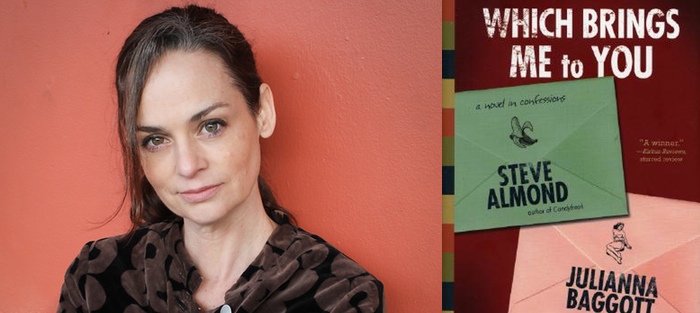

I came across Roxane Gay’s 2012 interview with Julianna Baggott in The Rumpus in the fall of 2013. In it, Baggott described her use of not one but two pseudonyms as an author (Bridget Asher and N.E. Bode), and I was curious by the apparent ease with which she shifted genres and readerships. I had just finished her apocalyptic bestseller Pure (Grand Central Publishing, 2012), which was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year and an ALA Alex Award-winner, and was excited to move onto the next two books in the trilogy: Fuse (2013) and Burn (2014).

In the fall of 2012, I had interviewed Russell Banks on Jeff Davis’s radio show, Word Play, while Banks was in Asheville as a Visiting Writer for Warren Wilson College’s Harwood-Cole Lecture Series. That long-form conversation was later published here on Fiction Writers Review as a two-part interview. I’d always enjoyed reading the long interview, and after doing one with Banks, I was curious what it would be like working with an author whose work was relatively new to me.

As with the Banks interview, I wanted to approach Baggott’s work and her ideas through the lens of working on my own novel: I wanted to ask her questions I was asking myself or wanted the answers to. And I needed a reading project to kick-start the next stage of revision on my book. However, unlike Banks, who I knew personally and had been reading since I was a teen, and whose few books I hadn’t read I could cover fairly quickly, I’d not read any of Baggott’s novels (let alone Asher’s or Bode’s!) with the exception of Pure and Which Brings Me to You (Algonquin Books, 2006), a novel she’d co-authored with Steve Almond. Needless to say, with more than twenty books to Baggott’s credit under one name or another, I had my work cut out for me.

I first wrote Julianna in early December of 2014. I asked her if she would be interested in talking about the span of her writing career (so far) as well as the ways in which she writes across different genres. Julianna wrote back that day with an enthusiastic “Let’s do it!” We jumped into the interview almost immediately. She sent me a box of her books, and I ordered a bunch more. Except for one phone call relatively early in the process, our conversation played out entirely through email. When the interview wound down in late April of this year, I was shocked to see we’d produced over 20,000 words (about seventy pages). It then took about a week for us to boil that down to 15,000 words, which represents a total of about fifty pages. And FWR has generously agreed to host this conversation, which itself will be published in five parts during this week.

In terms of her biography, Julianna Baggott began publishing short stories when she was twenty-two and sold her first novel while still in her twenties. After receiving her M.F.A. from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, she published her first novel, Girl Talk (Pocket Books, 2001), which was a national bestseller and was quickly followed by The Boston Globe bestseller The Miss America Family (Atria, 2002), and then The Boston Herald Book Club selection, The Madam (Atria, 2003), an historical novel based on the life of her grandmother. Her most recent Julianna Baggott novel is Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders, which came out in August from Little, Brown and Company.

The Bridget Asher novels, published by Bantam, include My Husband’s Sweethearts (2008), The Pretend Wife (2009), and The Provence Cure for the Brokenhearted (2011), as well as All of Us and Everything, which will be released in November.

