The word “zettabyte” sounds nasty, doesn’t it? Brings to mind a kind of futuristic flea, or maybe an entire horde of them, a swarm of manmade nanobugs programmed to drill down through skulls to feed on the fatty brain beneath, depolarizing the way the mind thinks and perceives the world. The zettabyte. Little bugger could be downright dangerous.

The word “zettabyte” sounds nasty, doesn’t it? Brings to mind a kind of futuristic flea, or maybe an entire horde of them, a swarm of manmade nanobugs programmed to drill down through skulls to feed on the fatty brain beneath, depolarizing the way the mind thinks and perceives the world. The zettabyte. Little bugger could be downright dangerous.

But the zettabyte is a form of measurement. Equal to one billion terabytes, it will soon represent humanity’s total digital output when videos and social networking sites push us past the milestone later this year. It’s a gaudy number that looks more like binary code than anything quantifiable: 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 bytes.

That we’re talking in zettabytes at all is a testament to the Internet’s prodigious growth. With Internet traffic doubling every two years, the zettabyte will eventually become an annual rite of traffic rather than an aggregate. After all, between 2008 and 2009 alone, IP traffic in North America grew 47.9%.

During this time, Dzanc’s Best of the Web 2010 grew a nearly equivalent 50.8%. Not bad for an anthology that’s only in its third year of existence.

I don’t know what a zettabyte of literature might look like, but I applaud Kathy Fish and Matt Bell, the anthology’s Guest Editor and Series Editor, respectively, for trying to keep pace with the all-mighty Web. It can’t be easy to track—let alone read—let alone rank—all the new online journals and literary portals filling America’s zettabyte destiny, but Fish and Bell epitomize what they anthologize. Best of the Web 2010 does what you’d expect an anthology of Web-based writing to do, in that it embraces the best of the Web, the whole Web: not just short stories, but flash, flash prose, experiments in structure and surrealism—and not just fiction, but the Web’s best poems and essays, and, yes, even a book review.

Every year, I enjoy my annual installment of The Best American Short Stories for anthologizing what I expect: familiar fiction from familiar publications from familiar names. And although some of these familiar names have begun to extend into the online space, trusting their work to new digital editors and readers, I enjoy installments of Best of the Web for anthologizing the unexpected, the new: everything else, from everywhere else, from everyone else.

Best of the Web 2010 contains ninety-five works—not quite a zettabyte, but perhaps my original vision of the zettabyte: ninety-five nano-sized pieces that drilled down through my skull to feed on the fatty brain beneath, reorienting my understanding of online literature, depolarizing the way my writer mind perceives pace and structure, perspective and linearity.

Best of the Web 2010. No little bugger, but still downright dangerous.

* * *

What’s New, Isn’t

Please don’t think I’m so smart as to use Cara Barer’s incredible book art for anything but pie-chart imagery. This is no infographic statement on print versus digital; I simply thought it would look cool.

I think that’s what I like best about Best of the Web 2010: the stories are smart, but they’re also just so damn cool—collected works less concerned about molds and reputations than expanding our understanding of what literature—online or otherwise—can achieve. These stories are experimental. They’re emotional. They don’t limit themselves to a few paragraphs to be edgy or modern; don’t flirt with headers and structure to cater to the computer monitor; don’t flip points of view or reference pop culture to be ironic. They—like their poetic and essayistic counterparts—don’t cater to the Web because they operate on it. They are simply stories, unique forms of art. Narratives the only way they can be told. Fish probably said it best when she described her decision-making process in the book’s introduction: “Did this writing open my eyes? Will I remember it months from now? Was it beautiful or strange or completely fresh and new? Did this writing unravel me?”

As a fan of last year’s anthology, I have to admit I opened the 2010 edition looking for publications and writers I recognized from the year prior. I loved Michael Czyniejewski’s “On the Other Hand” in 2009 (how can one not love a story where two characters’ hands get swapped in a surgery-room mix up?) and fully expected the author’s “beautiful” and “strange” and “completely fresh and new” storytelling to satisfy Fish’s criteria here in 2010. And then there he was, in this year’s edition for “Pregnant with Peanut Butter,” in spite of the fact that his 2008 publisher, Waccamaw, who published two stories in last year’s edition, was not, along with 95% of Czyniejewski’s fellow contributors. Only five returned for the 2010 edition.

