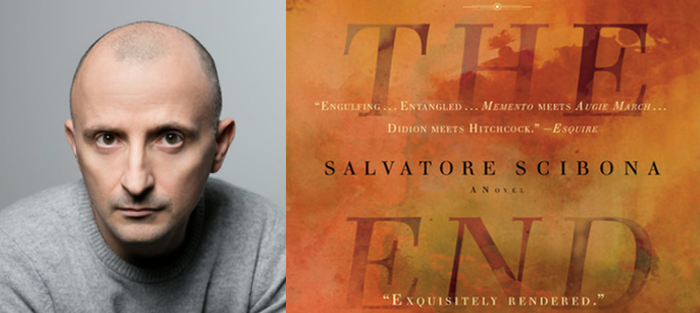

Salvatore Scibona grew up in Strongsville, Ohio, a southwest neighborhood of Cleveland. After graduating from St. John’s College in 1997, he went on to the Iowa Writers Workshop, where he received an MFA in fiction in 1999. Scibona spent the next year in Italy on a Fulbright scholarship, and in subsequent years he earned fellowships from the Copernicus Society of America, MacDowell, Yaddo and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. Scibona’s writing has appeared in the Threepenny Review, Best New American Voices 2004, The Pushcart Book of Short Stories: The Best Stories from the Pushcart Prize, The Pushcart Prize XXV: Best of the Small Presses, Provincetown Arts, and News from the Republic of Letters. He lives in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where he works as the writing coordinator at the Fine Arts Work Center and teaches fiction during summer sessions at Harvard.

Last fall Scibona’s debut novel, The End (Graywolf, May 2008), was selected as a finalist for the 2008 National Book Award. On March 16, the New York Public Library selected Scibona as the winner of the 2009 Young Lions Fiction Award, which recognizes innovative contemporary fiction by American writers 35 or younger.

At the center of The End is a crime around which the lives of its six principal characters orbit. The novel opens on August 15, 1953, on the day of a street carnival in the Italian immigrant community of a Cleveland neighborhood, Elephant Park, and moves back and forth throughout seven decades, eventually returning to the day of the carnival. Valuing thematic resolution over narrative resolution and featuring a lush, idiosyncratic prose style that burrows into the subjective experience of each of its main characters, The End has drawn comparisons to the works of modernists such as Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner, and Gertrude Stein. In a starred review, Publisher’s Weekly referred to The End as “part novel, part epic prose poem,” calling it “a literary tour de force.” The End will publish in paperback from Riverhead this fall.

Interview:

Michael Hinken: How did your time as a fiction fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center contribute to your growth as a writer?

Salvatore Scibona: Before my fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center, I had a Fulbright Fellowship in Italy to do research for the novel. I had never been outside the country before and could hardly speak Italian. I was there completely on my own and had no structure in my life, no institutional limitations. I kind of lost it. I was too young to do that, and it was hard on my work in the short term. Once I got home, I took some time to evaluate what I’d been doing, how I was doing it, and I saw how important it was for me to structure a day. So when I got to the Fine Arts Work Center, I benefited from that lesson about structuring my time. The Work Center in that sense was a do-over.

What about going straight from undergrad to an MFA program? Do you recommend that route for young writers?

What about going straight from undergrad to an MFA program? Do you recommend that route for young writers?

There are disadvantages for some, but for me it worked perfectly. When I got to Iowa I had sloppy, unfixed habits, and I was surrounded by older people with much better habits than I had. I was there at the right time: old enough to want guidance, but young enough to take it.

During the introductory meeting there, Frank Conroy gave us all a single piece of purely practical advice: write for at least three hours, in the same place at the same time, six days a week. I had already failed as a writer in a billion ways. It wasn’t as though I already had a suitable system; so I was eager for that kind of advice, and I took it. If I had gone to an MFA program when I was thirty, I would have had my own way of doing things and it would have been harder for me to start afresh.

The change it made was that I started writing less out of discipline than out of habit. Discipline is determined by the superego. It’s continually reinforced by self-punishment and threat. Habit, on the other hand, is internalized experience and doesn’t need that harsher wasteful force that discipline employs. Habit, like instinct, is vastly more efficient than discipline because there isn’t the constant input of energy to make you stop. Writing purely from discipline is like driving on a superhighway in a car with an automatic transmission but still using both feet on the pedals. You’re constantly stopping and going, and sometimes you make the clumsy mistake of stepping on both pedals at once, telling the car to stop and go at the same time. Good habit uses only the one foot. If you want to go slower, you just ease off the gas; you only hit the brakes when you really, really need to stop.

My habit goes like so: I wake up. I have my oats, I drink my coffee. I go to the desk. This morning, for example, I didn’t have a special desire to go downstairs to my studio and write, but I’m so much in the habit of going there that I did it anyway.

I understand you had some help forming those habits.

Right. When I got back from Italy, I lived in New York and worked a terrible job. I was trying to write after work, but I’d leave for the office by eight in the morning and come home at six, eat dinner, run errands. It was ten p.m. before I got to my desk to write. I was just too tired. Around that time, a friend of mine, the novelist Joe Monninger, advised me to start paying myself first—that is, to write in the morning before I left for the job.

