when I got some readers (quite a while later), I began to think about what I could do to interest those readers and maybe bring in some more. Now, at age sixty-six, I think a lot about readers. I mean, I’m a reader. I know what it takes to interest and divert me. I have a very exalted working definition of what literature is. It’s Leavis’s dictum: that literature is the supreme means by which we renew our sensuous and emotional life and learn a new awareness. That’s literature from the reader’s point of view—as if the reader were the final destination and ultimate decider about what literature is. So I’m raising that readerly question with myself most of the time: am I satisfying Leavis’ injunction for a reader? Am I trying to do that? Am I failing to do that? And I know this: that if I didn’t have some readers now—if someone told me I didn’t have any—I’d goddamn hang it up. Umberto Eco says writing is an act of love. I don’t know if I’d quite go that far. But it’s sure an act that bespeaks respect for the reader who’s destined to read what I write.

So if literature is the means by which the reader renews his or her sensous and emotional life and learns a new awareness, and if, as so often seems the case these days, people are reading less, or at least reading less literature that seeks to live up to Leavis’s dictum (I’m thinking here about the fiction that tends to populate most best-seller lists, much of which seems to be attentive to the dictum of the empty calorie: fast and forgettable), what do you think that says about our times? Has there been a shift in what readers tend to seek out, in terms of literature? Does our current literary culture say anything about America in 2011?

This asks for a generality, a social scientist’s response. I don’t know. At this point I shift from concern for the reader to thinking what I can best give to a reader—using my little “value system.” I give a reader what I think a reader needs, and I’ve always thought the reader needs (and perhaps secretly wants) books that subscribe to Leavis’ injunction. Readers need that no matter what else they’re reading; so I go on trying to give it to them, unworried.

How do you go about your research? Particularly with novels like Independence Day and The Lay of the Land, where Frank Bascombe is neck-deep in the real estate business, I imagine you must have done a good deal of research. Is this an aspect of fiction writing—that is, the work that orbits around the writing in order for the writing to occur—that appeals to you?

Actually, I’m probably a novelist in part because I detest anything having to do with reporting. That is, research. I just lack the basic fact-finding instinct. So I found a way to be a writer that doesn’t require exhaustive research. For instance, I wrote a novel about real estate because I decided if I wanted to write a second novel with Frank Bascombe as its narrator, I had to change his job. I’d gotten, I felt, all I could out of sportswriting in the first novel. So, I cast around for what I already knew anything about and was also interested in, and that a person like Frank could “become” in mid-life without going back and doing a lot of training (read: that I’d have to do a lot of research for). I already knew—from life—a lot about real estate. So I made him be a real estate salesman. To completely muscle up for that writing I spent most of a year noting down and rigging around all I knew and could casually learn about real estate, including reading the New York Times, and making the rare but painful fact-finding call to the National Association of Realtors. And also I went on with my life’s preoccupation—which is looking at houses that are for sale, now and then renting a house in some far-flung place, talking to realtors. In other words, I just began to take seriously something I’d always done for pleasure—think about houses, architecture, selling houses, the economy.

Actually, I’m probably a novelist in part because I detest anything having to do with reporting. That is, research. I just lack the basic fact-finding instinct. So I found a way to be a writer that doesn’t require exhaustive research. For instance, I wrote a novel about real estate because I decided if I wanted to write a second novel with Frank Bascombe as its narrator, I had to change his job. I’d gotten, I felt, all I could out of sportswriting in the first novel. So, I cast around for what I already knew anything about and was also interested in, and that a person like Frank could “become” in mid-life without going back and doing a lot of training (read: that I’d have to do a lot of research for). I already knew—from life—a lot about real estate. So I made him be a real estate salesman. To completely muscle up for that writing I spent most of a year noting down and rigging around all I knew and could casually learn about real estate, including reading the New York Times, and making the rare but painful fact-finding call to the National Association of Realtors. And also I went on with my life’s preoccupation—which is looking at houses that are for sale, now and then renting a house in some far-flung place, talking to realtors. In other words, I just began to take seriously something I’d always done for pleasure—think about houses, architecture, selling houses, the economy.

