I write in a shed behind the house—something I love for many reasons, not the smallest of which is that there’s a physical separation from the rest of my life. There’s fifty feet or so from the back door to the shed, space and time enough to clear my head—of diapers, mortgage, weeding—and focus on story. Often enough I’m thinking of my own work on that little walk, but I’m just as frequently chewing on a tiny moment of a story I’m in love with, turning it over and over, trying to understand again what makes it tick.

I teach at a university about thirty minutes from my house, a distance that ought to allow for more thorough examination of those stories I always carry around with me, but I find myself—maybe because of diapers, mortgage, and weeding—returning instead to those tiny slivered moments of time, the places where stories somehow seem to break free even of a third dimension and threaten a fourth. I do very much admire the whole of stories. Don’t get me wrong. But as I think of those stories I have all but memorized—Kevin Canty’s “Why the Sky Turns Red When the Evening Sun Goes Down,” Edward Jones’ “Orange Line Train to Ballston,” Karen Russell’s “Haunting Olivia,” to name a few—I find myself not thinking of the astonishing accomplishment of the whole, but of Canty’s robot boy’s father seeing a coyote up on a ridge, of Jones’ lonely, exhausted mother carrying those phone numbers in her purse, of Russell’s crab boats in that lunatic marina.

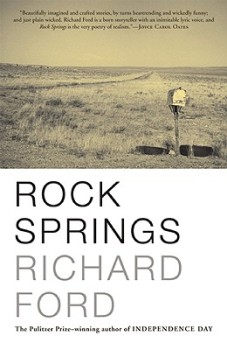

Perhaps no story, though, plays back through my head more often than Richard Ford’s “Rock Springs.” It’s an ungainly, unwieldy thing, a close-one-eye-and-it’s-a-mess sort of story, a story that features, of all things, a gold mine standing in for the American Dream. This is something that not only should not work, but should probably not be attempted, one of those professional-drivers-on-closed-course kind of deals that even professional drivers don’t attempt any more because of CGI. But then you close the other eye, walking to work or driving to school, and there’s that oil light flickering on page 2 or 3, depending on your copy, and there’s Edna and Earl fleeing not only their old lives but themselves, and there’s Earl’s young daughter, Cheryl, in the back seat of that stolen cranberry-red Mercedes with her dog, Little Duke.

Look for the tiniest moments, though. Look for those places when Ford rearranges your idea of what it is to deliver information at speed: “I had a tattoo done on my arm that said FAMOUS TIMES, and Edna bought a Bailey hat with an Indian feather band and a little turquoise-and-silver bracelet for Cheryl, and we made love on the seat of the car in the Quality Court parking lot just as the sun was burning up on the Snake River, and everything seemed then like the end of the rainbow.”

Or, dear reader, the monkey? When Edna tells the story of the monkey she wins in a bar bet and then inadvertently strangles on a doorknob—just putting that to paper makes me marvel at the very idea of it one more time—things take the turn one might imagine: nobody tells a story like that and then rides happily off into the sunset.

Or, dear reader, the monkey? When Edna tells the story of the monkey she wins in a bar bet and then inadvertently strangles on a doorknob—just putting that to paper makes me marvel at the very idea of it one more time—things take the turn one might imagine: nobody tells a story like that and then rides happily off into the sunset.

It’s a story about entropy. About falling further and faster apart. About hanging on even when it’s well past time to hang on. It’s a story about race and capitalism and crime and love and marriage, all the Big American Things—Do you see what happens? This is meant to be some kind of craft talk. I’m supposed to somehow point to the ways in which the story glues itself together, and I can’t do it. “Rock Springs” is a story I understand only through its moments: through the woman and her damaged son in that glowing trailer park, through the cat staring up at Earl like he “was the face of the moon,” through Edna delivering to Earl, after it’s certain they’ll break up, one of the most wrenching, most darkly funny, most beautiful lines I know in all of letters: “Eat your chicken, Earl,” she says. “Then we can go to bed. I’m tired, but I’d like to make love to you anyway. None of this is a matter of not loving you, you know that.” It’s that line, that chicken line, that returns to me again and again. It’s one of the handful of lines from the various stories I know that’s always, always with me, a reminder that even when you are, in fact, chasing the Big Things, your characters still have to eat and want.

And here we’ve reached the end of all this without time for me even to talk about the end of the story, a fiercely triumphant last note that’s as much about literature itself as it is about Earl, more broken now than he was back on the highway when the oil light came on. There he is, down in the parking lot, and he looks back up at the hotel, at Edna and Cheryl, and at us, really: “What would you think a man was doing if you saw him in the middle of the night looking in the windows of cars in the parking lot of the Ramada Inn? Would you think he was trying to get his head cleared? Would you think he was trying to get ready for a day when trouble would come down on him? Would you think his girlfriend was leaving him? Would you think he had a daughter? Would you think he was anybody like you?” He is, of course. He is the car thief inside each and every one of us.