Russell Banks / photo credit Larry D. Moore

Back in the fall of 2012 I had the opportunity to host Russell Banks as Visiting Writer for Warren Wilson College’s Harwood-Cole Lecture Series. Knowing he’d be in town for a few days, I arranged to interview Russell on my good pal Jeff Davis’ radio show Word Play. Forty years before, Jeff had worked on the literary magazine Lillabulero in Chapel Hill, which Banks co-edited with my father, the poet William Matthews. I’ve been reading Banks and turning to him as a mentor all my adult life. In many ways, the interview felt like a homecoming.

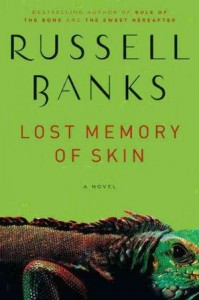

Banks’ new novel, Lost Memory of Skin, had recently come out in paperback. I’d just read it as part of a large project to revisit Banks’ extensive oeuvre. The night before, Russ had read from the new book, and we stayed up late afterward talking about life and literature with my good friend Keith Flynn. Banks and I met the next morning to record the interview.

Russell Banks is the author of more than a dozen novels, four collections of stories and two nonfiction works. Included among the numerous honors and awards Banks has received are the Ingram Merrill Award, the John Dos Passos Award, the Literature Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Continental Drift and Cloudsplitter were Pulitzer Prize finalists; Affliction, Cloudsplitter, and Lost Memory of Skin were PEN/Faulkner Finalists. Lost Memory of Skin was a Finalist for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. Banks was New York State Author (2004–2008) and is the founder and President of Cities of Refuge North America. He is the winner of the 2011 Common Wealth Award for Literature.

Interview:

Sebastian Matthews: The main character of your latest novel, Lost Memory of Skin, is called the Kid. Where did you find him? And could you talk a little about him as a character?

Russell Banks: Actually, he arose, as often is the case, out of a situation that I was aware of. The situation preceded the character, or the context preceded the character, or the house preceded the residence in a sense. I live six months a year, as you know, in Miami Beach in a condo with a terrace that looks out across Biscayne Bay toward the city of Miami to a causeway that crosses from the Miami Beach barrier islands over to the mainland. It’s called the Tuttle Causeway. And about four years ago I began hearing, then reading in the local newspaper, accounts of a colony of homeless men living underneath this causeway; and they were all convicted sex offenders who had served their time. Some of them were serious pedophiles or sociopaths. Some of them were just guilty of a sex crime such as indecent exposure for public urination, or some twenty-year-old kid having sex with his sixteen-year-old high school girlfriend, which is statuary rape. That’s a sex crime. But they were all lumped together because of a regulation that exists in the state of Florida whereby if you’re convicted of a sex crime, after having served your time, you can no longer live within 2,500 feet of any place where children live. So they were clustered together underneath this causeway with the encouragement, really, and connivance of law authorities and just dropped off there.

I could see this causeway from the terrace of my apartment. And I started to imagine some kid, some stupid kid…not necessarily “stupid,” but ignorant and naïve, a sexually-confused kid getting caught up by losing track of that line between fantasy and reality—maybe through pornography addiction or some kind of internet connection—and ending up committing what we call a sex crime and ending up living down there. Some kind of loser kid that just sort of falls through all the cracks of society…of which there is a super-abundance…and ends up down there, like a troll under the bridge. So the situation gave rise to my speculating about how a kid—say, my dumb nephew’s cousin, someone in my family, got down there. I can imagine, you know, some of the kids in my family ending up down there: kids who barely got out of high school, sub-literate in a sense, unemployable, but hooked on pornography or something.

So that was where the Kid came from. And within a page or two of trying to set down the Kid, to get inside the Kid’s head, he came alive for me in a way that I am gratified by and hopeful will happen every time I sit down to start writing a book. You hope that the character is going to come alive and the voice is going to get real in your ears.

Did you end up doing research on that community of men, or go down and check it out?

