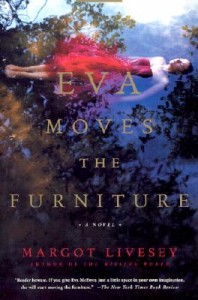

I first met Margot Livesey—Scottish born, but a long time Bostonian—in 2008 at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, where I assisted with her fiction workshop. Having read her fine 2001 novel Eva Moves the Furniture (and, in preparation for the workshop, 1996’s Criminals and 2008’s The House on Fortune Street, I knew I would encounter a mind unlike my own. My characters find themselves in times of chaos and hurlyburly, while Livesey’s are more likely to find themselves in hushed moments when the emotional weight of their worlds shifts infinitesimally. My language leans heavily toward the jagged vernacular, while hers has a precise, formal roundness to it.

I first met Margot Livesey—Scottish born, but a long time Bostonian—in 2008 at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, where I assisted with her fiction workshop. Having read her fine 2001 novel Eva Moves the Furniture (and, in preparation for the workshop, 1996’s Criminals and 2008’s The House on Fortune Street, I knew I would encounter a mind unlike my own. My characters find themselves in times of chaos and hurlyburly, while Livesey’s are more likely to find themselves in hushed moments when the emotional weight of their worlds shifts infinitesimally. My language leans heavily toward the jagged vernacular, while hers has a precise, formal roundness to it.

So naturally I was on the lookout for things I could learn from such a different sensibility, and something quickly and firmly leapt out at me. Livesey urged one student to more freely release basic information about setting and character identity, which the writer had artificially withheld in the interest of creating a small bit of suspense. It takes very little authorial energy to orient the reader in the sensory world of a fiction, she argued—to “take care of the reader,” as she put it—and failing to do so can leave the reader awash in distracting and unnecessary questions.

Since I picked up that phrase from Livesey, I don’t think I’ve run a workshop in which I haven’t used it, and over the years it has taken on a broader meaning for me. Taking care of the reader isn’t merely a matter of dispensing appropriate facts as necessary. It’s a commitment on a writer’s part to maintain the reader/writer relationship, and to honor the fact that readers co-create the work with their own voices and imaginations. Our works reach fruition through a symbiotic relationship with readers that we must attend to and maintain. If we offer them only a murky, imprecise experience, have we really held up our end of the bargain as writers?

In The Flight of Gemma Hardy, Margot Livesey certainly upholds hers. The novel, as its promotional campaign stresses, is a modern (set predominantly in the early 1960s) take on Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). Though the resemblances are close, including a five-part structure, they are not ponderous or strained. One could labor over the similarities between the characters, such as Brontë’s troubled gentleman Mr. Rochester and Livesey’s troubled gentleman Hugh Sinclair, or Brontë’s ill-fated schoolgirl Helen and Livesey’s ill-fated schoolgirl Miriam. But such comparisons are unnecessary when taking in The Flight of Gemma Hardy, and looking for them instead of letting Livesey’s tale live on its own merely distracts from it.

In The Flight of Gemma Hardy, Margot Livesey certainly upholds hers. The novel, as its promotional campaign stresses, is a modern (set predominantly in the early 1960s) take on Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). Though the resemblances are close, including a five-part structure, they are not ponderous or strained. One could labor over the similarities between the characters, such as Brontë’s troubled gentleman Mr. Rochester and Livesey’s troubled gentleman Hugh Sinclair, or Brontë’s ill-fated schoolgirl Helen and Livesey’s ill-fated schoolgirl Miriam. But such comparisons are unnecessary when taking in The Flight of Gemma Hardy, and looking for them instead of letting Livesey’s tale live on its own merely distracts from it.

The book’s eponymous heroine Gemma, orphaned spawn of a Scottish mother and an Icelandic father, is in trouble from the start. Thrust into her aunt’s protection when her beloved uncle dies, she is treated as a servant girl and worse. The first movement of the novel, which covers Gemma’s escape from her adoptive family, filled me with unease over her physical and emotional safety in ways I did not expect. She is also a spooky, elvish girl, tending toward a receptivity to the supernatural that Livesey calls “second sight.” The first impression one gets of Gemma is of someone who will be frequently on the run, a delicate but scrappy survivor with no real place in the world who will land on her feet and create one.

Livesey might easily have pluralized the word Flight in her title, since her heroine is so continually escaping. She flees her family for a new kind of oppressiveness as a “charity student” (a euphemism for child laborer) at a girls’ boarding school, and must escape that when the school closes. She finds work as a governess on Scotland’s remote Orkney Islands, caring for the niece of banker/landowner Hugh Sinclair, whose clutches she also escapes. Her string of flights eventually brings her to Iceland, where she connects to the birth family she barely knew and had long since forgotten.

Throughout the book, Livesey gives us terrific atmospheres in which Gemma’s drama can unfold: the aunt’s house is positively Gothic, the boarding school Dickensian with lost hopes, the Orkney Islands packed with stark beauty. Publicity buzz on The Flight of Gemma Hardy calls it a “breakthrough book” for Livesey, and there’s no reason it shouldn’t be. It’s ambitious—not many writers among us would risk treading on Charlotte Brontë’s toes—and although it leans on Jane Eyre, it insists on having a life of its own that does not depend on its famous predecessor. Livesey has been an outstanding writer for quite a while now, and Gemma is the work of a talented, assiduous novelist truly hitting her stride.

