Reading Steve Amick’s second book, Nothing but a Smile (Pantheon, 2009), occasions reflection on what makes a superb novel. Required are characters we obsess over between readings, expertly drawn characters with whom we fall in love or hate with a passion denied in our normal, non-fictional lives. Such emotional involvement hinges on an author’s ability to give each character a distinct voice. It should be possible to open any page, read a few sentences, and recognize which character is acting or being addressed. Arc, in turn, structures plot, and plot is driven by tension. A master craftsman introduces tension early, produces it in every chapter, and keeps readers turning pages. Perhaps most integral to great work, however, is a narrative voice that is not only clear and precise, but also beautiful, an aesthetic that appeals to mind, heart, and soul. Additionally, in the case of an historical novel like Nothing but a Smile, the author must master the idiom of the period in a way that is lively and current so as not to alienate the contemporary reader.

Reading Steve Amick’s second book, Nothing but a Smile (Pantheon, 2009), occasions reflection on what makes a superb novel. Required are characters we obsess over between readings, expertly drawn characters with whom we fall in love or hate with a passion denied in our normal, non-fictional lives. Such emotional involvement hinges on an author’s ability to give each character a distinct voice. It should be possible to open any page, read a few sentences, and recognize which character is acting or being addressed. Arc, in turn, structures plot, and plot is driven by tension. A master craftsman introduces tension early, produces it in every chapter, and keeps readers turning pages. Perhaps most integral to great work, however, is a narrative voice that is not only clear and precise, but also beautiful, an aesthetic that appeals to mind, heart, and soul. Additionally, in the case of an historical novel like Nothing but a Smile, the author must master the idiom of the period in a way that is lively and current so as not to alienate the contemporary reader.

If these are some of the qualities that define a superb literary work, then Steve Amick has succeeded wonderfully in Nothing but a Smile.

The novel opens in June of 1944, with Winton (“Wink”) S. Dutton, a promising young cartoonist in civilian life, walking the streets of Chicago. Wink is home from the war early, his drawing hand having been mangled when, hung-over while doing an assignment for Yank Magazine, he misheard an ensign’s instructions and touched a submarine flywheel that he should have simply drawn. But prior to shipping back home, Wink had promised his buddy, Bill (“Chesty”) Chesterton, to look up his wife, Sal, in Chicago, so he might tell her how faithful Chesty has been to her, and how much he loves her. And right away, Amick has readers worrying over their meeting; the bleached bones of an affair have been set out in a row.

That wariness is magnified when we shift point of view and meet Chesty’s wife, who is bravely holding down the fort in Chicago. The fort is the camera shop (inherited from her father), which she and Chesty ran together before the war. Soft, blond, and attractive, Sal is, in the idiom of the day, “one tough cookie.” With the shop on the verge of economic collapse, she gets an idea: why not take semi-nude pictures of herself, using a timing device invented by Chesty, and send them to girlie magazines? Maybe she could make enough dough to preserve the nest until her warrior-hawk returns. The photos are difficult to take, in every sense of the term. Sal’s judgments of herself are harsh: in one photo, “her large nipples…seemed to be staring back at the camera like the wide eyes of an owl”; in another, her attempt at “coy and coquettish” makes her look, “more like she had some sort of intestinal issues, maybe an ulcer or just really bad heart burn.”

Steve Amick / photo by Sharyl Burau

Behind the humor, Amick masterfully portrays the desperateness, confusion, fear, and shattered innocence that only a real war can produce. All of this surfaces in Amick’s exquisitely crafted prose, an example of which occurs in his description of Wink’s first glimpse of Sal.

In little subtle ways, he was finding his mind wasn’t quite his own anymore, this first week back stateside. They’d warned him at the VA this would be the case, and so far, it had been true—nothing huge or fantastic. But readjusting could play tricks on a guy suddenly thrown back in with the civilians. And so it was that for one foggy moment, despite knowing Chesty, despite having held the man’s forehead once when he needed to puke his guts out into some jungle plant behind a Quonset PX, despite knowing full well that the man’s nickname was a shortening of his last, in the moment Wink spotted this woman behind the counter, in the no-nonsense Kate Hepburn style trousersuit that nonetheless failed to disguise her physical assets—she was, in fact, somewhat busty, “chesty”—so it was that for that second of confusion, he had it in his mind that this was the Chesty referred to, in the dusty chalkboard sign in the front window that touted CHESTY’S AMAZING SPECIALS.

And then the confusion passed, and he flushed with embarrassment, thinking of the real Chesty, stuck back in the Pacific somewhere—the stand-up guy so concerned about his wife. Wink busied himself removing his hat—Steady on, soldier—and composed himself quickly.

She had eyes, in fact, like his very own mother’s—green and wise and sharply alive, shrewd eyes—and he focused on them instead and told himself, Her name is Sal … Or Mrs. Chesterton … Or ma’am … and told her who he was and why he was there.

With Dostoevskian precision, Amick thus pulls us into Wink’s mind, exposing his conflicted and confused post-war dilemma: unexpectedly finding the wife of his war buddy tremendously attractive and fighting that attraction with a forced comparison to his mother which, in our post-Freudian world, illustrates the ironic proclivity of defense mechanisms to bring about what they are constructed to avoid. Such a whipsaw effect pervades the novel. Amick makes us want so much for Sal and Wink, but makes us fear what we want.

He does this by exposing, at each turn in the novel, Wink and Sal’s ambivalence over what they’re feeling for each other. We love Wink for his attempt to be honorable and, in loving him, wind up hoping that he and Sal become a couple even though that would mean betraying Chesty. Sal’s need for the “scent of a man,” which drives her into Wink’s awkward arms, but only for as long as it takes to catch his scent, is yet another example. We understand her need and want to see it fulfilled by Wink, even though the moral dilemma it causes is troubling. Amick’s simple, unadorned, prose is the vehicle which directly conveys such raw emotion and conflict to the reader. “She remembered the last time he’d [Wink] told her she was sauced—the night she got a little tipsy…and she unbuttoned his shirt and took a big whiff of him.”

Through the window of that same simple prose that in lesser hands could seem hokey, but in Amick’s is deeply serious, we witness Wink’s blushing discovery of Sal’s extracurricular scheme to save Chesty’s shop; his conversion from a crippled cartoonist into a Pulitzer Prize winning photographic journalist (as well as into the producer, director, and photographer of Sal’s pinup project); the introduction of Sal’s hot-to-trot friend, Reenie, into not only the girlie project but Wink’s romantic life; and arrests for indecency and Chicago mob-style attacks on their growing girlie-mag business – all of which combines to produce page-turning tension in every chapter down to the last few words.

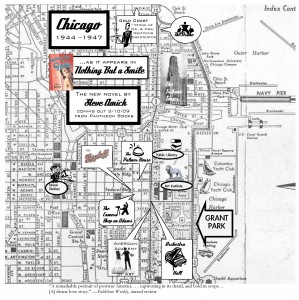

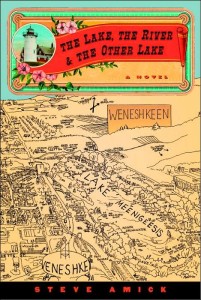

Amick's map of Chicago showing scenes from Nothing But a Smile / from www.steve-amick.com

Any reader with an historical perspective will feel the tension created by a potential love affair in the forties, as well as what an affront it was to the prevailing morays to get into the girlie magazine business, and how dangerous a place Chicago was in the forties due to the prevalence of mob control. Amick taps into our common knowledge of the period, its morays and folkways, to arouse our concern about his characters. The context created by such knowledge prevent his novel from falling into a gee-wiz corniness, the largest potential pitfall of such a novel.

As Amick’s tale unfolds we revel in his love of idiom. We hear about “a Duesie of a plan,” “a load of hooey,” splooge, cheesecake, waxing the dolphin, Keystone Kops, how everything is “jake;” and about characters who are “swell,” who “leg it up” to places, and who are told to “clam up,” or get “socked in the breadbasket.” And we are treated to sentiments that are Amick’s creations, but fit beautifully with the idiom of the forties. As Wink becomes friends with another disabled Vet, someone who’d actually lost a hand, Amick writes:

[Wink] remembered how Uncle Len had always said Feeling better don’t mean feeling better than and Life’s not a misery contest—meaning not to go around grinning because you’ve lost a row of corn to locusts but your neighbor’s lost sight of the sun on account of locusts. And it wasn’t that—it wasn’t just feeling better about things because the guy had a hook while he himself only had some loss of use, dysfunction, as the doctor put it. It wasn’t a misery contest.

Everything about that paragraph indicates the zeitgeist of the early 20th century. We experience the young Wink hearing for the first time his Uncle’s proverbs and listening, also for the first time, to his explanation of their meaning. There’s also the lovely interjection of the word, “dysfunction,” italicized to emphasize a clinical nuance fresh to the forties lexicon. Such meticulous attention to the craft of idiom creates historical verisimilitude: we read this novel through a sepia lens. These textural colorings construct a sociological arc parallel to the arcs of the characters. Over the span of the novel, we witness the subtle and blatant changes in American culture as it evolves from a patriarchal agrarian society with a fairly rigid class system into a society where the sexes are more equal than ever before; a society that not only invents the American Dream, but makes it something that both men and women could achieve and/or fail at.

Amick signs copies of his novel at Nicola's Books / photo from the Ann Arbor Chronicle

And this is why the book matters. Not simply because Amick has created characters we love and obsess over, but because he has produced a psychological record of the post war period of the forties that captures the trials and aspirations of the men who came home and the women who ran the country without them. Nothing but a Smile constitutes a Duesie of a novel, honors the period it depicts, and exemplifies the literary prowess of one of our finest writers.

Further Resources

– Read an excerpt from Nothing But a Smile at b&n.com.

– Peruse pin-up art online at the Great American Pinup Gallery. Or visit the gallery in person (141 Prince St., NY, NY); it’s closed for the summer but will re-open on Sept. 8.

– In addition to his map of Chicago locations in the novel, Amick has also created a map highlighting Ann Arbor, MI, places featured in Nothing but a Smile.

– Find out more about Steve Amick on his website, which includes a helpful lesson on how to pronounce his last name.

– Via Pantheon’s website, browse Amick’s first novel, The Lake, The River, & the Other Lake (a 2005 Book Sense Pick by the ABA and a 2006 Michigan Notable Book).

– Amick’s own site includes a listing of where to find his short fiction as well as a brief preview of what he’s working on now.