This development puzzled me. With my favorite authors and publications from the year prior—Todd Hasak-Lowy who wrote about the sadness of being a Detroit Lions fan (you’ve got nothing on my Cubs), Matt Getty’s surreal take on “fasting girls”— nowhere to be seen, I grew increasingly fascinated with the differences between the two anthologies. Not just the shift in storytelling forms, but the shift in author and publication mix. As a business school graduate without an MFA, I suppose this is how my mind works, how it conceptualizes things. Here I am, using numbers to define art. Being stupid. Shallow. But at the same time, there are trends here, as there are in nearly everything. Perhaps if I dug in analytically, I might gain an insight in how the online space was maturing and shifting.

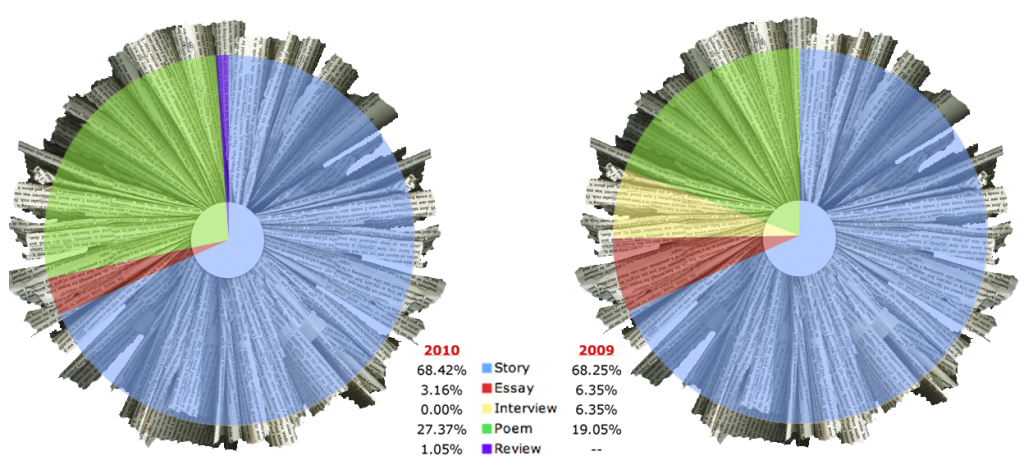

The most surprising development was this review’s first insight, viewable in the pie charts at the top of this section. While the twin pies above suggest the storytelling mix has remained constant year over year on a proportional basis, fiction composing 68% of the last two editions, this thinking doesn’t factor in scale. In reality, the 2010 anthology contains twenty-two more stories than its predecessor. While there is one less essay (and trust me, the lines are so incredibly blurry on some of these works that I wish I could have called a few authors to ask for confirmation that their prose wasn’t a prose poem, or that this thing I’m reading, dripping in authenticity, was indeed fiction and not a personal memoir) in this year’s collection, poetry saw a considerable 8% boost. 2010 is 2009 on speed—much of the same content but more of it, a DSL’d anthology versus modem’d.

The macro trend here suggests a possible migration of literary talent from print to digital. It suggests a push from sturdy stories to unraveling ones. It suggests literary magazines have established themselves online in more significant ways. It suggests authors no longer give a hoot about the stigma of online versus print. It suggests Dzanc got a good deal on paper. Or it suggests that the Web is simply growing, naturally, and for literary sites feeding the growth, there is enough readership to go around. But all these theories fail to recognize what Bell and Fish have: that a burgeoning Internet doesn’t require a burgeoning Best of the Web; rather, the burgeoning quality of these new works’ range and breadth and honesty is what demanded placement in the anthology.

Given this, and our impending zettabyte, Dzanc better send a Christmas card to the paper people after all. Things have only begun to unravel.

* * *

Who’s New, Is

Our history with print’s first-rate publications can be a comforting force, a grid of familiar local streets against the sand-swept dunes of online. With print, we know the lay of the land. Whereas, the digital landscape is ever shifting—the uninitiated could spend forty years wandering it for the Promised Land. And it’s this lack of familiarity with digital’s landscape that makes Dzanc’s anthology so incredibly necessary: for new and old writers alike, it’s a guidebook as much as it is a book-book.