In addition to the titles mentioned here and those such as the Pure trilogy noted earlier, she has written numerous books for young adult readers under N.E. Bode. Please visit her website for a complete list of titles and more information: http://juliannabaggott.com/

Finally, Baggott also has an acclaimed career as a poet, having published three collections of poetry: This Country of Mothers (2001) and Lizzie Borden in Love (2008), both of which were published by Southern Illinois University Press, as well as Compulsions of Silkworms and Bees (2007), released by LSU Press.

Editor’s Note: To begin with Part I of this five-part conversation with Julianna Baggott, click here.

Interview:

Sebastian Matthews: Your book The Anybodies (HarperCollins, 2004), written as N.E. Bode with illustrations by Peter Ferguson, starts off very much in the Harry Potter vein—with a young girl misplaced in a boring family, surrounded by magical signs burgeoning all around her, then visited by a mysterious person ready to take her off to a new life of adventure. The narrator brings up Potter, as well as many other children’s classics, throughout the book. How does one write such a book in the Age of Potter? How intense the anxiety of influence?

Julianna Baggott: I think that one can know (in retrospect) how a bestseller came to be when they look at what the publishing industry was creating a hunger for—because of its absence. When J.K. Rowling’s novel came along, there was little in the adult publishing world that was magical—except a few magical realists; mainstream publishing was really after contemporary realism. I think that one of the reasons Harry Potter took off—aside from being brilliant—was that once it hit the adult audience, through their kids, it swept through an arid forest, a wildfire. After that, a few things happened. First of all, literary novelists could write for children—Isabelle Allende, Walter Moseley, Michael Chabon, etc.—and simultaneously more magical novels for adults popped to the fore. For example, I don’t know how well The Time Traveller’s Wife would have done in-house pre-Potter. Years later, it’s okay if a novel that I pitch to an editor has a magical and/or whimsically possibly magical twist. Not as true when I started out. These twists or light sci-fi conceits weren’t welcomed, generally, with open arms.

Julianna Baggott: I think that one can know (in retrospect) how a bestseller came to be when they look at what the publishing industry was creating a hunger for—because of its absence. When J.K. Rowling’s novel came along, there was little in the adult publishing world that was magical—except a few magical realists; mainstream publishing was really after contemporary realism. I think that one of the reasons Harry Potter took off—aside from being brilliant—was that once it hit the adult audience, through their kids, it swept through an arid forest, a wildfire. After that, a few things happened. First of all, literary novelists could write for children—Isabelle Allende, Walter Moseley, Michael Chabon, etc.—and simultaneously more magical novels for adults popped to the fore. For example, I don’t know how well The Time Traveller’s Wife would have done in-house pre-Potter. Years later, it’s okay if a novel that I pitch to an editor has a magical and/or whimsically possibly magical twist. Not as true when I started out. These twists or light sci-fi conceits weren’t welcomed, generally, with open arms.

So. There’s that. Now, for me personally, Potter signaled that I could go back to my roots, which were magical realism. I didn’t yet think I could write it for adults, but I did think I could write it for children. And I loved that freedom, very much. I’d say I owe as much to Rowling, though, as I do to Marquez and Fred Chappell and Lewis Nordan.

Now, as for the premise you mention, these elements are certainly not Rowling’s terrain alone. The magical portal, the oracle who tells you the truth of who you are—these things are true of children’s literature in age-old ways. In fact, the reason there are so many orphans in children’s literature goes to the root of the writers’ first burden when writing for younger audiences—to make sure that the children in the book are the agents for their own change. If they have parents, this becomes much, much harder. And if the children are often pointing their point of view camera lens at adults, then you’re usually looking at a novel for adults told through a kid narrator—not children’s literature at all anymore. At the time, I was told that I’d ripped off Snicket (originally an adult novelist under his own name Daniel Handler) because of the direct address; but of course we both have Jane Austen, the Greek chorus, and many others to thank for that.

And, okay, I’m getting closer to your question. The specific note to Harry Potter is in a feminist rant early in the book. I’m stunned they let me keep it, to be honest. But I’m very glad they did.

