Via author's website

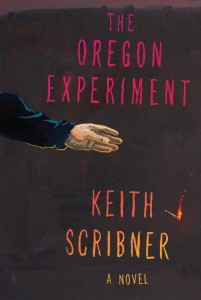

One of the things I like most about Keith Scribner’s new novel, The Oregon Experiment, is that it gets the weather right. It’s true that western Oregon is often as rainy and overcast as it is rendered, but stories set here largely ignore our bright, hot summers, the shocking color and gilded light in our springs and autumns. Not Scribner. “No sun like Oregon sun,” one character explains to another in the novel’s opening pages, even as thick fog—“Dickensian fog”—envelops them. “Warm honey in a deep blue sky.”

It’s an accurate description the afternoon I visit Scribner’s office in the Autzen House, a historic brick building that sits among small, well-maintained properties in the heart of Corvallis. The street is lined with trees, more varieties than I can identify—here a few maples and a towering elm, there a row of ginkgos and an apple, the spring air brisk on my bare arms when I pass through their shadows.

The neighborhood is quiet and peaceful, not the type of place you would imagine as a hub for anarchists and hooligans and secessionists, riots and terrorism and police brutality—not until you’ve read Scribner’s book. The Oregon Experiment takes place in a small college town like this one. The title comes from both a promise between a husband and wife and a radical movement for the secession of the Pacific Northwest, each resulting in its own kind of civil war, which turns streets like this one into battlegrounds. The result is a fascinating political thriller and beautifully imagined literary work, which is not an easy combination to pull off.

When I arrive at his office, Scribner greets me warmly and sets me up in a cushioned armchair, insisting on my comfort, then leaves to retrieve a glass of water for me, tea for himself. The room is on the second floor, filled with natural light, the walls white and the furniture blond. He received the space as part of a fellowship he received from the Oregon State University Center for the Humanities, which has also awarded him a stipend to provide a short release from teaching, allowing him to finish The Oregon Experiment and continue work on his next novel. Above his computer he has tacked a panel-work of his daughter’s watercolors, their designs abstract and dominated by red. Beside the armchair, leaning against the wall, is a bulletin board covered with scraps of paper, and a thrill runs through me when I realize they describe the scenes of the novel I’m holding.

When I arrive at his office, Scribner greets me warmly and sets me up in a cushioned armchair, insisting on my comfort, then leaves to retrieve a glass of water for me, tea for himself. The room is on the second floor, filled with natural light, the walls white and the furniture blond. He received the space as part of a fellowship he received from the Oregon State University Center for the Humanities, which has also awarded him a stipend to provide a short release from teaching, allowing him to finish The Oregon Experiment and continue work on his next novel. Above his computer he has tacked a panel-work of his daughter’s watercolors, their designs abstract and dominated by red. Beside the armchair, leaning against the wall, is a bulletin board covered with scraps of paper, and a thrill runs through me when I realize they describe the scenes of the novel I’m holding.

When Scribner returns, I ask him about the bulletin board, and he explains the process of organizing multiple perspectives and dozens of scenes, intriguing stuff for someone like me, groping through my own novel’s first draft. His manner is warm and easy, and several minutes pass before I remember my responsibility to all of you.

Interview:

J.T. Bushnell: Your third novel, The Oregon Experiment, is in bookstores, but I’d like to start at the beginning of your career. How did you get started as a writer?

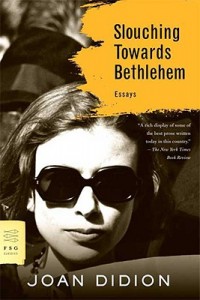

Keith Scribner: I was an economics major in college, and I had no thought of becoming a writer. I was going to do something like go to law school, or work for an investment bank. My senior year I took an expository writing class—what we’d now call a creative nonfiction class—and it was almost exclusively Joan Didion who got me excited about writing. I read “Goodbye to All That,” “On Self-Respect,” “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” “On Going Home,” “On the Morning after the Sixties,” The White Album. I had never read anything like it. I didn’t even know it was something people did in writing—writing that, to quote John Gardner, helps us know what we believe and leads us to feel uneasy about our faults and limitations. That was an enterprise I wanted to be part of.

Keith Scribner: I was an economics major in college, and I had no thought of becoming a writer. I was going to do something like go to law school, or work for an investment bank. My senior year I took an expository writing class—what we’d now call a creative nonfiction class—and it was almost exclusively Joan Didion who got me excited about writing. I read “Goodbye to All That,” “On Self-Respect,” “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” “On Going Home,” “On the Morning after the Sixties,” The White Album. I had never read anything like it. I didn’t even know it was something people did in writing—writing that, to quote John Gardner, helps us know what we believe and leads us to feel uneasy about our faults and limitations. That was an enterprise I wanted to be part of.

