A young boy, lost or possibly abandoned, weeps in a German airport. He doesn’t speak the language. He has no papers, no ticket, no name. Authorities and bystanders try to help. They ask questions, offer each other advice, scan the airport for someone who looks like they’re looking for someone. Nothing. How can they help? How the boy got there, where he’s going, who he is—all is obscured, swallowed up by the emergency of the present. He is nobody and he is inconsolable.

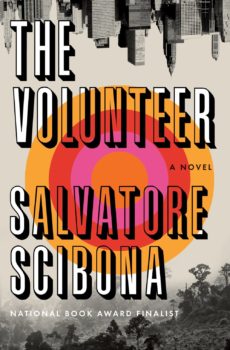

So begins The Volunteer, by Salvatore Scibona, published by Penguin in early March. The powerful opening scene is re-contextualized soon after, as readers are introduced to the boy’s father, Elroy, and learn how and why the boy has ended up alone in a foreign airport. From this vantage point in 2010, the novel then moves back in time to an Iowa farm in the late 1940s, and the story of the main character, nicknamed “Volunteer” by his parents, “Vollie” for short, begins.

Vollie’s story spans decades and transports readers from the farm to his soldiering life in Vietnam, to his shady dealings with U.S. intelligence stateside, to an almost-abandoned commune in New Mexico and points in between. As the story unfolds, Vollie sheds versions of himself, abandons earlier incarnations, and even gives up his name; while working undercover, he is called “Dwight Tilly,” and this name sticks. Eventually, the fate of the boy in the airport, Janis, becomes known, and this storyline intertwines with those of Tilly/Vollie and Elroy. The novel builds around the interconnected fates of these three characters, offering surprises along the way best left to readers.

A novel that seems concerned with the formation of the self, the capacity to become someone new according to place and circumstance, The Volunteer raises sticky questions about the very essence of the self. If we are always changing, then who are we? And if we cannot know even ourselves, then how can we know others? How can we love, or connect or feel responsible to each other, if we are unknown to even ourselves? If we are, in essence, a nobody?

And despite all this existential anxiety, the novel is interested, too, in connection. Despite the mystery of the self, its cycles of dissolution and formation, despite failures of love and care and responsibility to each other, the fates of Vollie, Elroy, and Janis are connected, sometimes in surprising ways. What happens to one seems to resonate in the life of another, something like the chain in Chekhov’s story “The Student”—when one side is struck, years later down the line, another feels the vibration.

The novel is difficult to paraphrase, as maybe anything artful should be. A lot goes on in between. In this way, Scibona seems less interested in shaping a life on the page, in bending a life toward meaning, and more interested in inviting readers to observe a life lived in all its complexities, its false starts and failures, its improbable reunifications and impulsive acts, its authenticity. Because of this quality, the effect is not tidy. Rather, the novel is teeming with life. Idiosyncratic, strange and beautiful, beautiful in its strangeness, a little random at times—that sort of life.

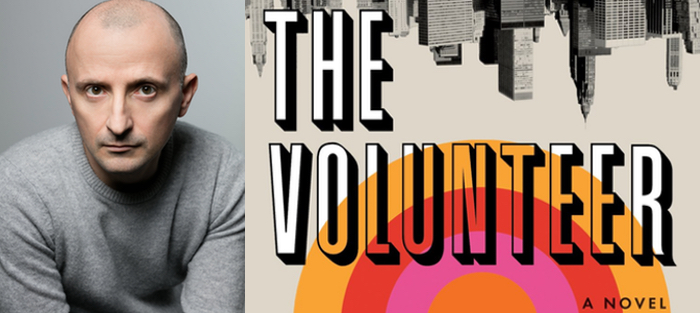

Scibona’s first novel, The End (Graywolf), was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2008, and in 2009 he was awarded the Young Lions Fiction Award. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Harper’s, and The Threepenny Review. He has won a Fulbright Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, an O.Henry Award, a Pushcart Prize, and a Whiting Award, and he has been a fellow at the MacDowell Colony and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. Scibona, a native of Cleveland, Ohio, is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and St. John’s College.