So then I was trying to wake up in the wee hours and write, to pay myself first, but I’d gotten inured to the alarm and kept sleeping through it.

Now, around this same time, my mother in Ohio had insomnia; she also had a lot of unused minutes on her cell. So we set up a system for a few months (I should be ashamed of this), whereby she would call me in New York at four-thirty in the morning. And the phone was in another room of the apartment, so I had to get out of bed to make it stop ringing. Once I’d found the phone in the dark, I would say, “Okay, I’m up.” Then I’d put on some clothes and type.

After a few hours, the sun would come up. Outside, across an empty lot, a building presented thirty or so separate apartments, and every morning I watched the lights go on in them one by one, and partly naked people coming to the windows and looking out at the rubble and the weeds in the lot, while I typed.

You seem like a man who likes a system.

Well, yes. But the question isn’t whether you have a system—we all have a system, we all spend most of our time repeating previous patterns because it would be too excruciating to have to be thoroughly conscious of the free choice implied in every step we take on the street. The question is whether we have mindfully chosen our system, and whether the system works.

Notwithstanding what I said about discipline, a writer’s system still has to involve certain austerities. For example, if you’re a successful lawyer, you might be used to an income that provides you a new car every two years, a house of a certain size, wine of a certain quality. But you are paying for that with your seventy hours a week at the office. Not many writers can afford a taste for fancy things. And it’s a taste for those things that can keep the lawyer in his job—that is, keep him from writing if he wants to—because he thinks he needs them, when he’s only used to them.

Better not to develop the taste in the first place. Better to have a system that puts those things aside as a matter of course. If you don’t aspire to riches, you won’t miss them. Grace Paley’s famous two-word advice to young writers was low overhead. Writers can’t afford habits that feed a desire for material possessions. Affluence is too expensive. It costs time.

What have you been working on since the novel has been published?

“Speak not, lest we break the spell.”

Okay. What have you been up to lately?

I just built a worm farm: a pound of worms, living in a wooden wine crate. They eat twice their weight in a week. They eat eggshells, coffee grounds, leaf mold, banana skins. And they shit dirt.

Is there a writing metaphor in there?

Probably. Agriculture puts a sail to the winds of my unconscious. I’m fascinated by seeds, farms, worm farms, sourdough starters (which are in effect bacteria farms). Last night I couldn’t sleep because I kept worrying about this sourdough starter in the fridge. I had to get up and look in on it. I couldn’t not think about it. I had to fuss with it. Writing comes from a similar place.

After my book was published, I needed a transitional object, as they say. I started a garden. I pet the plants. I will admit that. I talk to them. I try to encourage them.

How does that degree of care and attention translate to your writing, exactly?

I work like this: I write longhand, then I type what I’ve written on a typewriter. Then I revise with a pencil, retype, revise, retype, and so on over several years. Finally, I enter the thing into a computer. The computer is where it goes to die.

To my eye, if a piece is typewritten, it’s still growing. On the computer, and especially on the laser-printed page, which looks so much like it’s been set into type, it seems finished. It loses its elasticity.

When I retype a sentence on a typewriter, I make decisions, at least quasi-consciously, about every word and piece of punctuation. On a computer you’re only amending something that already exists. On a computer, you only have to be conscious of the change you’ve decided to make. You don’t have to think about the rest of the sentence. When you retype the sentence on the typewriter, you’re re-examining every word and comma, investing yourself in the entire sentence again.

Let’s talk about The End. You mentioned once that you began writing the book by trying to describe the sound of a man’s footsteps on a staircase. Is that still in the book?

Yes. But moved to a different context. It’s the part when the jeweler is climbing the stairs after his night of humiliation, when he hears his self-solemn footsteps. At first I had only wanted to describe that sound, you know, what a man’s flat foot sounds like on a step. Then what? What’s at the top of the stairs? A door? What’s it look like? What’s behind the door?

This sounds like writing as an associative process instead of one that you can order and control, say, by using an outline.

Writing from an outline is like going to the furniture store of the mind and taking from the shelf a chair constructed by the calculating, ego-driven, conscious mind, and then letting the unconscious have the high privilege of painting it.

For a piece of fiction, that is precisely wrong.

The unconscious mind should be generating the material, turning the spindles and designing the whole thing according to its weird, buried ambitions. And the conscious mind should come in to manage and govern that process.

To me, outlined work has a genre-ish feel. It is literally generic: it starts from the general and proceeds to the specific. I don’t like to work that way. I start off saying, “I want to describe that leaf. The leaf is green. What kind of green? What is the leaf doing?” It takes too much time, but anyway. It is a much less reliable process than the outline process, and I waste time writing chapters that only show their unsuitability late in the game. But I want to write a book made of elemental things.

Also, if the plot is predetermined by an outline, then the character’s freedom is bogus.

So do you ever outline?

When the need for conscious structure becomes irrepressible.

