Poetry for Prosers is an occasional column by Katie Umans.

These four recent books of poems should appeal to anyone who loves a good story. Warning: the plots may be absurd or cryptic or surreal—or may slip out the back door when you go looking for them.

Kingdom Animalia (BOA Editions Ltd, 2011)

Kingdom Animalia (BOA Editions Ltd, 2011)

by Aracelis Girmay

Aracelis Girmay’s Kingdom Animalia, borrowing animals for metaphor and mirror, asks how a person can live as the one “pushed or fallen/out of the grave, to live.” The living in her books is big and ecstatic, the contemplations of death also somehow so. Her poems tumble into pleas, odes, and elegies, sometimes seeming to land with the imprint not of the brain but of the heart, at least as it can be summoned through poetry’s music. They are never restrained, jaded, or flattened. The speaker watches “the sea & beach move into each other’s mouths” and cries out “O, god, let us love / like they love.” Because of this largeness, this declarative ripeness in the poems, it’s sometimes easy to overlook the precision and intelligence of smaller images, as in the beginning of “Portrait of the Woman as a Skein,” which asks, startlingly, earnestly: “Tell me what, on earth, / would make you leave your hands / or want to, at the wash-sink? / in the lemon grove? / on the way home from standing, baffled, / in the grocery?” and opens from there.

“& isn’t the heart / an ampersand?” Girmay asks in “&.” Yes. In this book, the heart joins the self to everything it can. The heart exists perhaps only what it can join. The speaker’s loved ones are stretched across countries and continents and generations, so the ampersand is necessary, a symbol both rapturous and rending. At times family includes even people not related to one another, as when the speaker watches an intimate scene between a young man and a distraught woman who is not actually related to him, but who somehow is by the end of the poem.

Girmay’s poems are all about such connections, about the pull of family, the pull of earth, the pull of places one has been, the pull of the body’s own impulses, all the “touches of the disappearing.” Where they pause on politics, as in “Praise Song for the Donkey,” which recalls a moment of destruction in Palestine, it is in the context of how impermanent we already are and just how pointless the acceleration of violence is.

One day, not today, not now, we will be gone

from this earth where we know the gladiolas.

My brother, this noise,

some love [you] I loved

with all my brain, & breath,

will be gone; I’ve been told, today, to consider this

as I ride the long tracks out & dream so goodI see a plant in the window of the house

my brother shares with his love, their shoes. & there

he is, asleep in bed

with this same woman whose long skin

covers all of her bones, in a city called Oakland

& their dreams hang above them

a little like a chandelier

& their teeth flash in the night, oh, body.

—from “Kingdom Animalia”

Something in the Potato Room (Kore Press, 2009)

Something in the Potato Room (Kore Press, 2009)

by Heather Cousins

Though this book is a few years old now, it is well worth bringing to the attention of fiction readers (and all readers) who might have missed it. In Something in the Potato Room, Heather Cousins draws us into a world that is bizarre and full of underside-of-the-rock images: a little bit Edward Gorey, a little bit office satire, and a little bit Heart of Darkness. The poems are bodily—full of saliva and crotches, houses “the color of lips and toenails,” then later mandibles, pearly bones, tendons, headaches.

The lines are like some dark glue that might seep out from the edges of a proper Victorian photograph. In fact, Victorian-style drawings dot the book and occasionally hold the frame of an image a touch longer than the poem.

Written more like a novel than a set of disparate poems, the untitled columns of text follow a protagonist who works at an unnamed museum, the stress of which seems to throw her into a state of hypochondria. She is tended by a cryptic, vaguely sinister doctor who sends her on vacation to clear her head. She buys a house and encounters more menacing mysteries there, but these become, at least, her own. The potato room of the title is a “dark, crumbling walk-in” found downstairs in her new home, one perhaps once used for cold storage. It is in this room that a central gruesome re-birth takes place, propelling the remainder of the book and ferrying the narrator into a kind of purpose with a story that’s all images and yet somehow utterly legible.

I held him. Like sailors

hold oars. Like the starv-

ing hold bread. Like boy

scouts hold knots. He was

pointy and full of scuttles.

He smelled of mushrooms

and placenta. It filled the

small room. Coated us.

An oily dust. My hair and

eyelashes were full of it.

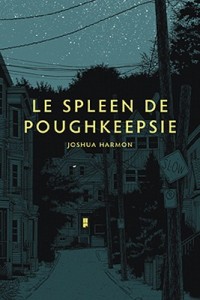

Le Spleen de Poughkeepsie (The University of Akron Press, 2010)

Le Spleen de Poughkeepsie (The University of Akron Press, 2010)

by Joshua Harmon

Here is another slightly older book well worth resurrecting. “Can we just get rid of / Poughkeepsie little by little?” Harmon asks in a rare lighter moment (or maybe it’s the most deadly serious), but before he can get rid of it, he must build it exhaustively, and that he does in eight sections of truly remarkable poetry all devoted to that one city. This is possible and not gimmicky only because Harmon is so talented and does not go simply for a surface catalog of landmarks, nor fall into a detached disdain.

Borrowing openly from literary inspirations as diverse as Baudelaire, The Spoon River Anthology, Homer, and Robert Lowell’s “For the Union Dead,” at times Harmon’s vignettes make me think most of the work of a poet he doesn’t allude to—the T.S. Eliot of “Preludes,” with his “conscience of a blackened street / Impatient to assume the world.” Other times they are more like a Bruce Springsteen song pushed up into slightly more rarefied and intellectual language. Reading them you are word-ported to a stagnant and litter-strewn street, perpetually twilight, often cold, where the sealed-in domestic and commercial rituals lend not a sense of community but a sense of something encrypted, of many people working toward many survivals in some fiercely private way. Poughkeepsie and its people make up a kind of tragedy of self-containment (“We’re cutting down our half of the tree, you can do what you like with yours”).