Did you end up doing research on that community of men, or go down and check it out?

I went down there and checked the place out in person and spoke with some of the residents. But I wasn’t interviewing them the way a journalist would. I just wanted to know what it smelled like, sounded like, looked like. I was there for sense impressions, which is what one builds a novel from. I already had my main characters by then, the Kid, the Professor, the Shyster, and so on. And I’d already done the legal research, the psychological, sexual, digital research.

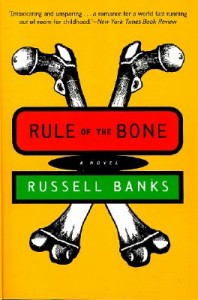

I want to ask you more about Lost Memory of Skin, but I’d first like to take a detour through Rule of the Bone. When Bone came out in 1995 comparisons were made to Huck Finn and Catcher in the Rye, which makes obvious sense—the braggadocio, the precociousness, the biting anger. Do you see a connection between Huck and Bone?

There are many of them. A drug addled boy…homeless…hanging around with an older Black man…[Laughs] Some of the connections there are pretty clear. I wasn’t trying to hide them…

Do you feel an affinity or a connection back from the Kid in Lost Memory of Skin to Bone? I am interested in specifically about the writing of both books—about their syntax and narrative stances. Because they are a little different…

Oh yeah, very different. The point of view is very different.

First person…

And then close third.

Very close third. Almost angelic, “in the head of.” Do you feel like they are related…

Oh they’re related, sure, but they are also quite different. Bone is a mid-90s kid and he’s also adolescent, he’s fourteen years old; and the Kid in Lost Memory of Skin is twenty-two years old. But still, he’s not an adult. He’s caught somewhere in that netherworld between childhood and adulthood…like so many males in America who are legally adults. So there’s a connection, sure, and he’s homeless the way Bone is homeless, and we’re dealing with some of the same themes. Sexual abuse of children in some ways. Bone is a victim of sexual abuse. And the Kid is accused of sex abuse. So there’s clearly a mirroring back and forth, and there’s linkage between the books. There’s a kind of dialogue, I suppose, going on under the radar in a way, going on between the two.

But they are very different kind of characters: the Kid is not anywhere near as worldly as Bone…he’s more alienated, let me put it that way, much more alienated…and disempowered. And he doesn’t have a narrative; he doesn’t have a story…in the way that Bone can begin that novel as he does, the same way that Huck Finn begins his story by jumping right into it… Bone’s got a set of links between the episodes of his life: he knows he went from point A to point B to point C to point D. So he can anticipate his future and in some ways existentially can create it. He’s much more in charge of his own destiny than the Kid in Lost Memory, who can’t tell his own story. He’s disassociated in a way. All he can talk about, his only connection is, his iguana Iggy… [Pause]

But they are very different kind of characters: the Kid is not anywhere near as worldly as Bone…he’s more alienated, let me put it that way, much more alienated…and disempowered. And he doesn’t have a narrative; he doesn’t have a story…in the way that Bone can begin that novel as he does, the same way that Huck Finn begins his story by jumping right into it… Bone’s got a set of links between the episodes of his life: he knows he went from point A to point B to point C to point D. So he can anticipate his future and in some ways existentially can create it. He’s much more in charge of his own destiny than the Kid in Lost Memory, who can’t tell his own story. He’s disassociated in a way. All he can talk about, his only connection is, his iguana Iggy… [Pause]

Did you know that Iggy Pop’s first band was called The Iguanas and that’s why he ended up with the name Iggy. [Laughs] I didn’t know that when I wrote that novel. I found out afterwards. An Iggy Pop fan wrote me and told me…

So, yeah, there are similarities, but there are big differences. Bone clearly has got a ghost text lurking behind it in the form of Huckleberry Finn, and there are allusions that are conscious and deliberate, and it is a kind of dialectical conversation going on between Huck Finn and Bone that I was aware of. The ghost text in Lost Memory of Skin is a different book, and about a third of the way through it I began to sense I was writing a story here about a boy who is not a boy, but is not a man either. He’s somewhere in-between: he’s innocent but not quite innocent, and he’s dealing with and hanging out with a larger than life man who is physically kind of grotesque—morbidly obese in this case—who seems to be custodial, but he’s also got his own agenda and isn’t quite trustworthy…and we’re talking about buried treasure here and we’re talking about the tropics and boats at sea…and pirates…and so I’m being reminded of something I remember from my childhood…and of course it was Treasure Island. Jim Hawkins and Long John Silver.