Speaking of structure, I was impressed by the structure in The End. But it also challenged me, thwarting my expectations after the first chapter. Specifically, I mean to ask about Rocco. Why does his story recede into the background after the first chapter? You mentioned once that you wrote that section last. How do you see it functioning?

I wanted it to be like a long piece of music. The melody is introduced early. Then the melody is repeated in different keys, with different instruments, until it works its way into the reader’s feelings. I wanted to prepare the reader for that kind of reading experience, and for a kind of musical conclusion. At the ending of the first movement in a symphony, the melody is held in suspension. It’s established but unresolved, and resolving it is the work of the rest of the piece.

After Rocco’s argument with the ice cream man at Niagara Falls, his faith fails him. I wanted the reader to think of that kind of crisis as the melody that the rest of the novel would play out again and again—a character coming to a crisis that shows her how unsatisfactory her previous hopes had been.

The book’s structure is not a slave to narrative. That’s true. I use narrative for this other purpose. I love narrative. But the ending is not the sort of ending we get in a romance (the hero either dies or gets married, to oversimplify). But I think it’s the kind of ending we get in life.

This isn’t new. Hector dies, near the end of the Iliad, but the real ending is when Achilles goes to sleep. The emotional arc of the story is that Achilles is enraged at the beginning, and by the end he has put his rage to sleep. It’s a story of an emotion that is brought to resolution.

How would you describe the emotion brought to resolution in The End?

When Rocco is having the second lunch with Mrs. Marini and the boy, and he’s

telling them about the train he took from New Orleans to Nebraska—to me that is the emotional navel of the book. Everything in Rocco’s life had led to that train. He had the sort of hope that comes from having pointed yourself at an idea that you now believe you are finally about to touch. And you are always wrong.

All the characters have their own version of that experience, a failure of faith, a disappointment.

What about the title? I’ve read some reviews that have suggested that the title is too large, too vague, referring to both everything and nothing at once.

The book has a lot of tentacles. So it was going to be especially necessary to make the title dense and blunt. But all the titles I came up with gave precedence to one part of the book over others—a day or place or character. I didn’t want that effect. “The End” distills the unifying spiritual dilemma of the book.

The End is dedicated to your grandparents. Why?

I didn’t come from the sort of culture that encourages kids to read for pleasure or enlightenment, or even for entertainment. All these things, it was implied, come from conversation. At which all four of my grandparents were expert. I was born in the same city as all my grandparents. I saw their pasts all around me. How could I have written about anyplace else? They were all alive when I started the book, and they were all dead by the time it was published.

I’m sure your grandparents would have been pleased with the National Book Award nomination. What was that experience like?

It was delightful in every way. Seven hundred people in black tie and sequined dresses eating fillets of beef in the former well of the New York Stock Exchange. Writers I had admired since high school begged their pardon as they made their way to the bar and the john. It was far more than I could properly take in. For the first time in my life, I felt obese.

What authors have influenced you?

George Eliot, Annie Dillard, Toni Morrison, Plato, the Bible, Virginia Woolf, Don DeLillo, Saul Bellow, Halldór Laxness.

I’m not conscious of influence so much as love. When I love a book, I remember deeply where I was while I was reading it, where on the page certain passages appeared. I fall in love with a writer and want to read all of that writer’s work. Right away.

What are you reading now?

Alternative Lives , a brilliant collection of stories by R.D. Skillings from the mid 1970s set in a town in Down East Maine. Also Madame Bovary and Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

, a brilliant collection of stories by R.D. Skillings from the mid 1970s set in a town in Down East Maine. Also Madame Bovary and Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

Some writers say they can’t read much when they’re writing. What do you think about that?

I think it’s a lot of nonsense. The solution is not to treat your voice as this fragile thing that needs protection from influence. The solution is to feed it influences. If you plant a seed in wet newspaper scraps, it will sprout and then it will die. It needs to eat a variety of things—manure, sand, peat, leaf mold. To stop reading while you’re writing is anorexic. (Aren’t you supposed to be writing all the time anyway?) You don’t train the mind by starving it. The same muscles are involved in reading as in writing, so when you read, the part of your mind that imagines and uses language and feels hatred and compassion for other people, both real and made-up—all these parts are on fire, and the fire makes writing possible.

I try to read some, work some, exercise some, socialize some. To be productive, I need all these things. Certain austerities are necessary. Others are a trap.

If you weren’t writing, what would you be doing?

I wouldn’t survive as a farmer, and yet . . .

And I will tell you that in the third grade, I desperately wanted to be the owner of the Cleveland Browns. But I try not to entertain other ambitions—not for longer than an afternoon. I know what I want to do.

Further Resources

Visit The End‘s official site, and read reviews of the novel from a wide range of publications.

Watch GalleyCat’s interview with Scibona at the New York Public Library’s 2009 Young Lions Awards Ceremony; you can also read more about the NYPL’s prize (which this year was presented by Ethan Hawke) in this P&W article.

Listen to NPR’s November 2008 Weekend Edition interview with Scibona.

Check out more of photographer Carlos Ferguson’s work on his blog.