I had a similar career path. I thought I was going to be a reporter, so I never took any creative writing classes in college. For me there was a lot of conflict in the decision to pursue something as impossible as writing fiction seemed. Did you experience some level of conflict?

I was pretty sure it was what I wanted to do, and I didn’t question why. I questioned it later. [Laughter.] I questioned it after five years, when I was hanging sheetrock, and after seven years, when I was cutting grass. But at the time, no. I had a twenty-two-year-old’s confidence—the feeling that life was just beginning, the sense when college ended that I could step into whatever I wanted to do. And also, honestly, a kind of naiveté about how difficult it was. I’d read Hemingway’s stuff about “it’s the hardest thing I know,” and I would repeat those things, but it felt like, “Yeah, okay, it’s hard, but if I keep at it, it will work out.” Which of course is true. If you give up, you’re never going to know if it could have worked out. It’s rare to find someone, in my experience, who’s been writing every day for twenty-five years, or even ten, and hasn’t had some success.

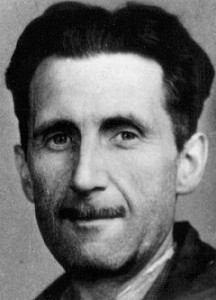

Also, I wanted to add—I got so caught up in Didion—the other essays in that class that I found inspiring were George Orwell’s “Marrakech” and “Shooting an Elephant,” E.B. White’s “Death of a Pig.” Those were all essays that completely consumed me.

White

Orwell

And yet you decided to write fiction. Was that because of your personal proclivities, or because nonfiction as a form didn’t have the foothold it does now?

Probably both. And my wonderful teacher, Karen Robertson, was really encouraging me to try fiction. Then I went to Japan after college to teach English, and I was reading fiction there, and reading Hemingway, who did his journalism and then wrote his fiction, and I thought maybe I’d do that. But, ultimately, fiction felt like the form in which I could do the most. I felt like it gave me the most freedom. And the novel always seemed a place where I could be comfortable, compared to short stories. Most fiction writers start with short stories, and I think there are a lot of short-story writers who feel like they’ve got to write a novel because of publishing demands. But for me, the larger canvas of the novel, those more extended stories and narrative arcs, that wide open space, that’s where my imagination is most inspired. Writing short stories, for me, can feel a little constraining.

You do have a few stories out there. You’ve been published in TriQuarterly, The North Atlantic Review, American Short Fiction, Quarterly West. Do you see the two forms drawing writers of different sensibilities, for the same reason poetry might draw a certain type of writer and prose another?

I do think that’s certainly the case with poetry. With my most recent story, “Paradise in a Cup,” I happened to have an idea and some material that really worked for a story. It was about a conflict, a situation, a fear, a recognition that I didn’t need fifty or sixty scenes to evoke. The idea that you have—the creative impulse and the creative spark—often screams out for a particular form, and my ideas about conflict and character and motivation tend to demand a longer form. I need the space.

You wrote two unpublished novels before you finally sold your third, The GoodLife. Through those years, how did you keep the faith and continue on and avoid feeling discouraged even though things weren’t working out immediately?

A lot of things helped me. One was that I knew how to work as a carpenter, and I was able to make an okay living doing that. I also got sick of being a carpenter. I would either injure myself or get sick of it. [Laughter.] Then I would go abroad to teach for a time, as I did in Japan and Turkey and France. I wasn’t married. I didn’t have children. I was in no hurry to settle down, buy a house, any of those things. Grace Paley advises writers to keep overhead low and surround yourself with people who believe in what you do. I think I did that. I had friends who had some level of respect for what I was pursuing, and I always kept overhead very low. I had apartments and things, but I also often lived out of a car or a backpack. I was reading constantly, and also reading interviews, being inspired by other writers, going to readings, finding a literary community. Grad school came at a good time. I was out writing on my own for four years, and then after grad school I was writing on my own a little more, and then I got the Stegner Fellowship, and obviously that was a tremendous boost. If I had doubts leading up to that, then for at least a few months those doubts were squashed, because I felt like the world had yet again told me, “You’re not completely out of your mind.” It was just after the Stegner Fellowship ended that I sold The GoodLife.

What was it about that project that made it successful in a way the others weren’t?

I think it was just better. I’m so glad I didn’t have those first two novels published. I haven’t looked at them in years and years, but I’m sure they just weren’t good enough yet. I wasn’t good enough yet.

And what allowed you to progress past that, to go from writing two novels you’re glad are locked away somewhere to writing this novel that receives critical acclaim?

It’s hard to say what allowed it, except that, as you know, the longer you write, the better you get. In every single way. The characters were probably sharper, and more compelling, and more clearly defined. The plot I’m sure was more satisfying and surprising. The structure was probably more solid. The first two novels had more innovative and complicated structures, which in my case might have been a tactic to distract the reader from weak writing. In fact, I had very different ideas about structure for The GoodLife when I got to Stanford, and it was John L’Heureux, one of my teachers, who really hit me over the head with a hammer and said, “You cannot use this structure. You’ve just got to tell the thing straight.” And I was older, I was more mature, I had read more, so I had more models to draw from. But finally, it comes down to time spent writing pages.

