As a born and raised Brooklyn girl, I can’t help but marvel at how precisely Jacob Appel manages to capture my hometown in his latest novel, The Biology of Luck (Elephant Rock, 2013). New York becomes more than just an open palm across which the characters walk (and, in this case, bicycle). Its rich history and its cultural touchstones exist not only as setting but as leading characters. As I learned more about Appel, this made sense. He’s a licensed New York City tour guide, a test that at one time, he says, was harder to pass than the BAR and MCAT combined. He’s passed those too, by the way; after earning degrees from Harvard and Columbia, Appel went on to earn degrees in history, philosophy, psychiatry, and creative writing. He’s won the Kurt Vonnegut Prize, the Walker Percy Prize, the Tobias Wolff Award, the William Faulkner-William Wisdom Creative Writing Competition, along with dozens of others. He simultaneously works as a doctor, teacher, and writer, and has sold eleven books in the past thirteen months with various indie publishers. While marketing Biology, I began calling Jacob Appel “something of a modern day Renaissance man,” because really, there’s no easy way to summarize what this guy is all about.

The first I heard of Jacob Appel was when Jotham Burrello, publisher at Elephant Rock Books, called me up one Saturday morning and left a slightly breathless, rambling message, the point of which was, “I think we found it.” It was the new book we would publish. For a small, independent, humbly-financed press, each individual project must be worth the time, effort, money, and overall passion poured into it. I must believe in a book to push it towards publication at Elephant Rock Books. After reading just the first fifty pages of The Biology of Luck, I not only believed in it, I wondered, Why hasn’t this book been published before?

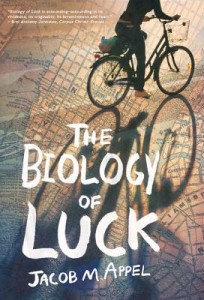

Set within a single New York City day, Biology follows the darkly humored trials and hopes of Larry Bloom, a middle-aged Jewish New York City tour guide, who, despite his lack of good looks and self-confidence, strives to be the hero of his own tale. He does not believe he will be the next great author and he is doubtful that he has what it takes to win any hearts; yet he has written the book and he clings to the hope that at the end of the day he’ll get the girl. He is, as Appel writes, his own worst enemy.

Larry’s deeply harbored love for Starshine Hart, a whimsical twenty-something, is about to come to a head. On the day in which the novel takes place, Larry is to meet Starshine for dinner and plans to reveal the book he’s written about her, also titled The Biology of Luck. During dinner he’ll open a letter that will determine whether his novel will be published. But first he must survive the day, which involves navigating a group of Dutch tourists through the city, a riot weaponized by bagels, one murder, some brief contemplation of suicide, heroism, and pre-determined fortune, one fanatical journalist, and an ongoing parade of obstacles that prove nothing short of entertaining and thought provoking. Appel expertly alternates chapters between Larry Bloom’s day and his novel about Starshine.

I recently sat down with Jacob Appel over cupcakes and coffee to chat about his work, his writing, and of course, The Biology of Luck.

Interview

Emily Schultze: How do you deal with self-doubt and fear of rejection when it comes to writing?

Jacob M. Appel: The trick is to submit early and often. I have 21,000 rejection letters. It’s like sitting on nails. If you sit on one nail, it hurts a lot. If you sit on 21,000 closely spaced nails, the weight is distributed evenly and you hardly notice.

You said earlier that Jotham Burrello may have been the second person to ever read The Biology of Luck, which would make me the third. Do you treat all your work in the same way? Or do you usually seek out feedback from fellow writers?

The best advice I ever got was not to take any writing advice from anyone without an invested interest in the project. So like now, if my agent says, I can sell this but I want you to change something, I can live with that. But that would be because she has a very invested interest in selling it. We had a scene in which a character finds a dead dog and disposes of it very callously. She felt that although that would be accurate for the character, the image of a dead dog would be so unsettling to many editors they just wouldn’t get that part. So we took out the moment. But that was not her gratuitous thought. I’ve learned that if you ask someone for an opinion, they will give it to you, simply because having an opinion is what they’re being solicited for, while they would never volunteer that opinion if you didn’t ask. So, except for someone who really has a stake in it, there’s no sense in listening to other people’s thoughts.

That’s interesting coming from someone who teaches writing workshops, where there’s a lot of feedback given by students who have varying levels of invested interest.

