“The first is outwardly very plain, but serious and clever…. The second is handsome, slim, well made…. My third son is handsome too, but not in a way I appreciate…. The seventh son belongs to me perhaps more than all the others….”

“The first is outwardly very plain, but serious and clever…. The second is handsome, slim, well made…. My third son is handsome too, but not in a way I appreciate…. The seventh son belongs to me perhaps more than all the others….”

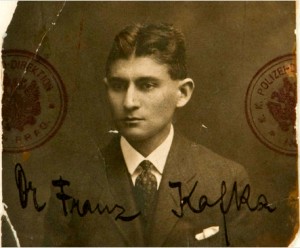

–Franz Kafka, “My Eleven Sons” (translated by Willa and Edwin Muir)

I write this after finishing a draft of a novel but before throwing myself into the next major project, a writer’s limbo that I can never, despite my promises, make last as long as I hope. It’s a great time to catch up on reading, I tell myself, and to give myself a break from the heavy lifting to revisit those smaller projects—stories, reviews, essays, poems—that have been stalled on the runway, or that I never put my best efforts into finishing. I’ll pull out the gestating novel ideas too, just to see if I’m ready for them yet. Sometimes I take all of these projects out of their notebooks or boxes to find that they’re still as awful as before, or still one-thought wonders that feel deader than sponges on the page. Some titillate me, but I’m not ready to engage. Some feel too skeletal to work on without ruining. They will either win the contest to be my next project, or they’ll return to their notebooks or boxes awhile longer, to wait for another attempt at Frankensteinian reanimation. Others simply fail to thrive.

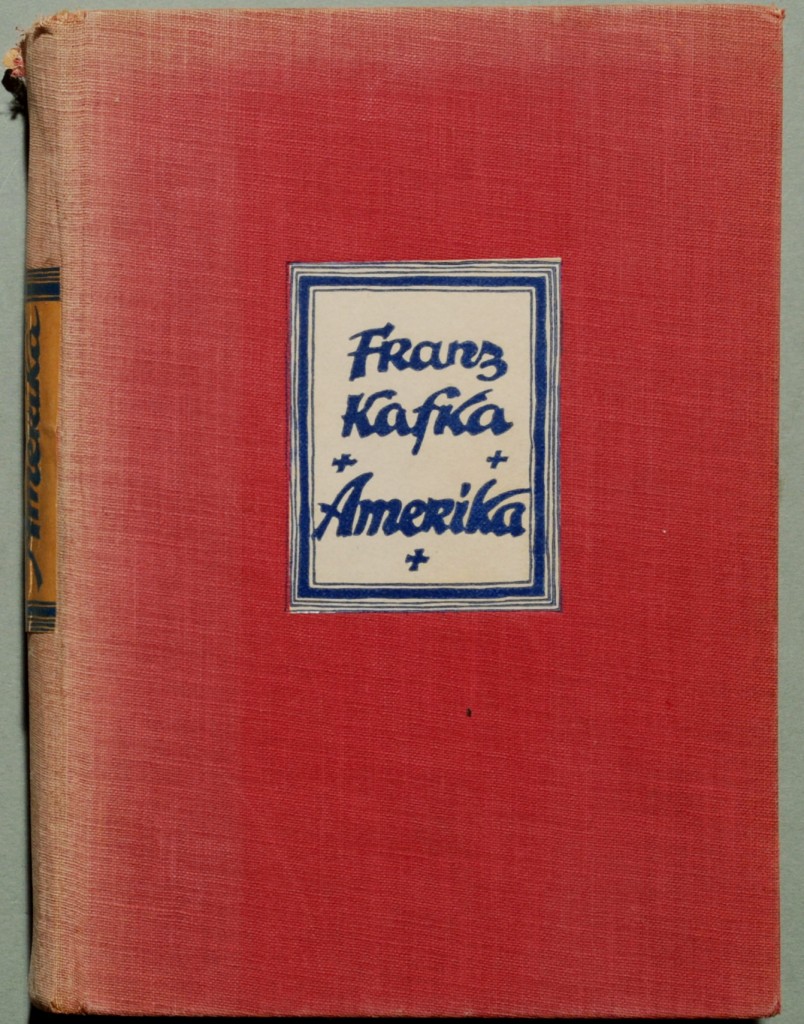

No matter who wins the contest, I have different relationships with each project—which leads me to Franz Kafka, a writer who has fallen out of vogue these days for reasons I don’t quite understand. One of his short stories, “My Eleven Sons,” can be read as an inventory of his various works-in-progress and the tale of his relationships with them over time.

Kafka isn’t always charitable. One of his sons “is like a man who makes a wonderful take-off from the ground, cleaves in the air like a swallow, and after all comes down helplessly in a desert waste, a nothing.” Another “admitted belonging to our family, yet knew that he also belonged to another which he has lost forever.” No doubt we’ve all had pieces like these—beings that spring forth from us, but that we know only dimly, if at all.

Thinking about Kafka’s eleven sons also made me re-examine my own relationship to my works-in-progress, not in terms of the individual pieces, but in terms of overall process. The transition from “no project” to “next project” is too melodramatic for my own taste, but my ritual is purgative and helps me build momentum going into the next big project, like a pinball zooming back toward the flippers. So I’m sticking with it, at least until I find something better, and I plan to revel in all its aspects as long as it allows me.

Aspect One: The Simultaneous Desire to Work on Everything

I come out of big projects with a peculiar blend of exhaustion and manic energy that leads me to think I have unlimited time to work on every project I’ve ever dreamed of. Without the previous project to hijack all my time, I imagine that I’ll be able to take on everything: ideas in their infancy that need architectural work, critical pieces that need a spot of research, ideas for stories I like taking notes on but never actually feel the need to write. In my mind, everything is on the table and I could go in any direction.