The no-break look and rhythm of the early long poem “The Poughkeepsiad” may be off-putting to some readers at first. “The Poughkeepsiead” is not only one sentence that spans six pages; it is one sentence that barrels along like an avalanche gathering nouns, never culminating in a verb. Sure there are verbs, small actions, embedded in the lines, but the poem seems trapped (productively, in a literary sense) in “a terrain of nearly unbearable enjambment,” to use Ann Lauterbach’s astute assessment on the back cover. It can certainly seem intimidating, as if one would need a flash of instant large-scale understanding to match its ambition, but if you can shake that feeling and submit to the poem’s moments, you will find each astounding in its own right, from the “wire cart/loaded with the music of aluminum / cans” to the “traffic-struck doe kicking limply / beside the road” or someone sleeping “through gruesome / histories of endurance like an eyelash stuck to a cheek.”

For capturing a sense of place, far more often fiction’s work, it is hard to think of a book of poems that is more successful. As animated by Harmon, Poughkeepsie is a realm where knowledge of a place and the visceral feel of it are never far apart, where “it’s going / to get colder: and it gets colder.” At 90+ pages, the book is probably not one to read in a sitting, but open to any page and you’ll find a stunning portrait that speaks volumes about how poems, which so often boast of being timeless and placeless, can also land somewhere and lose nothing.

The automatic garage-door opener

lifts on a prospect of Poughkeepsie:

row of parked cars along curb, man

leaf-blowing each falling leaf,

sumac growing beneath the overpass:

if you’re not part of the problem,

you’re part of the lengthening

tragedy: we see all the others

slipped into the bright shapes of endeavor,

imprints snow slowly fills, but the stray

detours and workarounds of the secret

city inside the more obvious one

elude our plundered adornments

and church-bell quarter hours

—from “Two Pastorals”

Lucky Fish

Lucky Fish

by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

(Tupelo Press, 2011)

With Lucky Fish, Aimee Nezhukumatathil makes her second appearance in this column. Considering the critical acclaim she is enjoying, this is probably the least of her recent accomplishments, but I think it says something about the reliable accessibility and charm of her voice, coupled with a joyous curiosity that can be appreciated by poets and prosers alike.

The bright and sun-struck poems of Lucky Fish seem at first to be pure Neruda-like odes to fruits and critters and to all that can be projected upon them, so pomegranates scattered from a stolen tree are the “stormy and still-beating hearts” of the original owners and stars in the sky are “cola-colored.” So the speaker says to a lover “I point my pistil / & blade of leaves to you.” But what’s most satisfying in these poems, and where Nezhukumatathil parts ways from the lusty and satisfied Neruda, is that they are not always pleasure-seeking. Sometimes they are inquisitive, often compassionate, sometimes even gently accusatory. These worlds don’t belong to us. They have their own meaning first, before we read our own onto them. The poems are inhabited, too, by a melancholy note, represented by disconsolate petting zoo animals and caged great apes and a fortune telling parrot who guesses that those to whom it tells less welcome fortunes might “tear [its] red beak / in two angry pieces / like a pistachio.”

The poems lean, too, into the magical, as when a flower eats a farmer in “Corpse Flower” or a boy transforms into a bird in “The Feathered Cape of Kechi.” They are fables and fairy tales, yes, but so, the poet suggests, is a honeymoon or motherhood or being a poet, all such delicate and unlikely states, all reliant on the larger narrative we bring to them, what we tell ourselves we are doing—and why.

The poems are not all nature-driven and fable-like. One of the most enjoyable sequences in the book is about Nezhukumatathil’s own identity. In “Dear Amy Nehzooukammyatootill” and “Are All the Break-Ups in Your Poems Real?” she betrays her affection for students trying to figure out her poems and poetry in general. In “Dear Betty Brown,” she strips the affection away to chastise the Texas Representative who suggested that citizens with un-American sounding names should change them to make pronunciation easier for others. The book’s third section is a sustained look at pregnancy, birth, and early motherhood, from a husband who stays “strong as a pepper plant” during his wife’s labor to the early weeks with a baby whose “ears / glow from behind like a church window.” In the haunting poem “The Toy Universe,” Nezhukumatathil zooms out from her son’s toy universe, where “there are smiley faces on trains, / race cars, buses” to the universe of the children “piecing together toy trains / and race cars and buses” in China, living out very different childhoods. In this poem, Nezhukumatathil breaks open the insularity of attentive motherhood. Her poems always seem to be about how much more can be let in, how much farther empathy can extend into world both human and animal, without breaking down our own carefully tended bonds.

She’s been warned not to sleep with moonlight

on her face or she will be taken from her house.She wears eel-skin to protect herself. She tilts

her face to the night sky when no one is looking.

During the eclipse, eels bubble in their darkand secret caves. Toads frenzy in pastures

just outside of town, surrounding the dumb cowsin a wet mess of croak and sizzle.

—from “Eclipse”

Katie Umans is one poet of Two Poet Truffles, a chocolate and poetry enterprise that publishes The Concher. Her first book of poetry, Flock Book, is forthcoming this summer from Dzanc/Black Lawrence Press.

Katie Umans is one poet of Two Poet Truffles, a chocolate and poetry enterprise that publishes The Concher. Her first book of poetry, Flock Book, is forthcoming this summer from Dzanc/Black Lawrence Press.