In another instance, writing The Lay of the Land, I decided Paul Bascombe, Frank’s recalcitrant son, ought to be a greeting-card writer. And (but again, it was really just for fun) I called up the Hallmark people in Kansas City and persuaded them to let me spend some days hanging around their card-writing departments. This was wonderful in more ways than I can describe. I loved it. I sat in on writing meetings, I wrote my own cards, commented on others’ cards, all that and more. I found I had a kind of low-impact passion for it. And it was such a lucky instinct for me. I came away with a huge respect for the Hallmark writers, which then allowed me to write Paul into the book in a way that was full of sympathy, but was also fairly well informed. You have to get lucky in making these sort of decisions. I could never just do a lot of cold research and expect to have any emotional purchase on the material. The emotional purchase comes first.

I’m trying to picture you writing greeting cards, and imagining the greeting cards you might have created. Oh, I’d like to see those. What was it you liked so much about this particular experience?

I wrote (that is, I amateurishly participated in the writing meetings for) “Shoebox” cards—a line of Hallmark cards that are witty and wry and clever. Someone just gave me one for my 67th birthday, in fact. I liked being in on the writing and analyzing and discussing of these cards because the people in the meeting were immensely smart and witty themselves, and the cards gave vent to a genuine sense of humor—not the factitious, cloying, un-humorous humor of most greeting cards. And I liked that because even though the cards weren’t striving really for much more than wittiness (pun-ish plays on words, switcheroos, deft absurdities), they weren’t the least cynical, and they seemed to give vent to the writers’ real sense of what was funny. I like that sense that the cards allowed their writers to be fully-expressed, and that their work gave them rich satisfaction. The ones I semi-wrote, it should be said, were distinctly inferior.

As an author, you’re known for having moved around quite a bit while still being able to get your writing done. You’ve written stories on airplanes, in hotels; you’ve produced fiction here in the States and abroad. Was this way of working—whenever and wherever the opportunity arose—one you consciously and deliberately cultivated, or have you always been able to write like this?

I’m just practical. Life comes first for me; art second. Sometimes art comes even later than second. If I was going to live the way I wanted to (going hither and yon), it was going to be necessary that I be flexible about where I write. These mandarin-precious-princess-and-the-pea notions about a writer’s “special place” just didn’t match my life. Which isn’t to say I don’t normally have a room where I write in the house where I live, and that I don’t like that room to be quiet, with no distractions. I do. But that isn’t always the opportunity life affords. There used to be a writer, whose name I won’t mention, [Raymond] Carver and I used to laugh about. He’d take journalists into his inner sanctum of a writing room and say, “This is where I make the magic.” Well, I make the magic wherever I can. I don’t know if that’s conscious or accidental.

How have your stories and novels been influenced by the places in which they were written?

Not uniformly. I grew up in Mississippi and Arkansas, and arrived at the idea of writing a novel crippled with the unquestioned assumption that I was supposed to write either about those places, or about people who lived there. Or else I was supposed to set my novel there, which I did. Or that I was supposed to write for a southern audience. Anyway, I did it. And eventually, along with other dissatisfactions, I concluded I didn’t have anything new or fresh to say by following those suppositions. I needed therefore to set my books elsewhere, where I might be able to bring some news, and to write for a much wider audience than just southerners—which I’ve done.

Another way of thinking about this is that I wrote about suburban New Jersey and set the Bascombe books there because—at the beginning—I was living there and it seemed available and rather un-worked-over by other writers. I wrote about Montana—or set stories and novels there—because I’d been there and was persuaded I could appropriate things about that place to make the stories I was writing more persuasive. I also set two novellas in Paris because I loved Paris and thought that Americans writers were free to set stories there.

