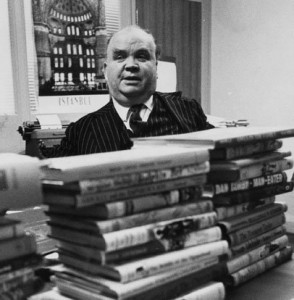

Cyril Connolly

”The more books we read, the clearer it becomes that the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece and that no other task is of any consequence.”

—Cyril Connolly

I think about this quote all the time because it has been taped to my three most recent writing room walls, even though I have never read Cyril Connolly and had to look him up on Wikipedia to tell you anything about him. I learned that he attended Eton and Oxford, that his name was used in a Monty Python skit, and that the American TV series Criminal Minds quoted him as saying “Better to write for yourself and have no public, than to write for the public and have no self.”

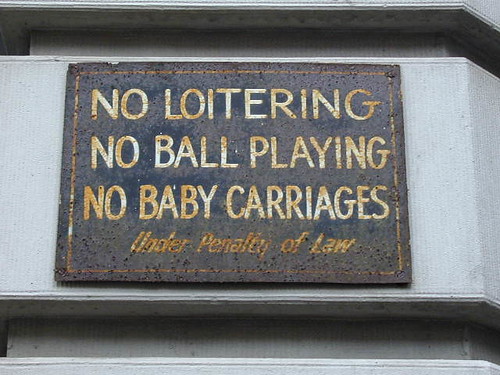

My kind of guy, it sounds like. Connolly never penned a fictional masterpiece, and he wrote about this failure in a book called Enemies of Promise. I might not write a masterpiece either, though I intend to go down swinging; so I pay particular attention to Connolly’s words when I walk into my writing room, close the door, and put on my noise-reducing headphones just in case my kids get up before I finish my morning scribbling. (Connolly also wrote that “There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram [i.e., baby carriage] in the hall,” but I’ll save that discussion for after my kids are grown.)

No other task is of any consequence—the words sting my face and rebuke me for daring to put things like my family ahead of my art. I occasionally argue back at the words on my wall, insisting that true parenting involves a commitment to posterity even deeper than the writer’s path requires. But when I close the door to my writing room, knowing that I’m not on kid duty, I try to make my time count so I can make Connolly’s words count. In the writing room, my children don’t compete with attempts to create a masterpiece; but emailing, applying for teaching jobs, and fantasy home shopping in places where I might teach do compete with those attempts. Even high-minded endeavors, like writing for Fiction Writers Review, can be seen as mere procrastination. Right now, as I write this essay with the quote staring down over my left shoulder at my computer screen, I feel like I’m betraying Connolly and sapping whatever energy it might take to write a masterpiece.

No other task is of any consequence—the words sting my face and rebuke me for daring to put things like my family ahead of my art. I occasionally argue back at the words on my wall, insisting that true parenting involves a commitment to posterity even deeper than the writer’s path requires. But when I close the door to my writing room, knowing that I’m not on kid duty, I try to make my time count so I can make Connolly’s words count. In the writing room, my children don’t compete with attempts to create a masterpiece; but emailing, applying for teaching jobs, and fantasy home shopping in places where I might teach do compete with those attempts. Even high-minded endeavors, like writing for Fiction Writers Review, can be seen as mere procrastination. Right now, as I write this essay with the quote staring down over my left shoulder at my computer screen, I feel like I’m betraying Connolly and sapping whatever energy it might take to write a masterpiece.

Maybe this aspect of my conscience—the always un-helpful one that berates me for all I have never accomplished—wants to dissuade me from writing at all so that it can support its own self-defeating agenda. Maybe it knows something I don’t, and wants to save me from wasting my time in the frivolous pursuit of masterpieces. Or it could be translating, in its own clumsy way, for the part of me that just might write a masterpiece someday and wants me to stop wasting precious computer time. Would Connolly tell me to stop writing about writing, even though he himself made his name as a critic? Would he tell me to neglect my own children in my pursuit of art?

This quote perplexes me, as does my relationship to it. For years I thought about it in terms of what I do in my writing room—the daily discipline, the daily rituals—because it seemed easier to honor those words in the tight context of the room rather than in the broader context of my life. But lately I’ve been thinking about the big implications of what Connolly says, particularly about my relationships to the novels I’ve written that sit on shelves, forlorn and unpublished and likely to stay that way because I failed them.