I should also note that the point of The Anybodies Trilogy is that it’s a book about books, a book that loves books, and so there are, I believe, thirty-nine or so references to other works of children’s literature scattered throughout it. It is a trilogy that’s really an homage to so many who came before me. In short, maybe I embraced the anxiety of influence and turned it into a motor that propelled the series.

In The Anybodies you create a narrator who talks directly to the reader—always inside parentheses—and tells them about her horrible writing teacher and lets them in on her struggles with writing the book. Can you say a little about how this narrator—and this device—came to be?

First of all, I didn’t think of Bode as male or female until after writing the book. We had to craft an About the Author note and it required a pronoun. I picked male, but only because it felt slightly less incorrect than female. Both felt wrong. I’ve since come to embrace Bode as a young man.

I don’t know where Bode’s personal nemesis—his insanely jealous creative writing professor—came from, but it just kept growing and growing. It’s something that kids very, very much related to, and certainly something that hit-home for me in many ways. Not that I really had someone like this in my life—but there’s a cumulative specter.

I have a novelist friend who talks about “amplification,” which she defines as the places in the book where the reader can hear or sense the writer speaking behind the narrative point of view, informing and amplifying the novel’s main themes. These are places where the writer asks the reader to willfully suspend disbelief in order to receive essential knowledge from the writer. It’s risky business, of course, but there’s a certain expediency to it. Do you find yourself employing this technique in your novels?

I absolutely loved writing as N.E. Bode. In addition to the novels, I also wrote many “essays” as Bode for XM Radio. He’s absolutely addictive for me in voice. And I would sometimes find myself halfway through writing a letter in support of a colleague’s tenure only to realize it was Bode and not acceptable at all. So when I was under the gun and asked [my husband] Dave to step in for me one day to write a radio piece in Bode’s voice, I was even more stunned how naturally the voice came to him. It came so naturally in fact that I realized that my Bode voice was sometimes me doing a voice that belonged to Dave—who’s very funny and early on did some (short-lived) stand-up. So Bode is this strange version of a voice that rose up from us—both of us.

I absolutely loved writing as N.E. Bode. In addition to the novels, I also wrote many “essays” as Bode for XM Radio. He’s absolutely addictive for me in voice. And I would sometimes find myself halfway through writing a letter in support of a colleague’s tenure only to realize it was Bode and not acceptable at all. So when I was under the gun and asked [my husband] Dave to step in for me one day to write a radio piece in Bode’s voice, I was even more stunned how naturally the voice came to him. It came so naturally in fact that I realized that my Bode voice was sometimes me doing a voice that belonged to Dave—who’s very funny and early on did some (short-lived) stand-up. So Bode is this strange version of a voice that rose up from us—both of us.

That said, Bode’s voice—that direct address I mentioned—is a great tool. It allowed me so much agility as a writer, which was also a reason I found writing as Bode so liberating.

I feel a little like a fan asking a magician to give away their secrets, to share how they accomplish their tricks…but I am curious, in a story such as The Anybodies, are you writing straight from your imagination, making up things as you go, trusting that things will come around in the end—that the butterfly that appears in the opening scene will show its true identity to you later—or do you have much of the story already mapped out? I guess another way to ask this question is: have you thought through the story fully before writing it down or is the story transforming under your typing fingers? Or is it a little of both?

Many of my books are voice. If I find the right voice, I’m in. Still, I don’t get out of knowing where I’m headed. I write maps, yes—on big sheets of art paper or, as it is right now, on the back of Christmas wrapping paper taped to the wall. The map allows me to take what has no physicality—a story in my head—and make it manifest. In this way, I can find holes and saggy bits. I can get a bird’s eye view. Easy to do in other professions but not ours. So yes, I map.

