Sometimes the most disciplined chasers of physical ideals—supple arm muscles, lean legs—slacken their pace. After all, the logic goes, to do so is to enact balance, to practice moderation. They go back for seconds on holidays and return with a plate heaped high, or pad downstairs to rifle through tubs of leftovers in the refrigerator’s glow. The organic, local, small-batch devotee occasionally indulges in something commercially produced, but oh, the guilt!

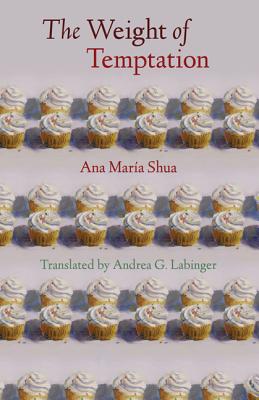

In her new novel, Argentine writer Ana Maria Shua observes the poised calculations and helpless unraveling that constitute one woman’s relationship with food. Marina Ruben (whose last name recalls the famed painter of voluptuous forms) is overweight. The outline of her life, Shua suggests, is comfortable, even satisfying. Her home and work lives are steady, marked by routine and love. But her weight (205 pounds and 7 ounces at the beginning of the novel) troubles her. The feeling of inhabiting her body, and the reality of her scale’s daily readings, are uncomfortable. Her usual weight loss strategy involves some new variety of diet or—less effective, but more visceral—fasting.

Marina enters the story in the midst of one of these fasts. After a long day of this rigorous practice, she slides, slowly at first, and then more rapidly and instinctually, toward urgent consumption. The array of food and drink she consumes, one item after the other, paints a portrait of faltering restraint: fat-free yogurt, tea, hard-boiled egg, rice cake, a piece of potato omelet, tea, four sugar cookies, chocolate cake, bread and butter, cold cuts, the end of a block of cheese, shredded cheese mixed with cream, tea. Later, out to dinner with her husband, she wishes she were fasting again. There, too, she eats with somber compulsion, and resolves to finally sign up for The Reeds, an expensive weight-loss barracks run by a steely guru called The Professor.

Most of the book takes place at The Reeds. The plot hits familiar marks of dystopian literature: a distant nexus of power; fearful masses; tiny, twilight acts of rebellion; and the confrontation of a gleaming ideal. But these fearful masses have voluntarily signed up. The problem the campers hope to remedy is one, they believe, of excessive consumption. The uncomfortable irony is that in order to rid themselves of excessive habits, they must first pay an exorbitant fee to enter The Reeds. The equation goes something like this: excess consumption plus excess purging of capital equals moderation borne of excessive self-control.

Translator Andrea Labinger’s prose style—methodical, matter-of-fact, almost dutiful—supports the novel’s narrative of enforced discipline and routine. The Professor sets up opportunities for learning-via-humiliation during focus group sessions with all campers. In such scenes, a camper engages in a one-way dialogue with The Professor, which culminates in an unusually frightening display, though we are assured that “there’s never been any evidence that the Professor has killed a good client”:

From his suit pocket, the Professor extracted a package of sugar-frosted puff-pastry cookies, opened it, and placed it on a chair. Cookies: flour, sugar, fat, a kind of collective sigh, combining terror and desire, filled the room. Esteban, dressed in a green uniform that made him look like a nurse, walked over. He was a man of indeterminate age, with skin stretched tight across his face and the tiny eyes of the obese.

Although the campers exercise excessively; eat little; endure humiliation and terror (The Professor threatens Esteban with a loaded gun when he reaches for a cookie, then praises his ability to exert self-control), daily life still contains some concessions to the ordinary:

No radios or cell phones were allowed in The Reeds, but musical equipment, records, magazines, and certain books—those that passed inspection—were.

The arrangement at The Reeds, remember, is technically voluntary, so a few reminders of the outside world seem fitting, if ironic, tributes to individual choice. This is a prison campers may leave at any time, though they will lose a large, unspecified sum of money if they do. When campers near an ideal weight, they must live and function in nature on their own for several days in the Survival program. Thereafter, the newly slimmed may return to The Reeds as Tutors, reformed over-eaters who enforce The Professor’s benevolently hostile agenda.

What differentiates Shua’s novel from other dystopian works is the particular oppression of her survivors. A reader’s empathetic response to campers who barely want to stop their excessive eating seems to have little in common, thematically, with narratives of police states and the inescapable exteriority of mass oppression. In The Weight of Temptation, Shua attempts to interrogate what she presumes to be readers’ own unrecognized emotional biases against the camper’s struggles. Crying in her husband’s arms before she checks herself into The Reeds, Marina voices this bias herself: “She imagines this scene as an objective observer might and feels ridiculous. Fat people feel ridiculous in their joy and in their sorrow.” Shua successfully conveys the poignant specificity of all struggles toward ideal selves by detailing the minutiae—both physical and psychological—of the process, if not the progress, of reformation.

Further Links and Resources

- Buy a copy of The Weight of Temptation from an independent bookstore via Indiebound.

- Read more about Ana Maria Shua’s work in English on Words Without Borders or in Spanish on her website.