Yes, failed them. I didn’t do so by spending insufficient time on them, by taking care of my kids, or by writing essays about writing; instead I failed them by not treating them like masterpieces. This isn’t to say that they would have been masterpieces had I treated them as such—I doubt it, since both of them have their flaws—but I certainly didn’t believe in them enough to give them a fair shake at becoming masterpieces. I rewrote them both almost obsessively, so that by the time they entered the world of literary business (read: when they went to agents) I was so worn out from those rewrites that I didn’t have the stamina to hold my ground on agents’ editorial suggestions. I let both novels twist in the wind as I tried to get them into shape for a sale.

Making this subplot stronger and that one nonexistent. Axing character A and making character C a little darker, character D a little sunnier. I could do any kind of rewrites that my agents (one for each novel) requested, but I ultimately lost my grip on both manuscripts as I tried to turn them into books that might sell. With the first one, I even got revision notes from a book doctor (paid for by the big, famous agency) designed to make the book more of a psychological thriller. With the second one, my agent ask me to revisit the female protagonist to make her more sympathetic and provide her with a clearer personal redemption at novel’s end.

Making this subplot stronger and that one nonexistent. Axing character A and making character C a little darker, character D a little sunnier. I could do any kind of rewrites that my agents (one for each novel) requested, but I ultimately lost my grip on both manuscripts as I tried to turn them into books that might sell. With the first one, I even got revision notes from a book doctor (paid for by the big, famous agency) designed to make the book more of a psychological thriller. With the second one, my agent ask me to revisit the female protagonist to make her more sympathetic and provide her with a clearer personal redemption at novel’s end.

I did these things with unquestioning gusto, like a brown-nosing sycophant desperate to get a raise or a promotion. Yet I’m not sure I did them particularly well, since both novels died on the vine with all parties unsatisfied: the agents not loving them enough to give them their all, the author not loving them enough to fight for their identity, and the novels themselves—the ultimate losers in both situations—made lukewarm through my halfhearted attempts to please more than one master. Agent “breakups” followed, and in both cases I tried to make the novels my own again. This process didn’t work out any better because I didn’t really know my novels anymore. I had tried to dress them up, to make them into something they weren’t, and when that failed I changed the shapes of their bodies, the color and texture of their skins. It’s no wonder that, when I tried to make them my own again, they resisted.

The lessons in all of this for me are tough to swallow. Hardest to choke down is the knowledge that my books are not an easy sell, and that my relationship to the businesses of agenting and publishing may always be tricky. Ultimately there’s not so much I can do about that, since I can’t change people’s minds for long. But I can change my own mind, and this is where the lesson that I have to swallow (again and again, it seems) about my unpublished novels aligns with the Cyril Connolly quote that looks down from my writing room wall. I need to treat my books-in-waiting with more love and respect, and even if they aren’t masterpieces, I can at least make sure that I’m not the one who prevents them from being so. I’ve got to serve the book, and that means not letting myself get sucked into daydreams of pay dirt (or at least publication). It means not getting desperate, not being so quick to compromise, not letting myself get away from the true function of a writer: to write that masterpiece or die trying.

Whether people call our books masterpieces or not is out of our hands, but how we feel about those books is entirely up to us. The emotional hue of this Connolly quote has changed for me over time—encouraging, admonishing, snotty, guilt-inducing—but I hope that in writing this essay I can make it mean something more useful and tender. When I see it on my wall, I want it to help me love my books more, to protect then and nurture them as I would my children. I shouldn’t want to squash my novels’ dreams any more than I want to squash my children’s. Instead I should demand from myself that I show these books respect, giving them tough love when I must and leeway when I must.

It’s not much to ask, really. And if I look at Cyril Connolly’s words in the right light, it gets asked of me every time I sit down to write. No other task is of any consequence—so I must enter into my work with a full knowledge of what that work requires of me. It’s not just time, it’s not just discipline. It’s love and warmheartedness too.

If we writers don’t love our books, who will?

Quotes and Notes is a craft essay series by Steven Wingate. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008. He is currently Visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, MA.

Quotes and Notes is a craft essay series by Steven Wingate. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008. He is currently Visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, MA.