The GoodLife is about a kidnapping, the skeleton of which you took from a real-life news story. You follow the characters through the enactment of the crime and all the ways it goes awry, and many of the themes that emerge are social critiques and commentary about materialism and the way it drives American society. Many of the same themes emerge in your other novels, Miracle Girl and now The Oregon Experiment. What is it about this subject matter that keeps drawing you back?

I’m not the first writer to say that we all keep writing the same novel over and over. My novels are pretty different from each other; however, early on, certain thematic things grab hold of us. I think you explore them and develop them and see them through the characters in one novel, and then you start another novel, and you’re sitting there writing morning after morning, for months and years, and living with these characters, which are of course creations of ourselves, and then suddenly, through the characters, these themes—surprise, surprise—here they are again. I don’t think we exhaust certain interests. Most writers do end up returning to familiar territory, and I don’t think that’s something to worry about or apologize for.

I agree. It sounds like what you’re saying is that you keep discovering the same obsession as it emerges from each story.

Yes. Exactly.

Do you have any ideas about why this obsession keeps recurring?

It’s surely my own childhood, and my examination of my history, and the weird, uncomfortable, shifting place our family occupied in terms of social class, the place where we precariously stood. My experience with education, with friends, with living in gritty cities like Troy, New York, where Miracle Girl is set—I call it Hudson City in the novel—and out in the country in New England, and going to a fancy college. All of those experiences formed me, formed my interests, my fears, dreams, doubts. The simplest answer is that I’m still hashing those things out.

So even though you’ve pursued fiction, you’re investigating some of the same elements you might have investigated if you’d decided to write nonfiction.

Absolutely. And boy, I don’t know about you, but I don’t know any fiction writers who would claim otherwise.

I’d like to ask a little more about The Oregon Experiment. The circumstances of this novel are very provocative. You have a modern secessionist movement in the Pacific Northwest. The people you have as figureheads for the movement are a free-spirited neo-hippie and a young anarchist who might be a real political player and might simply be a hooligan. You have these wonderfully interesting professions for the two main characters—one, Naomi, is a professional nose, a scent designer, and the other, Scanlon, is a professor of mass movements and radical action. Where did these ideas come from?

The novel started for me even before I came to Oregon, when I was living in Palo Alto. It was during the WTO demonstrations in Seattle, and we had just had our first child. Seattle was a place I’d lived, and it felt very familiar. It didn’t seem far off. It wasn’t like watching demonstrations in, say, Egypt. So here I am, a new father, and I think of a character who in some ways is drawn toward the safety and security that parents want for their kids, and at the same time is sort of radicalized. And what was interesting about those demonstrations was that the plumbers, these union pipe-fitters, were walking arm-in-arm with the lesbian avengers, and teachers, and anarchists who weren’t there to break windows, and secessionists. It seemed to be a meeting of a lot of different subcultures that typically would not have any overlap at all. So I was inspired by that collision of subcultures, and I thought of a character who supports the demonstrators but might not think they were so cool if they were on his own street while his baby was sleeping in the crib.

Secessionism made sense to me for a lot of reasons, but one is that the novel, I hope, is successful at merging the political, social, and personal. All of the characters are separating themselves from something or someone, and that separation ended up working on all three levels.

As for Naomi as a nose, I came on that late. She was actually a completely different character for a long time. The novel is pretty sensuous, and smell is our most primal sense. When I came to Oregon, I was so aware of the wonderful smells here. I wanted Naomi to be someone who could help bring out an evocative connection to the place and to our primal instincts.

I especially love Naomi’s career, because it allows you an angle on the world that is, like you mentioned, very sensuous. It’s interesting to experience the world from the point of view of someone who experiences the world as smells. I’d like to ask where the real ends and the imagined begins in all this, but that doesn’t seem like a fair question for a fiction writer, so what I’ll ask instead is what sort of research you did for the novel.

Like most fiction writers, I start with Google. [Laughter.] Oddly enough, if you Google “anarchy” or “secession,” more than a few sites pop up. I read books. I met with some anarchists here, local anarchists, and talked to them about their stories, how they think, what different levels of anarchists there are, the broad definition of “anarchist” among anarchists. Some of them have some pretty organizational interests. They’re actually more anti–U.S. government than they are anarchist. They have some similarities with the secessionists in that they think the major problem is that the U.S. and its government are just too big.