If you look at the definition of flow, you’ll see that it’s more likely to happen when skills meet a challenge that is tough enough but not overwhelming. In writers—or many kinds of creators—we set the challenge but can only kind of heft it up as large and complex as our skills allow (as a general rule) because one of our main skills is figuring out a large complex plot to begin with.

I have a friend who says she writes for her life. I have another who sees himself keeping sane through his writing (which I think is true for a lot of writers). I find that writing helps balance my life. Why do you write? Where do you write from?

As I mentioned, I was hauled to a lot of plays as a kid—I mean a startling number. And I loved them. I am not a writer inspired to emulate (as Doctorow puts it) although I certainly learned to write by way of other writers. My impulse is to tell a story, and I’d have found ways to do this if language didn’t exist. I’m deeply human-centric. I’m barely aware of what I’m eating or amazing scenery or incredible music if I’m talking to other humans.

But none of this is answering the question. I write—or create—because it’s like breathing. Living (and reading and watching and witnessing…) is breathing in. Writing is breathing out. I’ve written many variations of answers to this question. But I’m going to give one I never really give.

But it’s no longer that simple. I have to talk about the things we’re no supposed to talk about. Writing is also a large part of how I make a living now. It’s part of my identity. It’s how I came to accept the word ambition. It’s how I’m of use to others. It’s how I compete. (I’m deeply competitive. I mean, a few years ago, I had to really stop myself from competing with strangers when we were both descending stairs because, in my head, I was trying to beat them to the bottom.) It’s how I turn my jealousy into something positive. It’s definitely how I envision digging my way out. Out of what? That’s not important. It’s simple the means. It’s some promise of salvation or change or possibility—in both artistic and practical ways. Look. I was an athletic kid but very small. I was the fastest girl in my middle school; granted it was a small Catholic school, but still—boys and girls. I was tiny and I could do the longest standing broad jump. I’d also been raised among adults—the youngest of four after a considerable gap—and so I was annoyed that I couldn’t always be part of that adult world of conversation. I felt underestimated most of the time. Don’t get me wrong. I wasn’t academically gifted. I wasn’t brilliant. I was simply used to being a grown up and discussing complex playwrights and actor’s monologues. My mother was also telling me stories throughout my childhood—Southern Gothic tales that happened to be true, our family history—stories I certainly shouldn’t have heard, and yet I’m so thankful for them. My father was a lawyer who loved to argue—politics, religion… It was a very verbal family environment, one that showed emotion—vividly. I’m just not going to lie to you here and say that my desire to write is purely about some artistic ideal. It is a long marriage with the page—a beautiful, complex marriage. But my inner monologue—the one that kicks in when I think someone doesn’t believe in me, doesn’t think I have what it takes—that is one trash-talking, locked-in, hyper-motivated voice. I love that space. I can’t exist in it for long, of course, but when that opportunity arrives and the voice kicks in, it’s a rush. It goes all the way back to my childhood and it is some elemental version of myself I rely on. I’ll tell you another thing—this voice believes in the people around me, too. And sometimes I go deep for someone else, using this voice to help lift them up. When I believe in you, I won’t let you give up on yourself.

In a 2011 interview in Pif Magazine, conducted by Derek Alger, you were asked about the origin of Which Brings Me to You (Algonquin Books, 2006). You said: “The tagline ‘A Novel in Confessions’ came to me. I thought it’d be cool to write it with a male writer. Steve Almond was my first choice. He said no. I said, ‘Great. I’ll send you the first chapter.’” It’s as if you chose him to be your audience…

In a 2011 interview in Pif Magazine, conducted by Derek Alger, you were asked about the origin of Which Brings Me to You (Algonquin Books, 2006). You said: “The tagline ‘A Novel in Confessions’ came to me. I thought it’d be cool to write it with a male writer. Steve Almond was my first choice. He said no. I said, ‘Great. I’ll send you the first chapter.’” It’s as if you chose him to be your audience…

Genre is just another word for audience. It’s why poetry doesn’t further break down even though it holds as many genres as prose. I wrote The Anybodies for my previous self. I wrote Which Brings Me to You with Steve as the sole audience—as my character wrote solely to his character. These limitations helped me immensely.