Interview

Steven Wingate: I’ve heard you speak eloquently about a subject most writers shy away from: the mid-career challenge of not “recycling” tropes and themes from your earlier work. The Flight of Gemma Hardy is your seventh novel, and it deals with landscapes (rural Scotland) and human situations (a young girl isolated) that appeared in your earlier books. How did you keep your imagination fresh for this novel, and what about the characters and material made you confident you could pull it off?

Margot Livesey: I had of course written about a young girl in rural Scotland in Eva Moves The Furniture but writing about Gemma felt like a different project in a number of very significant ways. Eva is born in 1920 and grows up into the Second World War. Gemma is born after that war and what her future holds is that great tidal wave of feminism and women’s liberation that swept over Britain and the US in the late sixties and seventies. I purposefully set the novel before that tide took hold, at least in my part of Scotland.

Margot Livesey: I had of course written about a young girl in rural Scotland in Eva Moves The Furniture but writing about Gemma felt like a different project in a number of very significant ways. Eva is born in 1920 and grows up into the Second World War. Gemma is born after that war and what her future holds is that great tidal wave of feminism and women’s liberation that swept over Britain and the US in the late sixties and seventies. I purposefully set the novel before that tide took hold, at least in my part of Scotland.

Perhaps more crucially Gemma faces very immediate and personal adversity. After her uncle dies she is forced to fight her own battles, and she does so with determination. In writing her story I was trying to create not just a character but a heroine.

Advance reading copies of Gemma contain a “Dear Reader” note in which you speak of “writing back to Charlotte Brontë.” Did she continue that correspondence? By this I mean, did your relationship to her (and to Jane Eyre) as touchstones change over the course of the novel?

From the day I started writing Gemma I have not dared to look back at Jane Eyre but my relationship to the novel has undoubtedly changed. I am even more admiring than I used to be of Brontë’s wonderful use of setting to contain the five acts of her novel. And I love even more, in memory, the poetry of the passages between Rochester and Jane. I am also a little indignant on Jane’s behalf at Rochester’s sometimes cruel teasing and testing of her. Perhaps Brontë felt that was necessary because of how unlikely it was that an aristocrat would marry a governess.

From the day I started writing Gemma I have not dared to look back at Jane Eyre but my relationship to the novel has undoubtedly changed. I am even more admiring than I used to be of Brontë’s wonderful use of setting to contain the five acts of her novel. And I love even more, in memory, the poetry of the passages between Rochester and Jane. I am also a little indignant on Jane’s behalf at Rochester’s sometimes cruel teasing and testing of her. Perhaps Brontë felt that was necessary because of how unlikely it was that an aristocrat would marry a governess.

In this note you also talk about stealing from your own life. What thefts were you aware of when you began the novel, and what thefts did you discover along the way as you worked through the drafts? Do you feel a difference in the way you render conscious and unconscious borrowings?

I knew as I embarked on the novel that I would be making use of my difficult stepmother and the grim boarding school I attended for four years. Only as Gemma began to grow up did I discover that I would be drawing on my deep sense that books and exams were a way to escape my present life. As for the role that my romantic life played in my creation of Gemma’s, I think that’s best left to the reader’s imagination.

The book’s opening is quite propulsive, and gave me a sense of physical fear stronger than any I’d felt from your work before. There’s also more of the natural world in Gemma than I remember elsewhere; a stark Scottish landscape becomes, through the heroine’s observations, almost lush with birds and plants. Did you always conceive of the book as having so much elemental “fight or flight” physicality to it?

What a lovely question! Again I think, I hope, I learned from Brontë and her ability to make each of Jane’s five homes in the novel so vivid and so atmospheric. My father was an ardent bird watcher and it was one of the few activities that we shared. I can still recognise most Scottish birds by flight and song. So it felt natural to make Gemma aware of birds who often seem so much freer than we. And of course this is linked to my desire to create a heroine, a young woman who goes out into the world and notices that world as she encounters dragons and struggles towards wholeness and happiness.

Another Jane hovers over this novel—a certain Ms. Austen—especially in the middle, when Gemma comes dangerously close to a rushed marriage. I think particularly of Mansfield Park because of the analogy between Gemma and Fanny Price, two poor daughters adrift in a class beyond their own. Austen’s works took place at the rise of the bourgeoisie, and Gemma Hardy deals with another soft revolution: the sixties. Did you feel yourself in conversation with Austen as well as Brontë?

I owe much to Austen’s keen sense of the importance of class, an importance that the Brontës, as a family, were always eager to ignore or minimise. Then too there is Austen’s wonderful ability to write satisfying romances that fundamentally depend on her heroines coming into their own.

Midway through the book Gemma has a line: “I shrank from wearing a dress whose history I didn’t know.” That says a lot about her sense of propriety, which makes her rather a prude. Her insistence on propriety often saves her, yet the deeper she gets into her own life story, the more dishonest she becomes. How did you feel about her as you brought her to the threshold of her choices?

Well propriety and honesty are, in my mind, rather different and indeed sometimes at odds. Gemma is troubled by her own dishonesty even as she tries to be responsible and perform whatever duties are demanded of her. But she is also sophisticated enough to realise that living under an assumed name is not the worst kind of lie. I have to confess that I was always, shamelessly, on Gemma’s side as she faces various trials and torments.

What’s your next project? Are you taking any down time, and if so how are you using it?

I am trying to do something that strikes me as hugely challenging: write a novel set in America.