Tatjana Soli’s The Lotus Eaters is a stunning debut novel set in the Vietnam War. Helen Adams drops out of college and makes her way to Saigon, hoping to witness history in the making. She learns the trade of combat photography from Sam Darrow, a veteran journalist who becomes her lover. Helen conquers her fears, survives battle, and masters the art of distilling a relentless human tragedy down into single images. Like many of the soldiers she documents, Helen is sent home wounded, only to find that there’s no longer any place for her stateside. Back in Vietnam for a second time, Helen falls in love with Linh: a mysterious cross between photojournalist, soldier, and spy—a man caught between the foreign and domestic forces tearing his country apart.

Tatjana Soli’s The Lotus Eaters is a stunning debut novel set in the Vietnam War. Helen Adams drops out of college and makes her way to Saigon, hoping to witness history in the making. She learns the trade of combat photography from Sam Darrow, a veteran journalist who becomes her lover. Helen conquers her fears, survives battle, and masters the art of distilling a relentless human tragedy down into single images. Like many of the soldiers she documents, Helen is sent home wounded, only to find that there’s no longer any place for her stateside. Back in Vietnam for a second time, Helen falls in love with Linh: a mysterious cross between photojournalist, soldier, and spy—a man caught between the foreign and domestic forces tearing his country apart.

Soli has created an epic war novel, with an ambitious scope that spans years, characters, and countries. Her book belongs in the upper eschelon of the Vietnam canon. Here, Vietnam is more than a war. We see urbanites and expats in Saigon, farmers and fishermen in small villages, the Killing Fields of Cambodia, journalists with a range of motives, as well as protesters and grieving parents in the States.

With a strong woman behind the lens and under fire, Soli bridges the gap between the soldiers in the field and the observers around the dining room table. The book is at once a tremendous document of a historical era and a timeless story of love and aspiration. The Lotus Eaters isn’t just about how we fight wars; it’s about how we live with them, how we watch them, and how we turn them into history.

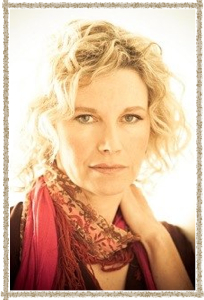

From the author’s website: Tatjana Soli is a novelist and short story writer. Born in Salzburg, Austria, she attended Stanford University and the Warren Wilson MFA Program. Her stories have appeared in The Sun, StoryQuarterly, Gulf Coast, Other Voices, Third Coast, Carolina Quarterly, and North Dakota Quarterly among other publications. Her work has been twice listed in the 100 Distinguished Stories in Best American Short Stories and nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She was awarded the Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Prize, the Dana Award, finalist for the Bellwether Prize, and received scholarships to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. She lives with her husband in Orange County, California, and teaches at the Gotham Writers’ Workshop.

From the author’s website: Tatjana Soli is a novelist and short story writer. Born in Salzburg, Austria, she attended Stanford University and the Warren Wilson MFA Program. Her stories have appeared in The Sun, StoryQuarterly, Gulf Coast, Other Voices, Third Coast, Carolina Quarterly, and North Dakota Quarterly among other publications. Her work has been twice listed in the 100 Distinguished Stories in Best American Short Stories and nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She was awarded the Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Prize, the Dana Award, finalist for the Bellwether Prize, and received scholarships to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. She lives with her husband in Orange County, California, and teaches at the Gotham Writers’ Workshop.

Interview:

At the risk of sounding obvious: Why Vietnam? What is it about that war that captured your imagination?

My mother worked as an interpreter for NATO in Italy in the late sixties. From there, we moved to Fort Ord in Monterey, CA. As a young girl, living on a military base, I was surrounded by this frightening thing that was happening. My friends’ fathers would be shipped off, and there would be tears. Sometimes a car would pull up to a house, and I remember the dread on all the faces around me. A few days later the family would disappear. So the war in its mysteriousness haunted me from an early age, and when I grew up, I read every account I could, trying to come to some conclusion about what happened.

Why do you think that episode in our history continues to fascinate us and demand reinterpretation?

Well, there are still plenty of novels being written about WWII. But Vietnam is unique in that it made people distrust their own government, totally reject the establishment. People became cynical and disillusioned by the lies they were fed about the necessity of the war, about the sacrifices being made, but there was also this great power in knowing the truth, in agitating for change. The access photojournalists had in that war was one of the reasons the truth came out. That freedom, by the way, no longer exists. I see many parallels to the situation today in Iraq and Afghanistan, but there is an apathy on the part of the public compared to the 60’s and 70’s.