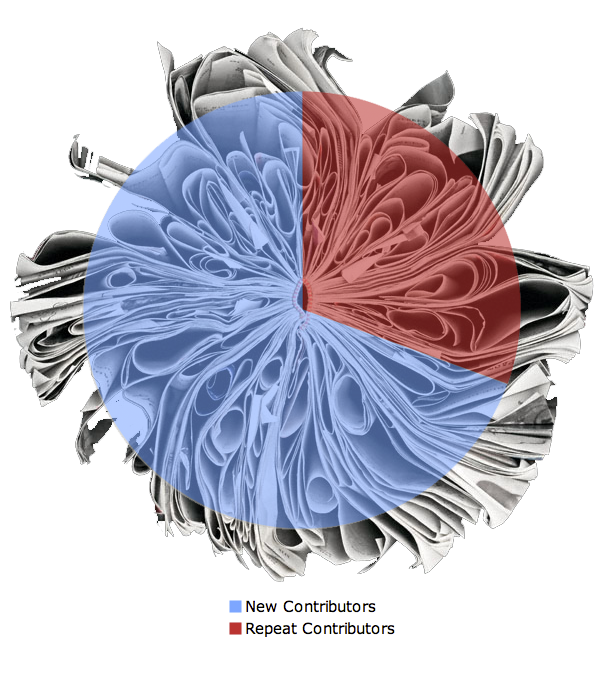

And yes, the need for a guidebook is very real. As you can see above, less than a third of the publications that contributed to the 2009 anthology provided content for this year’s. The sand hasn’t rested long enough to crown these repeat-publishers online’s main “boulevards,” but publications like Brevity, failbetter, FRiGG, Guernica, Memorious, storyGLOSSIA, and Wigleaf have all done their part to solidify the online space with their consistency. Maybe placement on library shelves is impossible, but why not in a librarian’s bookmarks? As Bell wrote in his introduction, “There is room—and perhaps even a need—for our literary community to have both print and online incarnations, and for both to thrive. We’re lucky to have as many options as we do, arguably more than any generation of readers and writers has ever had.”

Maybe most importantly, the 66.3% spike in new contributors is significant in that it gives hope to writers and editors that works are being judged on the merit of their storytelling. It’s also a percentage I like to think of as the unraveling factor. With only 5% of Best of the Web 2010 composed of returning authors, online’s wild growth and steady transformation makes it the overgrown forest to print’s manicured fairway—alive and teeming with life, a different kind of game altogether.

* * *

What Actually Matters

But for all the analytical mumbo-jumbo, one cannot forget that beyond the bylines and table of contents, here lies more than 400 pages that will punch you raw. In a story entitled “Touching the Spine,” by Charles Lennox, one brother pummels another. Again and again, he punches his brother. “I punch him four times and hear the foundation of the world crack open. I punch him forty-two times and my left hand breaks.” The beating continues until the punching brother thinks he can feel his brother’s spine. “I am the shovel and he is the dirt,” he says, and this entire story—only the eighth piece in the anthology—becomes a perfect pacesetter for how one will be affected by all the works that follow.

In fact, writing about it now, I see how the anthology progresses naturally, constructed in ways that seem more intentional than when I was first reading. The story immediately preceding Lennox’s focuses on brilliant minds incapable of simple human emotions—a group of geniuses, alone, trapped by their intellect, begin to realize the concept of love only after one amongst the clan goes against the grain to pursue it. In “The Genius Meetings,” Elizabeth Crane writes: “We secretly imagine our lives with one perfect woman who will take us away from ourselves, spirit us away on clouds and whales and the shoulders of giants, who will show us things we have never seen, and who we will stay with forever.” It’s a fitting note and touching sentiment, as the anthology itself is preparing to push off shore to show us things we ourselves have never seen.

The first of these lies directly on the other side of Lennox. Dan Chaon’s essay, “What Happened to Sheila,” is worth the purchase price of the anthology alone. Originally published in The Rumpus, it illustrates how Chaon’s wife, Sheila Schwartz, poured herself into work as cancer returned to her a final time. We voyage back to observe Dan and Sheila’s unconventional courtship and then see how their illogical, age-gapped union—though, really, what love is logical?—led, in part, to how they treated the hard truth of Sheila’s fate just as illogically. To be perfectly honest, I’m at a loss for how to properly describe the piece. There’s so much. And how can I when “loss,” the word itself, is so earnestly explored in the essay’s conclusion?