When I went back and reread it, I thought, Whoa, this is so much better than I remembered it. It’s not just a boy’s book; it’s really a kind of archetypal story. And why try to reinvent the wheel, I’ve got this model here and I’ll just start structuring it more or less as Stevenson unfolded his story and deal with some of the same ambiguities and complexities of relationship and so on…

That’s amazing. I was reading Treasure Island to my boy as I was reading your book…and I remember wondering about all the pirate maps…but I didn’t make that connection…

You didn’t make it? That’s good, that’s good that you didn’t in a way. It still operates on you, the archetypal structure.

Is it true that Rule of the Bone was written in a break in the middle of writing Cloudsplitter?

That’s right.

So I imagine finding the voice of Bone was in some ways really a treat…to take a break from that big historical narrative…

It was a great relief…[Laughs]

So much of the energy of Bone comes from the first person ramble…And I guess that’s what I am curious about. Did you find that the rhythm of the writing that you achieved with Bone is in any way similar to that of the Kid’s rhythm?

I ask because in some ways the angelic over-the-shoulder you use in Lost Memory at times makes it seem that the Kid is talking about himself in the third person. I know it’s more than that…He isn’t really talking for himself. And because these two books sound different than most of your other books, syntactically. Rule of the Bone is radically different than Cloudsplitter, for instance. And I realized that there’s a dearth of commas in Bone and in Lost Memory…they both run on in a talky way…

That’s right…That’s an intimate voice that Lost Memory uses. There is that close third where you get up into the head of the character but you don’t rely on the character’s first person narrative to tell the story. You use the diction that the character would be familiar with and comfortable with; and to some degree also the intonation and inflection and the syntax that the character would use. But you don’t look out through the character’s eyes in the same way. It’s a fabulous kind of point of view. It empowers the author in a way that allows you to both inhabit the character and also stand outside of the character at the same time. And I liked it very much, because I couldn’t really use the first person with the Kid…

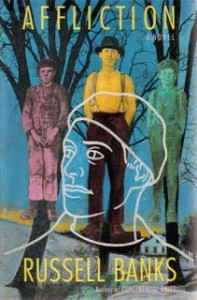

Another difference between him and Bone. Because the kid was so inarticulate to begin with and too out of touch with his own narrative in a way, and it would have made a very different kind of read and might have felt really claustrophobic. I ran into that in other texts where I realized that the character couldn’t tell his own story. So how can I tell his story without it sounding like a sociological report? An example: the novel Affliction is told from the point of view of a minor character. The main character is Wade Whitehouse, and his brother Rolfe, his younger brother, tells the story. He only gradually implicates himself over the telling. It’s an unreliable narrator.

In some ways he’s the worst person to tell the story. And in some ways…

[Laughing] He’s the academic in the family…

He’s coming back to a town he doesn’t know anymore, with anger and hostility and sibling rivalry.

Repressed.

But he’s also the perfect person to tell the story.

Yeah. He has the tools for it. Unlike Wade, who is half drunk half the time. And violent.

When in the writing in Affliction did you feel like it was Rolfe telling it? Did you start that way or did you find yourself suddenly going, Oh wait a second I’ve got to tell this story from the point of view…?

When in the writing in Affliction did you feel like it was Rolfe telling it? Did you start that way or did you find yourself suddenly going, Oh wait a second I’ve got to tell this story from the point of view…?