As far as reinterpretation, the seminal works about Vietnam for me are Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried and Going After Cacciato, Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers, and Michael Herr’s Dispatches. All focus on the disconnect between the official line our government gave us and the reality those on the ground faced. Those writers moved past the obvious “war is hell” theme. For me, the reinterpretation came with introducing the particularities of place into the war. War doesn’t occur in a vacuum, it occurs in someone’s birthplace, it destroys their home, their family.

I’m really glad you mentioned the “lies about the necessity of war.” One of the things that I find most interesting about The Lotus Eaters is Helen’s agency—the fact that she chooses to go and to stay and to go again. So much of our mythology of Vietnam (and other wars) is wrapped up in the draft—young Americans who have no choice. In your novel, many of the characters are opportunists who choose go there to advance their careers. In fact, the only characters that truly have no choice in the matter are the Vietnamese. Were you trying to show that a sort of adventure/glory-seeking is a part of war? That there is always a choice, on somebody’s part?

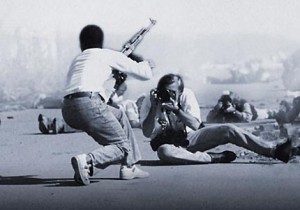

War photographer James Natchwey

Journalists are a special case, and one of the reasons that writing the book fascinated me. They go of their own volition; they put their life on the line on a daily basis. And the reasons are as complex and varied as the individuals. The biggest reason I came across, again and again, both in Vietnam and in more recent conflicts, is this desire to be there to record history in the making. The adventure/glory of getting the image, the story, that comes to define an event. It’s almost become a truism that without the recording of an event, it disappears. Margaret Moth said that in her opinion it was the best job in the world. But there is a price to be paid: the danger physically, the burnout mentally. You have to make that part of your choice. And if you go back knowing the risks, is that addiction to danger, or acknowledging that the risk is worth the greater good of knowledge? I’m immensely grateful to the men and women who take these risks, who bring us back these stories that perhaps wouldn’t get told otherwise.

Could you talk about your research process for this novel? It feels incredibly well-informed. Was there a historical Helen Adams? Were any other characters based on real people?

In retrospect, I would say that ignorance is bliss. Not only did I have to figure out how to write my first novel, but then I had to write about a time and culture that required extensive research, and then because this is well-known territory, I had to be accurate for people who had actually experienced the war, but still make it my own.

Dickey Chapelle

I spent almost a year gathering facts, tidbits, ideas, pictures, music. I filled notebooks and notebooks, wrote a first draft that was fairly dry. And then I kind of let it all go, allowed myself to remember the research that stuck with me, forget the rest, so that it became more organic to the story. I went back to telling a story, creating characters, and that changed much of the plot, did away with lots of hard-won research. Painful, but necessary. Research has to be in service of the story, and not vice-versa.

Catherine Leroy

There were a handful of female photojournalists in Vietnam. The ones that particularly intrigued me were Dickey Chapelle and Catherine Leroy. But I took my character farther in terms of being consumed by the war, consumed by the country, the complexities of combat photojournalism. There was a real Vietnamese spy, Pham Xuan An, who worked undercover for Time magazine that I used for part of the story of Linh. But these “facts” are peripheral to the main thrust of the story.

I have received many letters from people who served in Vietnam, both in civilian capacity and military, who said that the book brought the time back to them. I’m incredibly proud of those letters. But I’ve also received letters from people who had fathers, uncles, husbands, etc. who served, and they said that the book helped them understand what those loved ones went through.

Did you travel to Vietnam (and/or Cambodia) in the course of writing this book?