“Loss” is a good word, I think, because you spend so much time thinking that you can find them somewhere. The fact they are gone—vanished—is the most unreal thing you can imagine, and so part of you keeps searching. But there are gaps in the world, now. Places that she occupied that are just blank spots.

In the end, it is a passage like this—a hard and brutal purge—that shows how Sheila, a slightly older teacher, might have educated her husband, the younger student. The advice she gave all her students—to take their work seriously because “this is the piece of you that will last, this is you, so you’ve got to do it right”—could not ring more true than in the digital monument her husband erected to their relationship on The Rumpus, gathered here as one of the year’s Best.

This depth of searching, of meditation, found in Chaon’s essay is not what some readers expect to find online. The Internet is a place of scrolling and skimming, after all. And like Chaon, Terese Svoboda provides the anthology with yet another story that breaks this mold with a level of sophistication that no doubt required readers who first found it online to print it out, pen in hand. At least to me, “Swanbit” meant nothing until I read it a third time, unraveling and unraveling and unraveling until, finally, the last line of the story unraveled me. “The swan circles, some say, a certain spot.” I won’t ruin it for you because it’s a line I want you to not ruin for somebody else.

There are other lines I can’t forget, such as the discordance of story and structure created through the title of Emily Bromfield’s “One Way To Cook An Eel.” The title and each subsequent header give the story an eerie sense of doom. As the narrative revolves around the loneliness of a divorced, lottery-playing fishmonger, readers find themselves pinned under an ever-expanding sense of anxiety as they wonder what will happen to the eel this man adopted, the eel he loves and takes care of even as subject headers—“Step 4: Butter a saucepan, season with nutmeg, salt and pepper, and cover with lemon and onions”—describe steps on how to prepare it. How can the title of the story be reconciled against the delicate balance of their lonely lives together?

In the end, no story demanded more reconciliation than Steven J. McDermott’s “When a Furnace Is All That Remains.” After reading Best of the Web front to back, I found myself returning to this single story over and again, unsure why it was my favorite but confident the Web itself could help me unearth the answer.