Scibona currently directs the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. For this interview, we communicated via email.

Interview:

Michael Hinken: Let’s talk beginnings. What are the origins of The Volunteer?

Salvatore Scibona: I had been working for a couple of years on a book about a character I still knew poorly. He was Midwestern, born in the middle of the century. I was stalled because I had so few particulars about him. I did, however, have a longstanding frustration with the self as a category, the conscious I that intervenes between our inner being and the world, also between our body and the world. This character was bearing the consequences of a choice to leave his self behind: how, practically speaking, would such a person live? But all this was too abstract.

Salvatore Scibona: I had been working for a couple of years on a book about a character I still knew poorly. He was Midwestern, born in the middle of the century. I was stalled because I had so few particulars about him. I did, however, have a longstanding frustration with the self as a category, the conscious I that intervenes between our inner being and the world, also between our body and the world. This character was bearing the consequences of a choice to leave his self behind: how, practically speaking, would such a person live? But all this was too abstract.

Then I had an experience very like the first two pages in the book: in a German airport, I encountered a child who for all anybody could tell had been abandoned there and was speaking a language no one could understand. His situation was a horrifying blow, most everyone waiting at the gate seemed to feel this way, visibly appalled and helpless to help him. I went down the terminal with him and an airline agent, checking the other gates for anyone who might be looking for him, but we found no one. Finally, the agent opened a door, and the two of them passed into the unsecure zone of the airport. I walked back to my gate, flew out of the country, and never saw him again. How had he gotten there, and what would become of him? These questions were lodged in my mind, but I had no way of answering them.

The contrast between the man in my book who wanted nothing but to disappear and this child asking to be found—the one imaginary, the other right in front of me; the one near the end of life, the other near the beginning—felt immediately like an important opposition. Something had come into alignment, a movement of bodies and shaping of light, as in an eclipse. The possibilities of the boy’s past and future and the version of Vollie Frade that was already on paper became entangled.

That the novel sprung in part from your abstract idea—something about the intervening self—coming into contact with the concreteness of life, a specific person, time and place, makes me curious about how place functions in your work.

A lot of writers starting out—anyway this was true of me—focus on idea, voice, or another of the standard elements of fiction, in an effort to go right at a story’s essence. Place seems mere background. The result is language that lacks a necessary particularity. The words slide around like dominoes getting scrambled.

Life isn’t like this. We are always in a particular place at a particular time. As much as we might want to treat our first observations as essential, they remain unreal until they are embodied. The story requires people, acts, objects. Once the essence takes physical form it naturally needs a place.

A writer may want to use detail to make the story real, but before she commits herself to a place, she lacks a criterion for the rightness of most of those details. Place usefully restricts the infinity of possible facts. Without it, accuracy is impossible. The story can’t pass an implicit reality test and drifts away in the reader’s imagination rather than landing there.

A place where my imagination landed in The Volunteer was the section when Vollie’s ex, Louisa, is on her own and finds herself, a little worse for wear, at a former motel apartment complex with a crabapple tree in the courtyard. Not to make too much of it, but something about that crabapple tree felt spot on, a part of the heartbreak of that place. It was an authenticating detail, a moment of recognition for me as a reader.

I like your phrase “authenticating detail.” The writer searches for the right word, but what makes it right? Flannery O’Connor is helpful on this subject, her discussion in Mystery and Manners of “loaded” detail. This is not the same thing as symbol. The practice of teaching children to read novels by asking them to look for symbols leads them into the demoralizing practice of reading a story as a code to be deciphered rather than a living imagined world. On the other hand, a writer can fall into description that’s dead to wider significance, what Frank Conroy called “abject naturalism”: the piling on of details that are accurate but don’t charge the story with meaning.

Good writing often finds a sweet spot between these poles, pieces of physical reality that have the charisma of fact (a charisma they get both from their accuracy and their seeming muteness) and that also paradoxically feel involved with the meaning structure of the book.