I traveled in Asia briefly with my husband years before I thought of writing the book. Once I was deep into the research, I planned a trip to Vietnam that had to be cancelled due to a family emergency. But then a strange thing happened once I had the first draft down—I had this particular place so strong in my head, it was literally feeding the story. I was afraid that if I went to Vietnam that the difference between what was in my imagination and what I found in contemporary Vietnam would break the dream of the story for me. Going back to your research question, I found the right detail set off a chain of events; that was its value rather than strictly providing verisimilitude for the book. I liken it to the movie Apocalypse Now. That is a fever dream of Vietnam, Coppola’s dream of Vietnam. You aren’t going to find that place on a tour. The Saigon of the book is one made from my characters: Helen, Linh, and Darrow. I’m happy beyond belief when I have people tell me that they were there, and the book brings the time back to them, but the setting is foremost an organic thing intertwined with the characters. I’m planning on finally taking the trip this winter. I think it will be an amazing experience.

providing verisimilitude for the book. I liken it to the movie Apocalypse Now. That is a fever dream of Vietnam, Coppola’s dream of Vietnam. You aren’t going to find that place on a tour. The Saigon of the book is one made from my characters: Helen, Linh, and Darrow. I’m happy beyond belief when I have people tell me that they were there, and the book brings the time back to them, but the setting is foremost an organic thing intertwined with the characters. I’m planning on finally taking the trip this winter. I think it will be an amazing experience.

This must’ve been a very daunting project to undertake. Did you find it intimidating to write about a subject that (a) had been tackled by so many literary heavyweights, and that (b) many of your readers might have experienced firsthand?

I did find it intimidating. But I really believe that if the story is important to you as a writer, you will find a way to make it your own. I don’t think you can cynically choose a subject because it is topical and hope to pull it off. It has to come from inside, be a passion. Actually, I had the opposite problem with Vietnam. Both agents and editors told me it was a small, niche market, dominated exclusively by military books for a male audience. But that was precisely the reason I thought there was room for a bigger, more inclusive story, that I could tell.

I think readers who actually were there firsthand accept the book because of whatever story truth I was able to convey, which is different than fact truth. Although I tried to be faithful to the general facts, this is not a non-fiction book. The primary focus here is on the effect of the war on characters, who are entirely fictional.

Speaking of characters, I was hoping we could talk a little about Linh—who I found to be remarkable. I guess what fascinates me is how much he defies any sort of easy categorization—in terms of his role, his allegiances, etc. What was the origin of this character? What can he tell us about the Vietnam War and other, subsequent conflicts?

Linh was really central to why I wanted to write the book. It seemed obvious that in a war that dragged on for over a decade, there would be much contact between the cultures, especially off-duty in Saigon, and yet I found very few accounts of a Vietnamese point-of-view. Linh by no means stands for every Vietnamese, in fact his situation is so complex he ends up a very isolated character, and yet he is the heart of the book. Before and during the novel, I had written a lot of short stories about Vietnamese immigrants in California, and he was the natural starting point for that story. In the early drafts, it was simply about his trying to survive the war, but in the way of a novelist complicating the lives of her characters, one day Mr. Bao showed up. People, including his own, assign Linh roles that have nothing to do with who he is inside. Historically, there was a famous Vietnamese spy, Pham Xuan An, who worked as a reporter for Time, and who the Americans were shocked to learn was a spy after the war was over, but Linh’s situation is both less sensational and more complicated than that one.

The one common thread in most accounts of vets returning to Vietnam is how accepting the Vietnamese people are. There is very little hostility over the war. And the vets often find healing by exchanging stories with their military counterparts, realizing that under all the slurs, the stereotyping, these people are essentially the same as they are. What was amazing about the access that journalists had in Vietnam is how it did at least show us to some extent the civilian toll. From what I’ve been able to read from various journalists in today’s wars, that freedom no longer exists in the same way. I worry that we are not getting the equivalent of Linh’s story in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Could you tell me about the title of The Lotus Eaters? That’s from Homer, is it not?

The title does come from The Odyssey:

Those who ate the honeyed fruit of the plant lost any wish to come back and bring us news. All they now wanted was to stay where they were with the Lotus-eaters, to browse on the lotus, and to forget all thoughts of return.

For me it was a metaphor for what the war does to all the characters. They literally lose themselves inside of it. You go to war with all these plans and goals, and you end up not caring about any of it. Just like the soldiers, many of the journalists could not imagine going back to “normal” life. It’s much more complicated than a simple addiction to danger, an addiction to the adrenaline of war. For Helen in particular, it’s a stripping away of naïveté, of innocence. How can you go home when you’ve become a different person? When you no longer fit?