Well, I think people also use creative writing workshops in the wrong way. At least many people. And some people teach them in the wrong way. The goal is not to perfect pieces of writing. It is to use those pieces of writing submitted to develop techniques and craft skills so that later those writers can go write something worthwhile.

What’s your own writing process like? You mentioned that you like to retreat from the going-ons of the hospital and write at the nurses’ station when you have time.

I think that many writers make this one mistake, and that is to start writing too soon. Not too soon in their lives, but when writing a particular piece. They haven’t figured out what it’s about yet before they start writing it. And I know there are top writers who encourage people to do that, to brainstorm and get all their ideas down on paper. I don’t think it’s effective. I mean if that’s your natural way of writing, all the more power to you, the same way that if sitting in a small, dark room staring at an orange is your way to find inspiration, all the more power to you. But if it’s not, then I think in general it would be best to encourage people to figure out what they’re doing before they do it.

Many of the writing workshops I experienced as an undergrad put a lot of emphasis on that generative process of ideas.

Many of the writing workshops I experienced as an undergrad put a lot of emphasis on that generative process of ideas.

I am doubtful that any great works of literature began in my, or anyone else’s, workshop in that way. Writing exercises…they’re a great way for teachers to fill time, but they’re not really a great way to generate ideas. The only time they’re really helpful is when someone’s thought through the project for a long time before they’ve come to class.

How has your perception of education and its importance changed over the years?

Mark Twain said he never let his education interfere with his learning, which is a somewhat valuable thought. I think in some ways our education system is deeply skewed in the wrong direction, and as someone with nine graduate degrees, I really think we should just give everyone their degree on day one, and the people who want to stay and learn something should be allowed to. That’s not my original idea. Someone suggested it years ago in the New York Times and it really resonated with me. I think there’s far too much emphasis on testing and practical skills. And what’s struck me is that, often, the people who, for the most part, don’t find long-term careers are not those who study English Literature or the History of Art. They’re those who study these quasi-intellectual exercises that really are about the middle echelons of the business world. Nobody should go to college and earn a degree in Human Resource Management, or Inter-Business Communication, or whatever these meaningless degrees are. Because these people don’t learn any useful skills. They learn very confined, task oriented skills that are hard to adapt. They’re much less enjoyable experiences. Reading Shakespeare is a fulfilling experience for many people. Reading corporation human resource code has a much smaller appeal. And they don’t teach people to think in a broader way. They teach people to think in a narrower way. They teach people that education is a tool rather than an element of fulfillment.

Where in the timeline of your nine degrees did your creative writing MFA come in?

I earned the writing degree halfway through law school. It was never my original intention, but any sane person who has spent a year in law school has a moment where they seriously consider doing something else. I’m glad I did it, by the way.

You recently stated that realism is different from reality. There is, of course, the ongoing debate of what it means to label something as nonfiction. What are your thoughts on that?

I think it’s important to remember that literally speaking, there is no such thing as truth. When you write something, you’re choosing to emphasize certain things and underplay others. You’re presenting your subjective take on what happened and what didn’t. It becomes your personal truth. The goal of nonfiction is to get the overall spirit of the story across, to make the over-arching point, the emotional connection. If you alter the details that are incidental in that way, to further that over-arching point, I think that’s fine. I don’t think you can do what James Frey did and marginally alter the story to make a larger point, to where it transforms that point so it’s no longer reality. But a really good account of this is how I have a number of essays that I’ve written about patients. Now, obviously I can’t write about them, even with their permission these days. So some minor details of my essays have been changed to protect the identities of those involved. That means that if one of the patients was a middle-aged engineer, I’d make him a middle-aged lawyer. But that has no bearing on his suffering from his brain tumor.

Let’s talk more about The Biology of Luck. You’ve said that before you began writing it, you had a pretty good idea of all the characters and the plot. Was the single day structure what you had always intended for it?

Yeah, absolutely. And that’s because part of the original conception for the book came from Ulysses, which is set in one day.

When you’re getting ready to write a story, do you find that you’re often first inspired by the place and its effect, or do you kind of fit the place around the characters that you develop?

When you’re getting ready to write a story, do you find that you’re often first inspired by the place and its effect, or do you kind of fit the place around the characters that you develop?