Well, actually, I tried telling it first from Wade’s point of view, in the first person, and I got about a 150 pages into it and I realized how I was in a kind of lock down. I couldn’t really get any perspective on the story. It was so limited by his perspective on it. And part of the point of the story was that he didn’t know his own story. He didn’t know his own truth…until very late. So I threw that out, threw the 150 pages out, and invented the brother Rolfe. And I also realized that I was writing about alcoholism. In a family there is often an equal and opposite reaction to alcoholism. Wade was one reaction, which is to replicate the parental disease in a sense and to duplicate his father’s experience in the world. And the other is to run as far from it as possible. That’s why the children of alcoholics either become drunks or teetotalers. And Rolfe moves in the opposite direction…as far as possible. And it was partly that…just, you know, psychological realism…but also it was literary, too, coming up with a character whose perspective on the story was both intimate and distanced. And that’s sometimes the most difficult narrator to find.

And Cloudsplitter is a similar situation. You have to tell a story based on the life and times of John Brown, based on …well, John Brown is such a heat-seeking missile that you really don’t want to get too close to him. And he’s not going to tell his own story; he’s going to try to convert you. [Laughs] But if I get someone close to him, who is intimate, like his son, who was present at all the major points in his life, but who is also distant because he’s…

He has mixed emotions…

Yeah, he doesn’t want to get burned by his father. Then I can actually get to the story. So it’s not an uncommon strategy. At least not for me.

Well, I have been thinking a lot about this Obama-Romney circus we’ve been witnessing…

Haven’t we all.

…and about just how Balkanized we’ve become, and how we live in this first world bubble; and how so many people seem to move inside very narrow parameters, more and more so now. It’s become so easy to get caught in one little world…you know, from the golf course to the SUV, back to the gated community, all the time on your cell phone…

And I feel that in your fiction on the whole you’ve been pointing out ways that we’re socially alienated in the world…first world, second world, third world…but also you seem to be very consciously trying to throw together people who blur those lines; you put people together, or force two people who normally wouldn’t interact…because of the consequences of actions earlier…Like in Continental Drift, how Bob Dubois makes choices and drifts to a certain place and all of a sudden finds himself inside an illegal world he didn’t expect to be in. And thus his life converges with that of this young woman from Haiti and her son.

I can go through most of your books—most recently the Professor and the Kid in Lost Memory—and in each I see this kind of confluence, or forced encounter, if you will. Are you consciously trying to bring different people together over class and race lines? I’m thinking of Rule of the Bone and I-Man, this old Black man from Jamaica and then this kid from New Jersey…

Well, I’m not that conscious of it. It’s not a program or certainly not an ideological choice, or a consciously political choice. I mean everything is political in a sense; all choices end up being political. But I don’t have a program, and I don’t have an ideology that drives it. It’s a matter of following what is most mysterious to me. For me, writing fiction is a way to penetrate a mystery about humanity, about human life, that I couldn’t otherwise penetrate, that I couldn’t get to any other way. It’s only through the rigors and the discipline, the traditions, and the years of solitary work writing a novel…[Laughs]…or of writing fiction, that I can penetrate mysteries of human existence. I try to seize on a particular mystery, and I pass through it and come out on the other side. And of course there’s always a further mystery. That’s in a way the beauty of it: you penetrate one in order to open up another. So that’s what I am doing. I just don’t get certain things out there, and the only way I can get it is to go into that world, create a fictional world that will allow me to live there in a way I can’t in my day-to-day life…

Say, with Cloudsplitter and the convergence of religion and violence in American history, right up even to today…principled violence in the name of religious commitment and loyalty and faithfulness. Hard to get.

Righteousness.

Righteousness.

Righteousness, yeah. But this an ancient American…ancient human…but a particularly American crossroads, and I don’t get it, I don’t understand it, until I can spend six years of my life, as I did writing that book, up close and in the face of a John Brown or of people like that, associated with him.