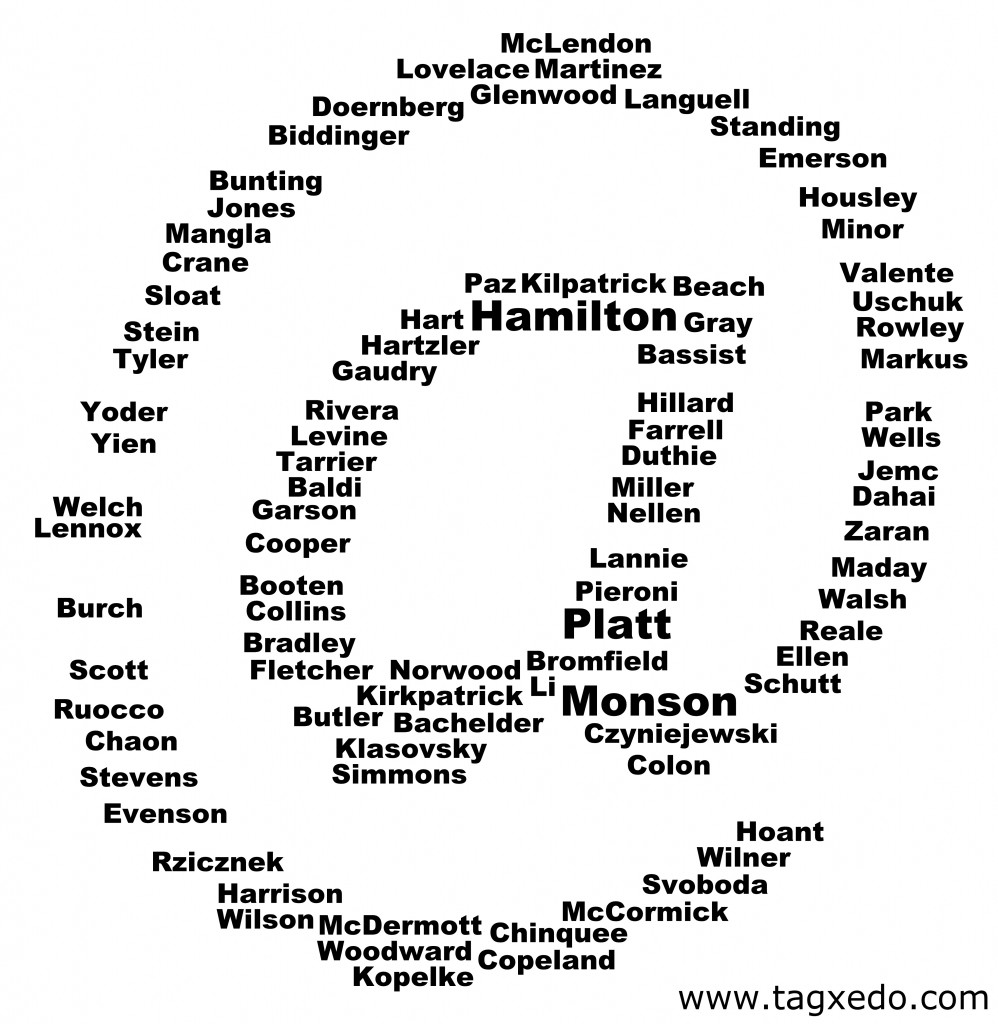

McDermott’s story is published online and therefore copy-pastable. Since the story was available digitally, I could have done just about anything: translated it into another language, posted it to a forum, plugged it into an application that would read it to me in a wise, British man’s voice. I chose to utilize the word cloud generator Tagxedo to graphically represent the story’s most commonly printed words. The resulting word cloud suggested McDermott’s story was about a regulator, furnace, matches, light, or “whump,” a sound effect. These were the words that Tagxedo claimed dominated the story about a young man trying to light a golf course’s furnace.

Using Tagxedo’s software, I customized the word cloud into four prison bars, a bit of symbolism since McDermott’s protagonist will have violated his probation if he loses his job. In going back into the story for this icon and meaning, I went beyond “word frequency” to think more deeply about the story beneath—I began interacting with it, customizing it in ways I’ve never done before. I was making it my own.

Whereas the narrative’s alternation between six segments in time and five “signs of trouble” slowly revealed why any man would care so much about lighting a furnace, the story’s gritty details gave the struggle real weight and a terrifying momentum. And as components in a word cloud, these words—“match,” “regulator,” “light”—galvanize our own feelings of guilt for the character’s luck with the furnace. As readers, we wonder if pitying his situation transfers into pitying him for the bad decision that got him here, a pharmacy robbery. Yes, we know he’s a fuck-up because he keeps fucking everything up, but something about his perseverance with the furnace endears us to him. He pisses on it. Knowing there is a risk of explosion, he lights a fire under the tank hoping to thaw its freeze. Is this desperation? Or commitment to a new life? We end up worrying whether or not he’s going to blow himself up; if his boss will arrive at the clubhouse to find the charred remains of a juvie hugging the pieces of a furnace.

All this…in three-and-a-half pages. It’s fitting that we don’t learn until the fourth section that keeping this job—contingent on keeping the furnace lit—is the one way McDermott’s protagonist gets to stay on probation. The young man never says it, but the intensity of his commitment suggests reigniting a golf club’s pilot light is the most important task of his young life. It keeps the light lit on his own freedom, a word that one won’t find in my word cloud but maybe in the white space between its bars.

* * *

Binding online stories into print provides them with access to a world they might have otherwise never known; beyond putting digital literature into brick-and-mortar bookstores, inclusion is a recognition and declaration of quality (despite understanding that any selection process is subject to aesthetics and taste). It places authors and publications onto the map by putting them into the “guidebook” as any other “best of” anthology does.

But perhaps the mission can still be embraced more fully. The addition of an actual Web element could do more than simply support the channel that produced these stories, but service it. This could be as easy a dedicated URL where readers can discuss stories and post thoughts or perceptions. Or maybe an extended version of the anthology, available online and on e-readers, can make “Notable” stories that could not be published accessible digitally.

Sure, such moves would add bits of data to our upcoming global zettabyte milestone. Word clouds, pie charts, and online reviews like this one only add as well. But when so much of the Web’s best can be anthologized in collections like Best of the Web, it seems responsible to reciprocate, to feed the Web with as much literary content as it desires. After all, if the Internet plans on doubling in traffic every other year, maybe we should start preparing for a Best of the Web that publishes bi-annually; or, more fittingly, does so digitally, installing itself beside its stories to live online in perpetuity.