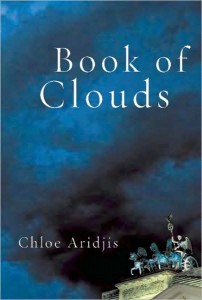

For this fiction writer, Chloe Aridjis‘s first novel, Book of Clouds (Black Cat, 2009), proved an immensely pleasurable and thought-provoking read.

For this fiction writer, Chloe Aridjis‘s first novel, Book of Clouds (Black Cat, 2009), proved an immensely pleasurable and thought-provoking read.

First: the pleasure. I was professionally trained in history, with a focus on the twentieth century in Europe. And I am a granddaughter of German Jews who fled the Nazis. A novel set in Berlin in the early part of the twenty-first century, featuring a protagonist who hails from a family that owns the largest Jewish deli in Mexico City and another character who is an elderly historian named Doktor Weiss, is likely to capture my interest. Add to that some of the edgier content (“‘Nazi, Stasi, what’s the difference?'”), and the very intelligent prose overall, and Book of Clouds is simply a satisfying read on multiple personal levels.

Chloe Ardijis / photo by Hartwig Klappert

But there’s no question that for any literary fiction writer, this novel presents quite a lot to mull over. Throughout my reading, for instance, I kept hearing the voice of one of my favorite fiction instructors: Characters must want something, and want it intensely, she’d say. Weak character motivation was a flaw in the early drafts of my own first (and still unpublished) novel, she’d pointed out. It remains, I fear, a problem in much for my fiction. So I found it puzzling that Tatiana, the main character of Book of Clouds, seems rather lacking in the drive department.

In fact, Tatiana tells us several times how, in Berlin, she has become “a professional in lost time.” It is “impossible to account for all the hours.” She spends most of her days and nights alone and finds herself “needing other people less and less.” Aside from her part-time job as a transcriber for the elderly historian, “every day weighed more or less the same.” Except for the particular “nagging pitch” of Sundays, when she is reminded that “there’s solitude and then there’s loneliness,” none of this seems to trouble her. It isn’t as though she left Mexico for Germany in the first place to pursue to some burning ambition:

At university I considered doing French but my teacher at the Institut Français killed the language for me by assigning Jacques Prévert for weeks on end and although my father kept insisting that not all French poets wrote like him I couldn’t get Prévert out of my head each time I heard the words pleurer or parole, so after a customer at the deli left behind a Stefan Zweig novella in translation, I don’t remember which, I decided to switch to German and enrolled at the Goethe Institute….To everyone’s amazement, and only slightly less to my own, I came in first in the Institute’s nationwide exam. The prize: a year in Berlin, free room and board, advanced German classes and a citywide travel pass.

Her Berlin sojourn extends past that first year. Tatiana has spent five years in the city by the time she makes the acquaintance of Jonas, a meteorologist whom she meets when her employer sends her to interview him about a drawing he had completed years earlier as a child in East Berlin. And by this point, the reader senses that Tatiana must locate some personal resonance in the explanation Jonas offers for his fascination with clouds:

And, well, you know, a whole existence might be reduced to drifting upwards to join a cloud rack, merging with the slow-moving flock and then, in a matter of minutes, without having left any imprint on the world, returning to the atmosphere the elements it had been lent.

Which leads to a related craft-oriented puzzle: Surely, I am not the only fiction writer who has been warned against attempting a novel in the voice of a first-person narrator who, to put it kindly, lacks a certain dynamism.

But as I thought about it, I realized that this novel nonetheless succeeds for at least two reasons.

First, we learn that Tatiana’s mother believes, “even the most impoverished of souls…have an inner landscape.” And Tatiana’s soul is far from impoverished. Her inner landscape is intricate and interesting.

Second, and perhaps more important, one might consider that Tatiana is not, in fact, the novel’s main character: the city of Berlin is.

West Side Gallery, Berlin Wall / photo by Paul Mannix

Everything returns to Berlin–to its history, its multiple births and deaths, and all of the conflicts in between. It is no coincidence that Tatiana’s employer is working on a project about the “phenomenology of space, specifically in Berlin.” (Late in the novel, in a scene I will not divulge, Weiss is called an “old Jew,” but overall, his Jewish background is curiously underexplored for a novel set in Germany that so emphasizes a character of his age. For that matter, Tatiana’s own Jewish background—suggested mainly from the details that her family owns the largest Jewish deli in Mexico City and Tatiana’s remark that she “never imagined it would happen but here I was, in a country whose very right to exist had often been a subject of debate over dinner”—doesn’t receive very much attention, either.)

For it is Berlin—and its troubled history—that rests at the focus of Doktor Weiss’s past and present preoccupations (and therefore, Tatiana’s transcriptions):

I had yet to find a Berlin-themed bibliography that didn’t list the name Friedrich Weiss beside the titles of his most revered books: Berlin: The Wounded City; Walter Benjamin & Joseph Roth, Berlin Chroniclers Between Wars; Musings from Both Sides of the Iron Curtain.

And it is through her work for Doktor Weiss that Tatiana learns about the Geisterbahnhöfe, or ghost stations, “as West Berliners called the dimly lit, disused stations in East Berlin, which the West Berlin U-Bahn and S-Bahn trains used to cross without stopping,” and “an amusement park in Treptow, otherwise known as the Kulturpark Plänterwarld, lifespan 1969-1989. Yet another closed and crumbling landmark of the former GDR.” For example.

Brandenburg Gate, Berlin / photo by Paul Mannix

But even outside the hours she spends working for Doktor Weiss, Tatiana seems to encounter more of the city’s “problematic places” (her employer’s term) than she does its citizens. During her very first visit to the city with her family back in 1986–a time, Tatiana recalls in the book’s opening words, “when the Reichstag was little more than a burnt, skeletal silhouette of its former self and the Brandenburg Gate obstructed passage rather than granted it…when the moral remains of the city bobbed up to the surface and floated like driftwood before sinking back down to the seabed to further splinter and rot”–Tatiana became convinced that she’d seen Adolf Hitler right there on the U-Bahn.

The book is littered with references to different Berlin neighborhoods, to an array of straßes and platzes, to various S-Bahn and U-Bahn stations. Some life (or possibly death) force animates many of the locales where Tatiana finds herself, whether she’s walking within a particular neighborhood or, far less frequently, attending a party or going on a date. (I haven’t yet decided which is more disturbing: the party-related episode in an underground bowling alley allegedly frequented by Nazis, or the date scene that takes place under the moonlight among the 2711 concrete slabs of the city’s new Holocaust Memorial.)

Holocaust Memorial, Berlin / by Siemar

Holocaust Memorial, Berlin (inside) / photo by Ulla2004

This is a novel that warrants multiple readings. I’ve already read it twice, and I anticipate that I’ll return to it before too long. I am simply convinced that, like the city in which it takes place, this novel holds layers of stories, some on the surface, some buried, and some far above the ground. In this review, I have, I suspect, captured only a very few of them.

Further Resources

subway station where divide between West and East Berlin used to be / photo by tinou bao

– Read the first chapter of Book of Clouds on NYTimes.com, and pick up your copy from a local independent bookseller.

– Listen to Chloe Aridjis read another excerpt from the novel, this one focused on the “ghost stations,” adapted for NPR’s Berlin Stories series.

– Earlier in 2009, Aridjis contributed this “portrait” of her father, writer Homero Aridjis, for Granta.com.

– You’ll find interviews with Chloe Aridjis on Bookslut and in Night Train magazine. See also this profile in the UK-based Jewish Chronicle.