Which Brings Me to You is such a fun read, such a cool conceit. You guys obviously had a blast writing it. Just curious, but hasn’t anybody tried to make a movie of this? It seems like it would make a fantastic Rom-Com…

Which Brings Me to You was optioned for years. We’ve had great actors (Bradley Cooper, Kate Winslet…) attached over the years and some wonderful directors. There’s a screenplay adaptation written by playwright Keith Bunin that’s really brilliant. To be honest, I don’t currently know where the producers stand. A lot of close calls.

Did you write out these confessions as they came to you, creating a life confession by confession, or was there a point (at the start or in the middle) where you diagrammed out your characters backstory?

We were true to the book, flying blind. I knew things about my character, of course, but nothing about his. And I wouldn’t write a confession until I got one from him. The pattern of Jane and John is exactly the one we followed.

I am curious how the revision process went. Did you revise or edit each other’s sections, just your own, or both? Did you rearrange the order of the confessions or make any suggestion back and forth about subject matter, tone, etc.?

After Steve said yes to the project, he rewrote a bit of the first chapter to make it feel like his own. By the time we got to the ending—which Steve wrote—we weren’t quite on as good of terms. I had the opportunity to note a few things… Basically, we started out very strong—back and forth, like a tennis match. It was really fun. We’re both fast writers and it was fun. But then, at a certain point, things broke down. I had an edit—a strong one; he accepted it, but it was hard. Slowly, the characters were sock puppets for various problems that we had with the work at hand. At a certain point, I suggested we give up. We both had enough for the bones of a great novel of our own. If nothing else, hey, we’d gotten each other this far. In short, I was suggesting we each take our toys and go home. Steve was the one who kept the book together. And I’m thankful he did because the book was better for our arguing. The characters needed the conflict.

Then, of course, there was an editor. She made some suggestions, smart ones that broke up the epistolary form a bit. She then edited Steve’s sections and gave those edits to him, and gave edits on my sections to me. All in all, it was tough and, by the tour, we were friends but we didn’t sit next to each other before boarding or on the plane. We sprinted through a few airports together and took cabs together, and we were, you know, in good spirits, but it wasn’t like two pals, you know. And then there was this hotel in Seattle that mentioned that at four pm, they were offering a customer appreciation event on one of the floors. We were both tired, went to our rooms, and then I decided to head down to the event. It was glorious: a pyramid of cosmos, a room just for cheese, a circular shellfish bar. It went on and on and was obviously meant for their corporate events-planning customers. I called Steve and left a message. “Get down here. Now. This is amazing. I can’t believe what I’m seeing…” This kind of spread—better than any wedding I’ve ever attended—is a rare gift. Whatever conflicts we might have had at the time, this trumped all. If one thing unites writers it might be free food and an open bar.

How did your readers respond to this book?

People who loved it, loved it passionately. As I recall, we took a beating for the fact that it was epistolary and that two random people shouldn’t actually be able to write as well as we did. In point of fact, both of the main characters are writers—John wrote funny ad copy for a living and Jane had published a book on feminism. In my mind, I was aware of the literary conventions that allow for the first-person—even in letters—to use the conventions of fiction even if they wouldn’t normally appear in a letter—things like scene, dialogue… But I actually feel the erosion of many literary conventions; readers aren’t as aware of them as reviewers and critics have been in the past, and all readers now have the option to be reviewers and critics. So some books will get roughed up a bit for this reason; I’m partial to many literary conventions because I want the goods of scene and dialogue and access to heart/mind beyond filter of language, etc.

Editor’s Note: Return tomorrow, when we’ll publish Part IV of Sebastian Matthews’s five-part interview with Julianna Baggott. Part IV will focus on being prolific, writing practice, and working on more than one project at a time.