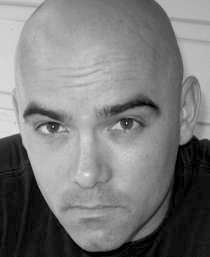

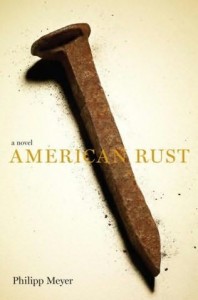

American Rust is a novel of aftermath. It is a novel not of the American dream, not of the green light at the end of the dock, but a novel in which dreams have derailed. Here, in the debut of one of the The New Yorker’s 20 Under 40 authors, the essence of Buell, Pennsylvania is rust: retired warehouses, rattling railways, prisons, Wal-Mart –– the industrial underpinnings of America the cause of all this quiet catastrophe.

American Rust is a novel of aftermath. It is a novel not of the American dream, not of the green light at the end of the dock, but a novel in which dreams have derailed. Here, in the debut of one of the The New Yorker’s 20 Under 40 authors, the essence of Buell, Pennsylvania is rust: retired warehouses, rattling railways, prisons, Wal-Mart –– the industrial underpinnings of America the cause of all this quiet catastrophe.

Philipp Meyer’s novel opens sharply with an early hook, a homicide triggered by failed jock, Billy Poe, though committed by quiet intellectual Isaac English. Despite their mutual responsibility for the murder, they are not sympathetic culprits. At one time, each of the men embodied the hopes of their decaying steel town: Isaac could have gone to Yale, and Poe aspired to football stardom at Colgate College. Despite much-emphasized class differences, their friendship is a firm one; when Isaac skips town, Poe prepares to take the full fall.

Although the story begins with Isaac and Poe, the novel spirals early on into multiple points-of-view: six, all told. It moves in short, sometimes staccato, bursts from Poe’s mother to the town sheriff to Isaac’s sister, the pace and shift in perspectives mimicking the murder’s epidemic effect. In rapid succession, Isaac becomes a runaway delinquent, Poe’s mother kicks her husband out, and the town sheriff tampers with the evidence. Everyone, it seems, starts out short; the entire town and novel sit upon on a shared precipice.

Beneath the swift-moving plot, Meyer’s stoic prose provides a counterweight to the action. Each point-of-view is written in tight third-person, and the characters’ voices, while individual, all use the same sentence-fragment construction that creates a sense of intimacy and tension. For instance, here Grace worries about her son: “She felt sick to her stomach thinking about it. She had done this to herself, to Billy. Deep breath. Of course it wasn’t fair. Your entire life’s work, that child.” The self-instruction to take a deep breath is a quintessential Meyer sentence –– action is often folded into thought in this manner. As in Mrs. Dalloway, we have a sense that we are following every tic of Grace’s mind.

In the other (male) points-of-view, Meyer heightens this same construction by eliding punctuation in a more exaggerated manner. Take Poe’s self-remonstration: “Look at you he thought you are not thinking right you should not even be here with her.” With Isaac, bum genius, Meyer keeps the structure but complicates the texture with unusual verbs and hints of Isaac’s abstract erudition:

Sleeping or awake, no difference. Gray area between them. Dull blue light from the porthole and the view of the car behind you. Noise of the train, vibration, you’re a part of it, rattling. Meat tenderizing. Forgive us our daily softness.

The effect here is ultimately reminiscent of a steel-working Frank O’Hara, if he kept to five to ten-word sentences. Cormac McCarthy also comes to mind, though here the spare prose evokes fields of steel more than dry desert, and the characters seem more resigned than McCarthy’s defiants.

Topically, there’s an eerie timeliness to American Rust. “The real problem is that the average citizen does not have a job he can be good at,” a former police chief declares midway, and this aphorism steps well outside the novel into an uncomfortable, contemporary truth. And Rust Belt America, absolutely, is its own character here. Even when Isaac journeys on a railcar out to Detroit, he sees more steel works (though, he notes, more modern); he sees fried chicken shacks, laundromats that advertise their hot water. In this way, Isaac’s trip across America functions less as a plot point, and more as a way for Meyer to stretch the novel beyond the narrow world of one ghost town into many. Isaac is very much a Huckleberry Finn, watching the industrial waste float by from his railcar.

Despite American Rust’s rough-and-tumble masculinity – the murder, hunting, robberies, prison, and a notable failure of the Bechdel Test – a surprising softness prevails. As befits the book’s epic nature, there are several love affairs, all delightfully complex. Love complicates Poe especially, whose dalliance with Isaac’s brilliant sister lets him seem good enough for an intellectual, and lets her make some welcome mistakes. Furthermore, much of the plot ultimately hinges on romance: the sheriff’s old flame for Poe’s mother makes his power to hurt or help Poe a dramatic subplot. And perhaps more importantly, the romances allow for a qualified, foolish hope.

Although American Rust takes place over just a few weeks, it leaves behind a sense of half a century. There are no heroes here, and there are mistakes aplenty. But it’s pleasingly hard to place blame – the Achilles’ heel of these characters is, most of all, the misfortunes of their time and place.