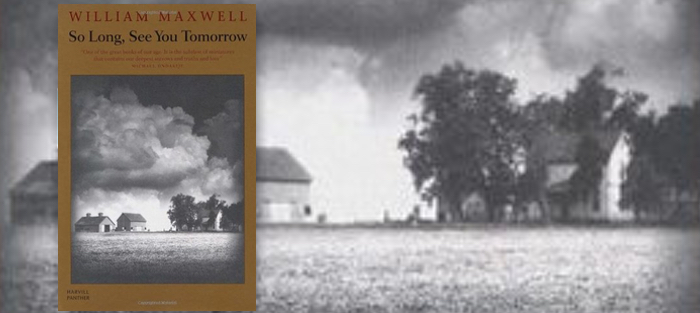

“This memoir, if that’s the right word for it, is a roundabout, futile way of making amends.” With this line—specifically the authorial aside that casts doubt on the very form of the telling—the narrator of William Maxwell’s novella So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980, Knopf), gestures toward the poles of fact and fiction between which the story will eventually move, tethered to the data of individual history and then taking imaginative flight in search of understanding beyond what facts can yield. The result is a dynamic ascent from personal memoir to the more distant and universal perspective of fiction.

“This memoir, if that’s the right word for it, is a roundabout, futile way of making amends.” With this line—specifically the authorial aside that casts doubt on the very form of the telling—the narrator of William Maxwell’s novella So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980, Knopf), gestures toward the poles of fact and fiction between which the story will eventually move, tethered to the data of individual history and then taking imaginative flight in search of understanding beyond what facts can yield. The result is a dynamic ascent from personal memoir to the more distant and universal perspective of fiction.

The facts and feelings of memory begin with the author’s loss of his mother at age ten; the flight of imaginations starts when the narrator and his friend, Cletus, play on a construction site. They walk through non-existent walls and doors, climb rickety ladders, and balance on horizontal two-by-sixes, then part at the end of each day with a casual farewell, giving the novella its title. The construction site’s penetrable walls promise the narrator that he “had found a way to get around the way things were,” referring first to the death of his mother. After infidelity and murder have destroyed Cletus’ life, the narrator ignores his friend in a high-school hallway, leaving the rift that demands reparation and a further need to change the past.

In “Imperishable Maxwell,” an essay published in The New Yorker, John Updike quotes Maxwell saying, “Plot, schmot,” but the slim novella has enough subplots about small-town life and tenant farming to constitute an anthropology of rural Illinois in the ‘20s, as well as characters way too numerous to mention. But it’s not the compelling plot that enables Maxwell to achieve the transcendence I admire and seek in my own work. In “The Art of Fiction # 71,” an interview in the Paris Review, Maxwell says,” I meant [the novella] to be the story of somebody else’s tragedy, but the narrative weight is evenly distributed between the rifle shot on the first page and my mother’s absence.” True, if one sticks to the anchoring parts of the story. But the child’s loss and the adult’s regret are held together by means of a moving metaphor for a feeling well-known to anyone who has suffered unbearable loss: the yearning to stop time and rewind the clock to the moment just before. The promise of the construction site joins forces with a sculpture by Giacometti, “Palace at 4 A.M.” where “thin uprights and horizontal beams” remind the adult narrator of the earlier site. The palace becomes the place where “What is done can be undone,” the place of reparation and reconciliation. While still grounded by facts, Maxwell has caught the wind of imagination to arrive at a place of transcendent understanding. I read closely to see how Maxwell gets from here to there.

Published in 1980, when Maxwell was seventy-two, the novella reflects the author’s belief, growing at the time, that reality makes the best fiction. In the Paris Review interview he says of the novella, “I felt that in this century the first person narrator has to be a character and not just a narrative device. So I used myself as the ‘I’ and the result was two stories, Cletus Smith’s and my own.” Admitting that memory is fallible, he adds, “In any case, in talking about the past we lie with every breath we draw.”