To take things in a bit of a craft direction, I wanted to go back to what you said earlier about the emphasis on character as opposed to fact. What would you say is the novel’s role, in a world where narrative nonfiction—and unreliable journalism—are so prevalent? Do you have any advice for writers who struggle to incorporate history (or current events) into their work?

I don’t mean to mislead — I absolutely think that the burden is on the writer to be as historically correct as possible. But that is just the baseline, the beginning, if you will. Then storytelling goes on top of that, and the storytelling has to be just as compelling and character-driven as a fiction that didn’t require research. No one wants to read your research—they are looking for story. That’s why they are reading a novel, to be immersed in time and place and character. The temptation as a writer is to include these inert sections of facts simply because you’ve gathered them. Just guessing, I’d say I used less than five percent of the material that I had available to me. Inefficient, yes, but also necessary for my process. You don’t know what you are looking for until you find it.

Speaking of research, your descriptions of photography are very well-informed and convincing. Was this another area of research for you? Have you worked as a photojournalist or photographer?

I did do research on basic photography, and, especially, tried to convey the hardships these photographers worked under. Film got destroyed all the time – whether under the conditions out in the field, or back in the less than optimal darkrooms. Often film was sent out on planes to avoid censorship. Sometimes it wouldn’t make it through. So the medium almost became a metaphor itself. And what is really fascinating is that this is all historical research now. With digital photography, a picture can be sent around the world in seconds. An amazing change. Although apparently the desert conditions of Iraq and Afghanistan wreak havoc with computer equipment.

You mentioned that you wrote several short stories about Vietnam before writing The Lotus Eaters. Do you feel a sense of closure on this subject? Will you write about Vietnam again?

That’s funny that you ask that because until recently I would have answered that I had finished with the war. But a new non-fiction book came out that I had missed, and I started reading it and immediately I plunged back into that time. It felt like home.

I wrote many stories about the Vietnamese immigrants as I gathered my research for the war. I had so many ideas that the original book started splitting in two different directions, which my editor wisely convinced me to delete. But I still have those hundred pages in my files. I would love to develop that story some day. Right now I’m finishing up my second novel set in contemporary California, but at some point in the future I’ll definitely go back to Vietnam.

Can you tell me a bit about the new novel?

Well, I had bitten off so much with the first book, so intense in research in so many different areas, that I wanted a completely different challenge as a writer this time. I’m superstitious about saying too much, but it is set on an isolated citrus ranch in Southern California. Although it is an entirely different kind of book, I think some of the same themes are there: issues of race, dislocation, healing. It’s providing the right kind of stretch for me as a writer in terms of content and craft. I’m very engaged with the story, which I kind of doubted after the obsession of writing the first book. The great gift of writing a second novel is that even when things feel hopeless, you know you’ve gotten through it one time before.

Do you have any advice for aspiring fiction writers and novelists?

Well, I’m not the most practical writer so I’m not sure how useful my advice is. But I think most writers are idealistic, otherwise why be in such a problematic business? I really wrote the book I wanted to write, regardless of its marketability. It was a hard sell, but I was lucky to have a great team at St. Martin’s who really advocated for the book. So I’d say risk it, write what’s in your heart. Write with the big picture in mind. I’m proud that this was my first book AND my first published book. The realities of the marketplace, of the publishing world, are so complicated that there is no controlling that part of the equation. But you the writer can write the best book you are capable of. That’s the only thing in your control.

I definitely understand the temptation to chase trends, to write something with an eye to an audience, but ultimately, I don’t think that it will fulfill you over a whole career. A short story writer who I interviewed for an article on the writer career track works as a doctor, and his belief is that you’ve got to have a career that financially sustains you other than writing. If you give up that dream, you are free to write what you want and not worry about your bank account. He also makes the point that having a life away from the computer is a good thing. By necessity, most of us have that, but I think rather than resent these intrusions into our writing time, which I know I did, look at that time as making you the kind of person who has something to say when you get to the keyboard.

- Tatjana Soli will appear at the Carmel Public Library on Saturday September 7, and as part of “Between the Pages” at Town Hall in Seattle on September 16. For full details of those events and 7 more appearances on the West Coast visit her website.

- Read Soli’s essay for Three Guys One Book, titled “Loneliness, Love and Hemingway,” about the influence of The Sun Also Rises on her as a reader and writer.

- Listen to Soli discuss The Lotus Eaters and some of the history behind it, including archival footage of the Vietnam War, in this video: