We’ve all felt that little rush of connection or electricity or mystery—let’s call it a frisson—from standing in a dusty corner of a used bookstore, flipping through a shoebox of old photos or postcards, and finding something that seems to tell a secret story.

We’ve all felt that little rush of connection or electricity or mystery—let’s call it a frisson—from standing in a dusty corner of a used bookstore, flipping through a shoebox of old photos or postcards, and finding something that seems to tell a secret story.

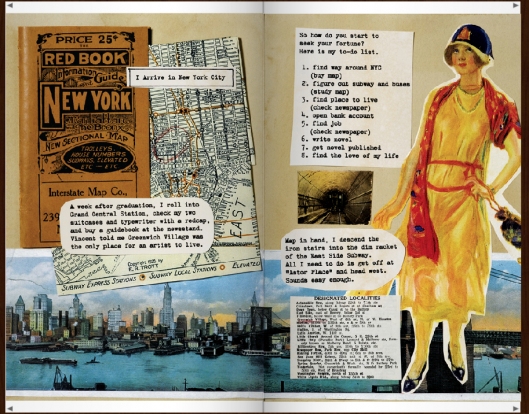

Caroline Preston’s fourth novel, The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt, seeks to recreate that feeling. Preston put together hundreds of pages of hand-cut photos and captions to create the story of her 18-year-old heroine, who receives her father’s Corona typewriter and a blank scrapbook from her mother as a high-school graduation present.

To assemble the materials that would make up Frankie’s life, Preston trolled antique stores and eBay for Bakelite bracelets and ticket stubs, a war medal and a flapper purse, a cigarette holder and a pair of driving glasses, bobby pins and fortune-telling cards. She put these items into a scrapbook: “over 600 pieces of 1920s vintage ephemera, and that’s a lot of stuff,” she says in an interview on her website—and then pasted typewritten text around them to create Frankie’s narrative.

The thrill of that chase is evident in her voice during the interview; it’s the voice of an excited collector, someone who figured out how to translate her passion for ephemera in general and the 1920s in particular into a work of fiction that’s part literary fiction and part graphic novel. The book jacket deems it “a novel in pictures,” but it’s really the typewritten text that forms the story of an 18-year-old girl in 1920, leaving her hometown to see the world.

Through the pages of her scrapbook, readers learn that Frankie Pratt is the smartest girl in her small New Hampshire high school. She initially passes up a scholarship to Vassar because her family can’t afford it, but a failed romance provides an unexpected avenue out of her town and off to college, Greenwich Village, and Paris, not to mention brushes with Charles Lindbergh and Ernest Hemingway.

Frankie is believable and interesting, and it’s fun to spend a few hours in her world, but the unusual format of the book becomes its most interesting character. Imagining the joy it must have brought Preston to assemble this book—the countless hours of searching, the endless eBay surprise packages, the clack of the vintage typewriter, careful cutting and pasting, rubber cement on her hands—might even be a touch more enjoyable than reading the book itself. But for those of us who want to believe that agents and publishers truly are open to novel formats and creative risk-taking, and may be willing to venture into uncharted waters (even with a tried-and-true author), The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt offers a glimmer—a frisson, maybe—of hope.