I would only say, however, that once I left off writing stories set in the South, I never felt that the places where I set my novels were at all genitive. I was never seeking to the “find the essence” of a place. I don’t think places have essences any more than people do. The places as they contributed language to the stories, and settings, were always (in my mind) subordinate to what the characters were doing. They were background—even, as in the Bascombe books, New Jersey becomes a subject of Frank’s musings. When in Independence Day, Frank says, “place means nothing,” I was (and he was) trying to say something along the lines of Auden’s famous, and famously misused, remark about poetry. It’s not that it’s not important. It is important. But its importance is subtle and probably less pronounced and maybe less weighty than one might imagine.

Bottom line: place never made any story happen—not the ones I write.

Can you talk about some of the books and writers who continue to serve as touchstones for you. The writers, books, or stories, you find yourself rereading, revisiting, or simply like to have around as you do your own work.

I’m a disorderly reader. Books come randomly into my life, exert themselves on me, then pass on. Last year I read Vasily Grossmann’s cables from the eastern front, and immediately wanted to appropriate individual lines from it (it’s translated, of course) as titles to a book of stories I was writing. Now I wonder why I wanted to do that. Most of the “greats” from my young writer-hood I never revisit: Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Bellow, Babel, Dostoievski. Welty’s an exception. I read her still. Cheever, too. I’m a slow reader; and going back to books prevents me from going forward to new books. And then books come along that would seem to have nothing to do with anything I might write—like Blake Morrison’s And When Did You Last See Your Father?. I deeply admire it and have it by my table while I’m writing this book set in Canada. Touchstone books….I don’t know. So Long, See You Tomorrow; The Moviegoer; A Fan’s Notes; Alice Munro’s stories. These still resonate audibly.

You mentioned Eudora Welty. You were friends, yes? I wonder, what is it about her work that continues to resonate with you? (I ask this, having only recently reread her story “No Place for You, My Love,” which just knocked me out.)

Well, “No Place For You, My Love,” is one of the greatest short stories of the century, unquestionably. But it isn’t especially typical of Eudora’s work, either. Although when I say that I start thinking of other atypical stories of hers, and it makes me think there isn’t a typical Welty story. What I like, what endures for me, is the rich mixture of humor in all of her work. She’s very, very funny—her writerly eye seizes on such a wealth of detail that often makes its way into her sentences as subtle humor; but she’s also being funny often at the service of being very serious. Flannery O’Connor (also a great story writer) was both funny and serious at once. But O’Connor was so scathing about experience and life. You leave her stories always shaken. Whereas Eudora is tolerant, her intelligence supple, her sympathies wide and widening, her personal pleasure (glee, often) at being a source of readerly pleasure so palpable. I sometimes say that growing up in Mississippi one learned that human discourse—conversation, say—was largely about keeping your fellow conversationalist amused. Spending time with Eudora was always to be amused. Nothing was lost on her. Language was always in play. Drama—tiny and large—was popping up everywhere. Her stories are just the same. Even in this New Orleans story [“No Place For You, My Love”]—a very steamy story about an almost-romance—there’s humor everywhere you look. And the effect is to enrich the steaminess.

Well, “No Place For You, My Love,” is one of the greatest short stories of the century, unquestionably. But it isn’t especially typical of Eudora’s work, either. Although when I say that I start thinking of other atypical stories of hers, and it makes me think there isn’t a typical Welty story. What I like, what endures for me, is the rich mixture of humor in all of her work. She’s very, very funny—her writerly eye seizes on such a wealth of detail that often makes its way into her sentences as subtle humor; but she’s also being funny often at the service of being very serious. Flannery O’Connor (also a great story writer) was both funny and serious at once. But O’Connor was so scathing about experience and life. You leave her stories always shaken. Whereas Eudora is tolerant, her intelligence supple, her sympathies wide and widening, her personal pleasure (glee, often) at being a source of readerly pleasure so palpable. I sometimes say that growing up in Mississippi one learned that human discourse—conversation, say—was largely about keeping your fellow conversationalist amused. Spending time with Eudora was always to be amused. Nothing was lost on her. Language was always in play. Drama—tiny and large—was popping up everywhere. Her stories are just the same. Even in this New Orleans story [“No Place For You, My Love”]—a very steamy story about an almost-romance—there’s humor everywhere you look. And the effect is to enrich the steaminess.