At the moment you mention, the narrator is borrowing some of Louisa’s mind in observing that the tree is “grateful to have endured.” Much of the rest of the description of the tree is physical. The tree is a tree, but I think it also holds something else. I read that gratitude as a quality the tree really does seem to possess but that we see only via an emotion that Louisa at the moment, in her modesty, is unwilling to confess she feels for herself.

The novel transports readers to a variety of places, seems always on the move. I would hesitate to call this a road novel, but Vollie spends quite a bit of time going from place to place, on the road.

In a previous draft, a woman had asked Vollie whether he believed in the Vietnamese myth of the wandering soul: that a person needs to be buried in his native land or his soul will never rest in the afterlife—i.e., that there is a permanent rightness to your home place. Tilly responded, “No, ma’am. God gave me feet to walk.” It is his nature to move. He always does so with an objective: work, love, defiance of those keeping him where he is. But the novel also implies that his freedom is at best incomplete.

On the point that there may be no permanent rightness to one’s home place, the novel seems concerned about the self, how it shifts, re-shapes according to circumstances. As comes up a few times in the novel, a person is composed mostly of the water they drink, and this water comes from a distinct place, has a distinct elemental composition, so in this way a person is of a place—both from a place and made up of this place, at least for a while. But new place, new water, new person, right? What drew you to this idea of transformation?

I don’t think I’m alone in experiencing the self as a cage and also as a fable we tell ourselves. We speak of “who we really are” as though we know what that means. The philosopher David Hume is penetrating on this question. He reduces the thing we call self to a bundle of sense impressions.

Notwithstanding what we know about water’s molecular structure, most of us still think of it as an element. As you say, it’s most of what we are. Without it, all our fancy notions of self are moot. Water needs no self to go on being what it is. The Volunteer of the title aspires all his life not to be someone else but to drop the pretense of having a self. To leave identity behind and live in the body, in the elements that compose the body. This comes at a cost, but it’s largely the people close to him who have to pay it.

To live in a body is to have a name. I was curious about the handling of names in the novel, the shifting names: Vollie/Tilly, the boy/Elroy, Janis/Willy. What was your thinking on names and naming?

A writer seeks the right word. The right word for a person, her name, is a unique category; a name seems to have a soul in it. People in the novel give names to each other for reasons that matter a lot to them. In the case of Elroy, as you mention, no one knows which of the men at hand is his father, and the people caring for him tell him he comes from the earth around him on the Heflin ranch, so they give him Heflin as a surname.

A writer seeks the right word. The right word for a person, her name, is a unique category; a name seems to have a soul in it. People in the novel give names to each other for reasons that matter a lot to them. In the case of Elroy, as you mention, no one knows which of the men at hand is his father, and the people caring for him tell him he comes from the earth around him on the Heflin ranch, so they give him Heflin as a surname.

Names have a terrible power. We are told not to speak the name of God in vain. A lover calls us by a pet name, and for anyone else to use it skeeves us out. Certain relatives might use a diminutive that no one in our adulthood uses; to be called by this old name is both comforting and destabilizing. It implies we can be reassumed into a past that we may long for but that we have in reality abandoned. And we may lose a name, as some of the characters in the book do, which can cause a rupture in the psyche that makes a complete return to previous life impossible.

In our continuing conversation about the self, I was interested in times when Vollie seemed to lose himself in something, whether firing the .50 caliber, lovingly named “Hog Butcher,” in Vietnam, or playing the piano, or even in falling in love with Louisa—in these moments everything seems to fall away but the present moment.

Vollie thinks the body wears a self like a jacket, and the jacket can be removed. Maybe he’s right. His experience of music contributes to this conclusion. It makes him feel that his body is a medium for something taking place outside him, something that has no need of him. I’ve had that experience too. The spirit catches you, and you fall down. An experience that is akin to grace, in religious terms, in that you don’t do it, it happens to you.

If grace is real, then seeking it is futile. It will not happen to you because you pursued it. Saul did not ask God to knock him off his horse. You can’t make rain fall on your head.