The smell research was really fun. Again, I did a lot of reading. I also met with Yosh Han in San Francisco. She designs perfumes using natural essences—most of the stuff now is synthetic—and I spent a whole day with her actually creating the perfume that Naomi makes in the book. I don’t think I’m giving away too much by saying Naomi gets a new base note, which is the often unpleasant-smelling bottom note of a perfume, like musk, and she gets it from the gland of a Northwest frog. And so Yosh Han sets up her organ—hundreds of essences—and we created that base note from mosses and roots and mushrooms, a mixture of real Northwest essences. That was amazing.

So there are actually some very ugly scents in perfume?

Oh, yeah. Always the base note. Musk, you know, is a very . . . [gesturing at groin]. It’s funky stuff. Civet cat—it’s kind of like what cats spray.

My goodness. There’s got to be some metaphor here about writing.

Right? [Laughter.] Ambergris, which I mention in the book, is whale regurgitation that’s been floating on the ocean surface and baking in the sun for ten years. There’s your metaphor about writing. Patchouli is one of the more pleasant base notes, and a lot of people don’t like that by itself, but patchouli is in a lot of perfumes. You wouldn’t recognize it in the perfume, though. An average nose wouldn’t.

I suspect that one of the primary reasons this book takes place in Oregon is because you live in Oregon, but it also seems that this book has to take place in Oregon. Is that true, and if it is, why? More generally, how crucial is place to the narrative?

I think that in the popular American imagination, Oregon has always had a special place. We’re a little bit libertarian, sort of way right and way left at the same time, and I don’t mean we have right-wing people and left-wing people but that a lot of Oregon attitudes actually contain both, in a way that they don’t on the East Coast. There’s a tolerance and open-mindedness here that allow for some of the things that have become Oregon types, a kind of free-spiritedness and easiness that foster many of the social attitudes I wanted to explore.

And the story had to take place far from New York and Washington. This story couldn’t happen in Delaware. It’s not remote enough. The story in some ways operates on the colonial model, where the educated Northeast elite come out to the provinces, and they take. Just to imagine a town where these things could happen—it’s pretty damn plausible in Oregon. It’s not plausible back east, even in, say, Northampton, Massachusetts, where I’ve lived and is probably the most plausible place in all of Massachusetts for something like this to happen. In fully unified fiction, characters arise out of place, and this is the place that would produce these characters.

So you’re five novels deep. Your third novel has just been published. Does it get any easier? Or is the old saying true, that you don’t learn how to write, you just learn how to write each book?

It doesn’t get any easier. The fact that this one took me seven years, longer than any of the others, is perhaps testament to that. And I discovered something else with this one. In The GoodLife and Miracle Girl, the point-of-view characters are insiders in the places they live, places I knew something about, although I had to do a lot of research to feel that I got it right. The Oregon Experiment was originally in Scanlon’s point of view exclusively—it wasn’t until a few years into it that I expanded to multiple points of view—and I had thought that writing from Scanlon’s point of view as an outsider, I wouldn’t have to fully understand the place. I could understand Oregon as someone like myself, an outsider who comes from the East Coast. And I quickly discovered that wasn’t true, that even though Scanlon’s perceptions would often be skewed, wrong, naïve, and miss the point of the place, as the author and creator of all this, I had to understand the place, the culture of the place, the many subcultures of the place, its history, as fully as any insider.

Even if Scanlon’s wrong or naïve about something, you have to know how he’s wrong and naïve.

Yeah. Which is one of the things I’m always telling students. When I ask, “Well, how old is this character in your story?” and they say, “I don’t really know, twenty-five or thirty,” it’s not good enough. You need to know. It’s a simple little factual detail, but it’s something you need to know.

What other advice would you give to emerging writers?

Certainly write every day. Even those days when you don’t feel like writing. Perhaps those are the most important days to write. I defy anyone to actually sit there and type words and tell me that at the end of two hours you don’t have one sentence worth keeping. I think you always do. And read, read, read. You can’t refill your own creative source without reading, without reading challenging stuff, perhaps pushing the boundaries of the kind of fiction or the kind of literature in general that you’re interested in. And again, to repeat Grace Paley’s advice, keep your overhead low and surround yourself with people who believe in you. Believe in yourself. And believe that the pursuit of literature, the pursuit of art, is a great way to live a life. There are certainly things you give up for that life, but you get a lot more back.

Certainly write every day. Even those days when you don’t feel like writing. Perhaps those are the most important days to write. I defy anyone to actually sit there and type words and tell me that at the end of two hours you don’t have one sentence worth keeping. I think you always do. And read, read, read. You can’t refill your own creative source without reading, without reading challenging stuff, perhaps pushing the boundaries of the kind of fiction or the kind of literature in general that you’re interested in. And again, to repeat Grace Paley’s advice, keep your overhead low and surround yourself with people who believe in you. Believe in yourself. And believe that the pursuit of literature, the pursuit of art, is a great way to live a life. There are certainly things you give up for that life, but you get a lot more back.