I’m thinking again about Leavis’ dictum, how, as you said earlier, literature is the supreme means by which we renew our sensuous and emotional life and learn a new awareness. And it seems to me that short stories, when done well, are a near perfect representation of this ideal in action. Certainly your stories (from Rock Springs, Women with Men, and, most recently, A Multitude of Sins) have had this very impact on a great many readers, including myself. What is it about the short story as a form that continues to engage you as a writer and a reader?

You know, I’ve made a lot of valiant and failed attempts as an anthologizer/editor to come up with an idea about what makes a short story such a winning form. Again, generalities may not be my best rhetorical mode. Being a fiction writer, I’m kind of wedded to the particular, not the general. “The hard brown nut-like word,” as Barthleme writes in “Indian Uprising,” is where I position my pennant. I mean a bad short story is not engaging at all. The form doesn’t preserve it. I’m not sure the form means much—especially since it’s practiced in all kinds of ways, with all possible assaults on verisimilitude, at many lengths, with endless effects. Basically a well-written short story—were you to excerpt one paragraph—wouldn’t read any different from a well-written novel. The level of verbal felicity seems about the same, genre to genre. So, I guess I have to say—and I’ve said it before—it’s the length. And nothing especially exotic about the length. A short story—if it’s good—gives you very good writing, and you don’t have to commit your life (or your week or your month) to reading the whole thing. It’s a lesser form for this reason. It has lessavoir du poids. My dear Carver can be heard now objecting from his place of rest. I used to taunt him about the short story being a lesser form. And of course in his hands it almost wasn’t. But it is. No offense intended.

Yet you’re certainly a champion of the short story. In fact, a new anthology you just edited called Blue Collar, White Collar, No Collar: Stories of Work, is coming out in just a few days, the proceeds of which benefit 826michigan. Can you talk about why this project was so important to you?

It’s important to me for several reasons, the chiefest of which is to be able to assist 826michigan in its noble mission to serve the youth of southeastern Michigan by teaching kids to write, giving them confidence to do better in school, helping them with their homework after school hours, and addressing many other really critical needs of kids trying to succeed in a demanding world. 826michigan performs these services free to the kids. So the proceeds of the sale of this anthology all go to that good end. Beyond that, editing an anthology gives me a chance to find a few new readers for my colleagues’ excellent work. And the premise of the book – stories about work – seemed apposite to all that Michigan means to your average American: a place where work matters. And, of course, doing the book allowed me to renew my long-standing affiliation with the state, which has meant so much to me in my life and given me so much.

It’s important to me for several reasons, the chiefest of which is to be able to assist 826michigan in its noble mission to serve the youth of southeastern Michigan by teaching kids to write, giving them confidence to do better in school, helping them with their homework after school hours, and addressing many other really critical needs of kids trying to succeed in a demanding world. 826michigan performs these services free to the kids. So the proceeds of the sale of this anthology all go to that good end. Beyond that, editing an anthology gives me a chance to find a few new readers for my colleagues’ excellent work. And the premise of the book – stories about work – seemed apposite to all that Michigan means to your average American: a place where work matters. And, of course, doing the book allowed me to renew my long-standing affiliation with the state, which has meant so much to me in my life and given me so much.

Finally, how do you hope these stories might appeal to readers?

I don’t think the premise of the book overshadows the stories themselves. I’ve identified the stories as having to do with work, and insofar as the premise is a fair one – and I believe it is – the stories will turn the diamond of work this way and that and show work’s various facets to advantage: principally its consequence in peoples’ lives, its centrality as a legitimate subject of contemplation, its simple interest to us as a force in our lives. But in saying that, I’m just pointing out what excellent fiction routinely does to any subject it seizes: it shows us where importance lies when we might’ve thought we knew better; it elevates in importance a human concern or pursuit that might’ve been taken for granted; it pleases and informs us about subjects of genuine moral interest. To me, these are gifts of literature which have rather enduring appeal.