But that’s not true. In reality, I simply need to put everything on the table so I can assess what draws my attention most. Is it the small project whose time has come? The “someday” novel that tells me it’s finally time to write a first draft? Whatever process we develop to move ourselves from project to project will naturally involve some kind of signaling that tells us we’re ready to deal with the next child in line; it’s worthwhile to cultivate an awareness of what that signal is and how it rises. For me, it’s voice. Until I hear a clear, distinct voice in my head, offering me sentences, I know that none of my projects are ready for me—nor I for them.

Aspect Two: The Migration of the Computer Files

When I’m in a big project, I tend to use my laptop; my desktop has become mostly a storage unit. I’m happiest when the laptop is lean and mean, containing only the projects I’m actively working on—both my main course and my side dishes. Several side projects (reviews, blog postings, etc.) will get finished while I work through a big one, but I always leave them on my laptop until I’m ready for a major project migration.

The files, haphazard and sometimes duplicate, get purged and put into folders. They join others of their kind on my desktop, which is a more organized and complete map of my brain and imagination. The laptop gets lean and mean again until the next project takes it over, and the cycle repeats. Impetus, chaos, cleansing, impetus. Whatever work we immerse ourselves in is naturally going to generate a ton of questions for us, and the digital clutter that accumulates on my computer during big projects is useful evidence of those questions. Clearing the desktop is a sign that my imagination is ready for a new set of quandries.

Aspect Three: Shuffling My Bookshelves

I like to use my bookshelves as horizontal spaces where I can lay out working drafts and sticky notes, and they also help me establish my hierarchy of projects. On the top shelf sits my current big project and the one in my “on-deck circle,” waiting for me to take it on next. Almost never does the on-deck project actually become the next big project I work on; it’s simply a placeholder, a way to prioritize and give myself structure. (Note that in this photo, below, there are no notebooks on the top shelf yet. The much messier boxes are safely out of view in my closet.)

The next shelf down contains projects I feel the need to get working on soon; there’s even a rather obsessive-compulsive organizational scheme from left to right, but I won’t get into that. On the bottom shelf are books I feel I’m finished with (though that’s far from certain) and need a publisher for. Above that are back burner projects that (a) need significant blocks of time to structure or flesh out, or (b) are compendiums of small pieces I’ve gathered together in notebooks so they can hang around with those of their own kind, and maybe—by being re-read next to each other, and thus re-contextualized—build into something more cohesive.

Between big projects, these shelves will change every day or two. Something comes out of a box and gets a notebook. Something else gets bumped up a shelf or down a shelf. I frankly love the tactility of the process, since it’s so different from staring at black words on a white page or screen. There’s usually a manic moment of shuffling right before my next project grabs me, as they all compete for attention.

One of them wins out—I find myself imagining its physical spaces, the sounds in its air, the cadence of its sentences, the moods and worldviews of its characters, and it moves to the upper right corner of my top shelf to signify that we are in serious discussion and need to work on our problems right away. The runner-up sits in the on-deck circle until it gets petulant with me for not paying attention, and then I relegate it to a lower shelf in favor of something more patient and cheerful.

Aspect Four: What I Can Write vs. What I Must Write

I’d like to metaphorize this selection process by saying that one of my imaginary children has grabbed me, or has clamored for my attention loudly enough, but the process is subtler and spookier than that. It’s more like the child follows me around, mutely watching everything I do, until it gets into my head. Whatever part of me it comes from switches on and begins to feel urgent; I worry about the things that those characters worry about. The sense images affiliated with that project’s world get stronger and more frequent, and I can immerse myself in that imaginative place for longer.

The longer I can “go under” in that world, the more curious I become about it and the more details I want to know. Then the roles shift and I find myself following my characters around, studying their movements and how they respond to people or environments. When I get frustrated at not knowing what they see, say, and think, I know it’s time to start writing them and put other tales aside. All other metaphorical children need to sit, quiet and out of the way, while this one and I hash it out. After all, this might take some time.

How long it all takes depends on the project, the mood, the constraints. Some of my writerly offspring gobble up a year of my time in which no other projects exist. Some need two months of rapt attention—during which work, friends, and even family fade into the distance—followed by a break from dad. Then comes the no-project blues phase, when I always announce to my family that I’m going to take a month or two off from writing of all kinds.

But, of course, such vacations never happen because the blues reel me into a funk that I can only work my way out of by writing. My wife tells me that I’ve never made it to the three-week mark before I’ve plunged my restless hands back into something.

So it must be, I suppose. We all have our rituals, known and unknown. By the time this piece is posted and its words are before your eyes, I hope to be long down the trail to the next all-consuming project that I won’t be able to escape—or live without.

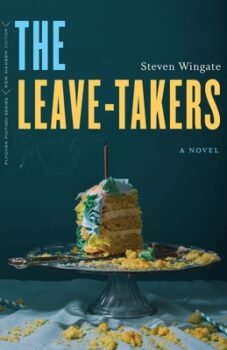

Quotes & Notes is a craft essay series by Contributing Editor Steven Wingate. His debut short story collection, Wifeshopping, won the Bakeless Prize in Fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2008. His prose poem collection Thirty-One Octets: Incantations and Meditations is forthcoming from WordTech Communications/CW Books in late 2013. He is an Assistant Professor at South Dakota State University, where he directs the Great Plain Writers Conference. Visit his author website.

Quotes & Notes is a craft essay series by Contributing Editor Steven Wingate. His debut short story collection, Wifeshopping, won the Bakeless Prize in Fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2008. His prose poem collection Thirty-One Octets: Incantations and Meditations is forthcoming from WordTech Communications/CW Books in late 2013. He is an Assistant Professor at South Dakota State University, where he directs the Great Plain Writers Conference. Visit his author website.