I rarely ever start with place because almost all of my stories start conceptually, with an idea. So the idea may be that I’m going to write the modern day Ulysses about a tour guide and have it be a novel within a novel, or like my first novel, I’m going to write a story about a man who refuses to stand up during the national anthem at a baseball game and is branded a terrorist as a result. But as soon as I make that large, conceptual decision, then I have to choose a place. Because everything else follows that decision. How these characters will sound, how they’ll move in the world…you know, people in Chicago sound differently than people in New York. I think unfortunately, we writers pay much less attention to how people speak than we should.

You mean like how dialect is represented in text?

I actually think writers often try to capture dialect. But it’s the diction and syntax, whether we say lightning bug or firefly, whether you carry a pail or a bucket to the beach, whether you close blinds or shades. People do speak very distinctively. Readers might not rationally or consciously recognize that in fiction, but on a subconscious level they know whether the people sound right or sound wrong. It’s sort of what we mean when we say somebody’s a good reader. It means that they can pick that up intuitively.

Could Biology take place anywhere but New York?

No. In my psychotic moments I thought maybe I’d put it in Dublin, but then I always came to my senses. There were moments when I thought maybe the whole thing would take place only in Manhattan. But then I decided to expand it into the five boroughs.

Between indie publishers and bigger houses, marketing options are obviously very different processes. On one hand there’s the built in collaboration that comes from working with a small press like Elephant Rock, and on the other hand there’s the rolodex of contacts and resources that allow bigger houses to have your book on display at Barnes and Nobles within the week it’s released, though writers may not have as much input in these larger houses. So what are the ideal marketing options for you?

I think the vast majority of people who publish with large house publishers do not end up on the front table at Barnes and Nobles, do not end up in airports; they end up with their books being utterly buried and forgotten very, very quickly. The advantage of a good independent publisher is that they’re very invested in the project. They’re not going to decide, you know, we didn’t like your book very much after all. I know many people who have published books in very fancy places and gotten good lump sums of money, and they’ve sold no books. The other thing I’ve learned is that there are few industries that know less about what they do and less about their product than large publishers. Coca-Cola knows exactly who buys all of its soda, and they market their soda accordingly. Publishing cares very much about marketing, yet they have no idea who buys their books.

In Biology, you have this dark way of saying things, of bringing up larger issues in an under-the-table way that proves very entertaining. Do you think it’s a writer’s responsibility to extend fiction to these greater realities, to attempt to broaden the reader’s train of thought beyond the narrative?

When you’re writing a novel, you sort of give yourself pause. I am not really transforming Western civilization, and there are things in the world that really matter, like the people being brutalized under the dictatorship of Teodoro Obiang in Equatorial Guinea, and my novel is not going to stop that. So, in the limited venues you have to point out these things to people, you should try and assert that surreptitiously however you can, so that it will occasionally pop into peoples mind before they go back to drinking orange juice and reading my book.

So you’re referring to a responsibility that writers have, that if you have the ability to write and form a story, you should try and bring forth these ideas that relate to the bigger picture of the world we live in?

Absolutely. And I think what’s unfortunate is that when writers do that, they tend to focus on very large, high profile issues. There are a lot of writers out there talking about typhoon victims, or earthquake victims, or other horrific tragedies, and certainly those people have suffered greatly. But the more systematic, pervasive horrors of the world go unnoticed because they occur every day.

As a writer with over 200 publications, how do you feel you fit into the evolving publishing world?

Well, the first thing I should say is that I’m still way below the radar screen. The only solace I take is that if I went out to a restaurant for dinner, and Alice Munro went to the same restaurant for dinner, nobody would recognize either of us. The point being that there really is no such thing as celebrity writers in the way there once was. No matter how successful you are as a writer, you’re still a writer. And I think the really sad thing is not that there are a lot of people out there in creative writing workshops dreaming of publishing their novel or short story collection and can’t do it. Because if they persevere, a lot of those people will do it. It’s the delusion that many of those students have that when they publish their novel, suddenly their life is going to change and society is going to come to a grinding halt to honor them. The reality is that is not the case. And it’s not just not the case if you publish with small independent publishers, it’s not the case if you publish on the front line of bigger publishers too. You’re still just a relatively obscure person and a cog in the machine.

I’ll never forget when we first met and I told you we’d have to plan a release party for The Biology of Luck, your immediate reaction was “I hate parties.” Do you still hate parties?

Even more so. I’m doing the best I can. I was telling [my friend] Rosalie by email this morning that if I could have my ideal weekend I would do nothing but go home to my apartment and stare at the wall. Just stare and let my mind wander.