And yet you can go outside, you know? Someday somebody will explain this to me: the things that come to us only if we try, but that do not come to us by virtue of our trying.

Because readers get access to all three main characters in their childhoods, and because there are some resonating moments among all those childhoods, I found myself thinking of that line from Freud, “The child is the father of the man.” Any thoughts on how that concept operates in the book?

That idea goes back at least to Wordsworth, “The Child is father of the man / And I could wish my days to be / bound each to each by natural piety.” But I do love to read Freud, partly for his boldness at naming aspects of experience about which I had had no clear way of thinking because I didn’t have words for them.

Also, it’s bracing to watch him change his mind. Whenever anyone says, Freud said X, you have to ask when he said it. He is likely to have written beautifully later on about an important mistake in that earlier thinking. To read him is to have a vivid engagement with a problem that becomes more and more interesting as he ages.

One of the real pleasures of The Volunteer is its dialogue. I get the same impression from it as I do from reading dialogue in DeLillo, maybe Joseph O’Neill and Sergei Dovlatov. The dialogue is stylized somehow, slightly self-aware in that I as a reader am subtly reminded of its artifice, its construction. And yet, in these cases, I’m always 100% in the story, going along with it, drawn in, often entertained and sometimes amazed. I have a hard time defining this, but I know it when it see it and I’m curious about it.

You know the line from Mao II, the DeLillo novel, “the uninventable poetry, inside the pain, of what people say”? He calls the poetry uninventable and then follows this line with heartrending snippets of dialogue—things the character’s parents used to say—that DeLillo, presumably, invented.

Because we know language as spoken before we know it as written, there might be something of homecoming or nostalgia, or in any case a deep old pleasure, whenever a novelist gets to break the narration and listen to the characters speak. Of course, dialogue is not speech. Like everything else in a novel, it’s artifice, in this case made to give an impression of speech. So, as naïvely recorded as the speech may sound, it’s still constructed. A blank wall in a room looks simple, plain, natural. But plaster and lath, or sheetrock, have been fixed to a framing which has itself been fixed to other framing which has been fixed to weight-bearing beams, and the whole thing has been sanded, primed, and painted to allow this simplicity and clarity to surround us in a room.

Does it matter that it was art that produced this feeling of artless nature? I suspect it does matter, but the habit of conflating “artful” with “false,” or calling what a craftsman does a “trick” because it produces an effect that doesn’t spring naturally from raw material, arises from the misanthropic conviction that everything in the universe is natural but us, and what we do. Which is a crumby way to live.

I sit with a notebook close by, on the subway, in a bar, at a coffee shop, at an airport, and listen to what people say. Both the parts that come out of them as if thoughtlessly and also bits of ego, performance, manipulation: all of it is part of the music of speech, the uninventable poetry that is nevertheless invented. If I use what I hear, I inevitably end up changing it, for reasons having to do with the register of the language in the rest of the book, or with the character’s own register. I rarely have any sense of who a character is until I can hear her talking on the page.

Dialogue is an expression of speech rendered on the page, then picked back up by the reader and rendered into a kind of voice speaking in her mind. There are so many elements of style in all this. Naturalism is a style, as we are always forgetting.

For me, choices in dialogue come down to looking around for what gives me pleasure. One of my piano teachers said that you need to learn the pleasure of what you’re playing. Once your body knows how to be pleased, it will return to that pleasure effortlessly.

Any thoughts on writing the second novel in the context of writing the first? A friend of mine says that the process of writing a novel always teaches her something. What did you learn from writing The End that you applied or somehow translated into this novel?

Gosh. Maybe that you can put all you think you have into a novel, and finish it, and send it out in the world, and then leave it all behind you. Emerson: “Speak what you think today in hard words and tomorrow speak what tomorrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said today.”

For the writer, every new novel begins with a bankruptcy proceeding. You have nothing left of the previous work, but all its debts have been cleared, too. You are naked, unestablished, unentitled, alone, broke, defenseless, and free as the day you were born.

Care to share a few words about your next project?

Another time, another place.