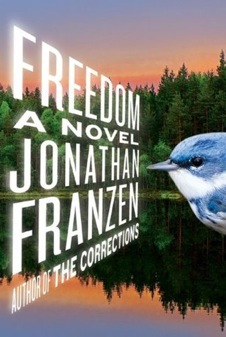

The hoopla surrounding Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) has been spectacular. To recap very quickly: Franzen was the first living novelist to make the cover of Time since Stephen King, ten years ago; President Obama received an advance reader copy of Freedom; there were rapturous pre-release reviews; then the Franzenfreude response to those reviews; the novel was chosen for Oprah’s Book Club (after everything that happened with The Corrections); eighty thousand copies of the U.K. edition were printed with an unfinished version of the manuscript; someone snatched Franzen’s glasses from his face at a party in London and held them briefly for ransom; and most recently, there was “the great American snub” by the National Book Award committee. One rather expects an Onion headline along the lines of MEDIA CELEBRITY PENS NOVEL BETWEEN PUBLICITY STUNTS.

The hoopla surrounding Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) has been spectacular. To recap very quickly: Franzen was the first living novelist to make the cover of Time since Stephen King, ten years ago; President Obama received an advance reader copy of Freedom; there were rapturous pre-release reviews; then the Franzenfreude response to those reviews; the novel was chosen for Oprah’s Book Club (after everything that happened with The Corrections); eighty thousand copies of the U.K. edition were printed with an unfinished version of the manuscript; someone snatched Franzen’s glasses from his face at a party in London and held them briefly for ransom; and most recently, there was “the great American snub” by the National Book Award committee. One rather expects an Onion headline along the lines of MEDIA CELEBRITY PENS NOVEL BETWEEN PUBLICITY STUNTS.

It’d be understandable if the above craziness made a reader reluctant to pick up Freedom right now, given that (to spread this aspect of the Franzenfreude meme:) so many good books go unnoticed and unread. But Freedom is not a book that’s going to disappear when the hype does. If you’re put off at present, just wait five or ten years: as long as we have bookstores, Freedom will be on their shelves. One reason the novel will outlive its time and place is its success in capturing them. When the world is different enough that people will want to remember what the ‘00s were like for a certain cross-section of Americans, Freedom will be first on the list of books they turn to. Capturing the social and political élan, as he showed with The Corrections, is one of Franzen’s great strengths.

It’d be understandable if the above craziness made a reader reluctant to pick up Freedom right now, given that (to spread this aspect of the Franzenfreude meme:) so many good books go unnoticed and unread. But Freedom is not a book that’s going to disappear when the hype does. If you’re put off at present, just wait five or ten years: as long as we have bookstores, Freedom will be on their shelves. One reason the novel will outlive its time and place is its success in capturing them. When the world is different enough that people will want to remember what the ‘00s were like for a certain cross-section of Americans, Freedom will be first on the list of books they turn to. Capturing the social and political élan, as he showed with The Corrections, is one of Franzen’s great strengths.

Freedom opens with a condensed overview of the book itself, told from the perspective of the Berglunds’ neighbors, and ending with this assessment: “I don’t think they’ve figured out yet how to live.” This opening section, in which the Berglunds—Patty and Walter, and later their two children, Joey and Jessica—are presented from such remove, flirts with caricature, as Franzen gives us pretty  generic Yuppie Gentrifiers. But this initial distance allows Franzen one of his great recurring tropes: presenting characters who appear either unlikable or flat, and then, by delving into their pasts and psyches and writing in a close third-person, revealing their rich, complicated lives underneath. Pretty quickly we understand that Patty and Walter aren’t generic Yuppie Gentrifiers, and neither is anyone else. The forces of millennial middle-class America are hard at work on the Berglunds, but the family doesn’t get reduced to props in an argument Franzen is making. While the Berglunds, like so many people, really don’t know how to live, their particular brand of not knowing is unique and compelling.

generic Yuppie Gentrifiers. But this initial distance allows Franzen one of his great recurring tropes: presenting characters who appear either unlikable or flat, and then, by delving into their pasts and psyches and writing in a close third-person, revealing their rich, complicated lives underneath. Pretty quickly we understand that Patty and Walter aren’t generic Yuppie Gentrifiers, and neither is anyone else. The forces of millennial middle-class America are hard at work on the Berglunds, but the family doesn’t get reduced to props in an argument Franzen is making. While the Berglunds, like so many people, really don’t know how to live, their particular brand of not knowing is unique and compelling.

Indeed, the characters are so real and consciousness-saturating that Freedom might make reading another novel temporarily unadvisable. The pages of Freedom turn quickly, and while I read the book in a few days several weeks ago, the characters have dominated my mental space to such an extent that I had to literally go spend time looking through my bookshelves to recall what I’d read in the months before and after (out of respect for those authors, I won’t name them here).

But as realized as the characters and writing are, they aren’t without incongruity. The book’s glaring stylistic flaw is that Patty, who writes an autobiography, “Mistakes Were Made,” at the suggestion of her therapist, is (probably) too good a writer for her character. And her writing is (definitely) too similar in style to the narration of the rest of the book (it’s even in third-person), leaving the prose  indistinguishable. An example will emphasize this point: In September I attended Franzen’s conversation with Keri Miller for Minnesota Public Radio’s Talking Volumes series. I was pleased when he read from the scene where Patty and Walter first meet because it ends with a psychological insight that is quintessential Franzen. Here’s a selection from the end of their first encounter:

indistinguishable. An example will emphasize this point: In September I attended Franzen’s conversation with Keri Miller for Minnesota Public Radio’s Talking Volumes series. I was pleased when he read from the scene where Patty and Walter first meet because it ends with a psychological insight that is quintessential Franzen. Here’s a selection from the end of their first encounter:

“There’s something wrong with me. I love all my other friends, but I feel like there’s always a wall between us. Like they’re all one kind of person and I’m another kind of person. More competitive and selfish. Less good, basically. Somehow I always end up feeling like I’m pretending when I’m around them. I don’t have to pretend anything with Eliza. I can just be myself and still be better than her. I mean, I’m not dumb. I can see she’s a fucked-up person. But some part of me loves being around her. Do you sometimes feel like that with Richard?”

“No,” Walter said. “He’s actually very unpleasant to be around, a lot of the time. There’s just something I loved about him at very first sight, when we were freshmen. He’s totally dedicated to his music, but he’s also intellectually curious. I admire that.”

“That’s because you’re probably a genuinely nice person,” Patty said. “You love him for himself, not for how he makes you feel. That’s probably the difference between you and me.”

“But you seem like a genuinely nice person!” Walter said.

Patty knew, in her heart, that he was wrong in his impression of her. And the mistake she went on to make, the really big life mistake, was to go along with Walter’s version of her in spite of knowing that it wasn’t right. He seemed so certain of her goodness that eventually he wore her down.

It’s for paragraphs like that last one, when the narrator steps back and pegs his characters’ motivations and deceptions, that I read Franzen. So I was surprised, later, returning to the book, to see that this passage falls right in the middle of Patty’s autobiography. But if Patty’s analytic assessment draws attention to the artifice of the novel, so be it. After all, what Franzen has done here is craft a really wonderful novel. Even more so than in The Corrections, in Freedom Franzen has distilled the tenor of the times (to borrow his phrase) and the stuff of real literature into a spirited page-turner.