This statement defies most of today’s received conceptions about genres and their boundaries. These fairly recent definitions are products of both hunger for reality and suspicion of lies masquerading as truth. I am as hungry for reality as the next person and often enjoy nuggets of evidence in fiction. When I read journalism or memoir I want to know what really happened and am understandably angry if I have been misled. I recognize the real-world damaging effects of today’s “fake news,” but I don’t think so-called facts can be equated with truth. The reconciliation Maxwell’s narrator seeks with a boy whom he will never see again can only be accomplished in the realm of imagination.

The narrator first takes a journalistic approach to reconstructing the infidelity and murder, consulting newspaper records that could easily be real or invented. When he exhausts this resource, he warns us: “If any part of the following mixture of truth and fiction strikes the reader as unconvincing, he has my permission to disregard it.” I would often like to say the same, and Maxwell gives me courage both to address the reader (how 19th century!) and to discuss the mode of telling within the text. The narrator asks the reader to imagine cards turned up one a time, revealing details about the two tenant farm families and their long friendship, seen mainly through the eyes of Cletus. The series of cards segues into a third-person chapter about a second farm family, headed by the man who had an affair with Cletus’ mother.

From here the point of view seems to change more frequently, but in some ways it’s a return to the first-person omniscient voice of the memories, the one who knows (and doubts) everything and fills in the gaps with invention. The freedom and confidence of Maxwell’s point of view inspires me as a fellow writer, illuminating the ways in which omniscience can lend authority to the teller of the tale, despite the risk of puncturing what John Gardner called “the fictive dream.” Here, for example, the narrator dips into cat-consciousness: “Since they were neither faithful nor obedient themselves, they saw no reason why women should be.” Here, he enters into the point of view of an ant, “who had business on that patch of fair ground,” until Cletus disturbed it with a stick. This playful omniscience moves me from a story of two boys into a larger one of shared loss, experienced by all living creatures, and illustrates the way writers can transcend personal stories.

Cletus moves to town with his mother, now separated from his father, and is no longer allowed to work on the farm. The narrator commands: “Having taken away the dog, take away the kitchen . . .the chores . . .the early morning mist . . .the pitcher and bowl.” This list of imperatives makes no claim to be factual but piles images of loss one on another. The singular takes off again and achieves a universality that only imagination can conjure, while also implicating me as reader in creating the loss. Thus I share both the narrator’s omniscience and his culpability. When both father and son abandon the dog, she howls for three pages in confusion and despair. New Yorker editors took issue with the use of the dog’s point of view when the novella was first published in that magazine, but any child could tell you that a dog who howls for three pages is the saddest thing in the world and, I would add, a perfect slant riff on despair.

At the end of the novella, the “I” returns to walk through and dream of Lincoln. Finally he finds the Cletus of memory, who “walks in the Palace at 4 A.M., . . .With his arms outstretched, like an acrobat on the high wire. And with no net to catch him if he falls.” Construction site and sculpture, joined together, become the perilous place of redemption.

No analysis of Maxwell’s craft can give me such a rich, multivalent symbol, but I purloin a few elements for my personal handbook: direct address to the reader and moral implication by means of imperatives; freedom to include a metafictional discussion within the text; and courage to let the point of view wander where it will.

John Updike’s essay faults Maxwell for “abrogating the contract between reader and writer” by standing before the curtain and shifting from memoirist to fabulist. But to me the contemporary understanding of “fact” ignores the many ways we know and the forms that truth can take. Imagination is not just suspension of disbelief but also a method of investigation, a way of knowing and a means of effecting change. Nothing could be more concrete and factual (while rendered with consummate love and sorrow) than Maxwell’s ode to Lincoln, and nothing could reach higher for emotional, moral, and spiritual truth than his tale of loss, love, failure and redemption in the Palace at 4 A.M. This novella has refined my conception of the possible both in writing and in life.