And that’s only possible for me through the writing of fiction. I mean, I can understand it sociologically, and I can understand it historically and politically, but not in a deeply human way. The thing about a novel, and in fiction generally, but more particularly the novel is that it makes significant the inner subjective experience of a human being that you can’t see—or “perceive” I should say—and can’t enter in any other way—that profoundly subjective adventure that a novel permits. And almost no other art form allows…not theater, film…

Certain films, maybe, some auteur flicks…

I don’t think they do, partly because they are over too soon. It’s only two hours. If they lasted fourteen, eighteen hours maybe you might get inside a character deeply enough… [Laughs] You know a novel takes eighteen or twenty hours or more to read. And you spend that much time inside somebody else’s head other than your own. And it starts with the whole history of the form, it starts with Don Quixote and comes forward…It’s unique in that sense. There is no other form…epic poetry doesn’t do it…nothing else does it…

Virgil might be one of the first…

Yeah, but even so, you’re not really inside. You still have got that heroic template.

You make a distinction between the novel and the short story…mainly about length…but can you say a little about the differences between writing a novel and a story? And by that I mean the ways the act of writing the two forms feel different…

Switching from the novel to the short story is more than making a formal switch. You’re using different parts of the brain, it seems. With the short story it’s the part of the brain that makes music and writes poetry. With the novel it’s the part of the brain that links causes and effects together in chains. Of course, there’s a certain amount of overlap at the edges. Also, the short story and the novel have utterly different, almost opposite, relations to time. With the short story, you need to be able to remember the beginning when you get to the end or the story won’t make sense. Just as with a lyric poem or song. With the novel you need to forget the beginning, the sooner the better, so that the fictional reality is able to imitate the flow of time.

Last night you were talking about the more you write and the longer you’ve been a writer, the more proficient you get. In some ways you’re saying it’s harder to surprise yourself. Can you talk about that a little?

Yeah, but we were also drinking wine then so…

It sounded so good.

[Laughs] It sounded great then…Well, I’ll tell you, I think what I was trying to get to, when I was young…I am sitting here with Jeff Davis, we were all young together at Chapel Hill in the 60s and we were all beginning then…and it was so easy for me not to know what I was doing, because I really didn’t know what I was doing, and I couldn’t know. But that was so necessary to writing in a serious way. I didn’t realize that at the time. But I do now, looking back. It isn’t that I was stupid or anything. I was just tumbling into this enterprise, into this work, this process, without any real foreknowledge of how to go about it. But that was what made those early works—the ones that do—work…as art, as literary art. And then as I grew older it became increasingly difficult for me to recreate in myself that state of not knowing what I was doing. But just as essential, nonetheless.

Now I’m seventy-two and I’ve got a list of books here and I can say, well, I can guess I know what to do if I’m going to write that kind of book….or rewrite that story I wrote twenty-five years ago, and so on. I think I can write it again. But if I do, that’s all it is, just a clone of an earlier work. It doesn’t penetrate any mystery. It just demonstrates mastery, and that’s a different thing altogether. And so as I’ve gotten older it’s gotten harder to not know what I’m doing. It’s the only difference between when I was writing when I was twenty-five years old and writing in my seventies now. I now have to play a complicated set of tricks on myself in order to reach that point where I don’t have a clue what I am doing. [Laughs.]

- Continue reading Matthews’ interview with Banks. Here is Part II.

Sebastian Matthews is the author of a memoir, In My Father’s Footsteps (W.W. Norton & Company, 2003), and two poetry collections: We Generous (Red Hen Press, 2007) and Miracle Day (Red Hen Press, 2012). Having recently completed a third book of poems, Matthews is hard at work on a novel. He graduated from The University of Michigan back in the early nineties, heart-broken that the Fab Five failed to win it all.

Sebastian Matthews is the author of a memoir, In My Father’s Footsteps (W.W. Norton & Company, 2003), and two poetry collections: We Generous (Red Hen Press, 2007) and Miracle Day (Red Hen Press, 2012). Having recently completed a third book of poems, Matthews is hard at work on a novel. He graduated from The University of Michigan back in the early nineties, heart-broken that the Fab Five failed to win it all.