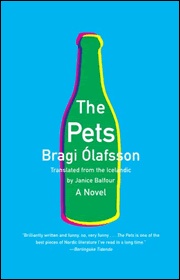

Herman Melville wrote, in his magnum opus, Moby Dick, that “there is no place like a bed for confidential disclosures between friends.” This is an apt starting point in any discussion of Bragi Ólafsson’s The Pets. In the book, Ólafsson’s young Icelandic protagonist spends the majority of the narrative voyeuristically peeking out from under his bed, under the overhanging sheets, watching friends, acquaintances, and a love interest, as if he were at a zoo.

Herman Melville wrote, in his magnum opus, Moby Dick, that “there is no place like a bed for confidential disclosures between friends.” This is an apt starting point in any discussion of Bragi Ólafsson’s The Pets. In the book, Ólafsson’s young Icelandic protagonist spends the majority of the narrative voyeuristically peeking out from under his bed, under the overhanging sheets, watching friends, acquaintances, and a love interest, as if he were at a zoo.

Eminently readable, The Pets disguises some really interesting sociological questions in a clean, conversational prose style that is, at first glance, deceptively simple. Arriving home from a trip abroad, Emil puts on some water for tea, makes a phone call, and begins to relax. Then he hears a knock at the door.

With an accompanying feeling of revulsion, he realizes that the person seeking admittance is actually an acquaintance from his past, someone who is supposed to be in a Swedish mental institution. Retreating to a rear bedroom to give the impression that no one is around, he watches in horror as Havard, the intruder, climbs in through a window and makes himself at home. To escape detection, Emil crawls under the bed, remaining in the confined space for the duration of the book.

In the simpler opening passages of the novel, the reader may be tempted to believe that the narrative has been designed to explore the defective Havard. He does, after all, read through Emil’s email, crack into the supply of duty-free liquor that he finds in the kitchen, and masturbate into the bathroom sink, and, watching and listening to everything, Emil is appropriately horrified. But something peculiar happens about half way through the book. The story becomes equally about Emil and his own musings (still from under the bed) about the relationships he has allowed himself to participate in.

Even as he wonders “why the hell one ever wants to get to know other people, or let them take advantage of oneself,” and determines that “one shouldn’t let others into one’s life,” the reader realizes that the menagerie of Ólafsson’s characters are Emil’s pets, and very much like real pets, once let into his life, he is responsible for them in perpetuity.

Convinced that Emil has just “nipped out,” and will soon reappear, Havard fields several phone calls, inviting each of the callers to the apartment. Emil’s random assortment of radically different friends, acquaintances, and his new love interest find themselves thrown together in an awkward social situation, where each has to adapt to the others while waiting for his supposed return. One by one, Emil’s “pets” arrive, and the narrative grows increasingly complicated. Emil, all the while, examines his relationship with each of the visitors, listening to their voices from the back bedroom even while sifting through his own memories of the past. Through an analogous incident that is so bizarre, one can’t help but feel it’s been drawn from life, the reader finds that relationships, like pets, must be both actively managed and nurtured to remain healthy. If not properly cared for, relationships will petrify and end. It is, in fact, Emil’s inability to take an active role in the goings on at his apartment that keeps him confined to the bedroom, and more significantly keeps him from satisfying his interest in the alluring and socially adept Greta, who seems to hold her own in his living room.

As the story reaches its crescendo, Ólafsson all but overtly acknowledges a literary debt to Melville by citing a passage from Moby Dick that might easily have been the kernel from which The Pets has grown. It is a passage that comes to Emil while he bides his time beneath the bed, and seems, in fact, to encapsulate his entire horrific experience in the novel. “Not ignoring what is good,” he remembers,

“I am quick to perceive a horror, and could still be social with it—would they let me—since it is but well to be on friendly terms with all the inmates of the place one lodges in.”

Melville allusions surface again and again in the book, as do countless music references that a reader with less antiquated tastes than myself will certainly appreciate. One can’t help, in fact, but to feel as if Ólafsson is stylistically channeling Nick Hornby to some extent. Emil’s personable literary voice, complete with self-abasing modesty and compelling honesty, seasoned mildly with wit, would still be enjoyable were the book twice as long.