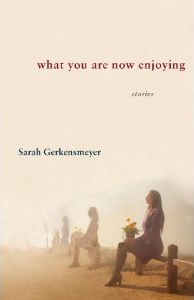

A loquacious infant, a monster, and Wonder Woman sound like a posse going into a bar at the start of a joke, but they are actually characters in Sarah Gerkensmeyer’s debut story collection, What You Are Now Enjoying (Autumn House), which was recently long-listed for The Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award. Add also: polygamists, catfish noodlers, and the female Japanese skin divers called the ama. The eponymous story draws on a world where breastfeeding is a form of therapy; in “Vanishing Point,” people deal with their attached, undeveloped twins; in “The Cellar,” an elderly couple’s memories live in a basement museum, and in “Monster Drinks Chocolate Milk,” a childhood monster has lost his zing. That the collection is not only fascinating but emotionally resonant is evidence of Sarah’s great mind and her sensitivity to how her characters think.

I first met Sarah in Boston last autumn, when we both participated in Grub Street’s Launch Lab program—a sort of marketing boot camp for authors whose books are being published in the coming year. She was raised in Indiana, but now lives in upstate New York, where she’s a professor of creative writing at SUNY Fredonia, and I live in Rhode Island, so we decided to have our discussion in Boston when we were both there for the AWP conference in March. For those readers who went to AWP this year, you will likely recall the snowstorm that settled in for two days, and that the conference center was attached to an upscale shopping mall. I had been mysterious about where we would conduct our interview and, given the nature of her stories, it seemed fitting that access to the borrowed condo where we would have our talk was through a secret door in the middle of the mall. When we got to the door and I pulled out a glowing electronic key, she asked if we were going to be arrested. In fact, we were not, and we sat down beside a window framing the snowstorm to talk about fabulist fiction, men and women, and a case of mistaken identity.

Interview

Maria Mutch: You’re a creative writing teacher, you’re a mother, you’re the Pen Parentis Writing Fellow [2012-2013], so I’m assuming that you have some opinions about how to structure your writing life—can we talk about that before we get to the actual stories?

Sarah Gerkensmeyer: I’ve found that a sense of desperation can be kind of helpful for me to structure writing time. I love teaching and I’ve been teaching pretty much just creative writing for the last eleven years. Sometimes I have difficulty making the transition from an intense focus on the student to an intense focus on my own work, so that’s kind of pushed my schedule around, and of course having children has as well, so one of the things I’ve found I need to rely heavily on are residencies.

With kids I’m only comfortable with doing two-week chunks, and I’ve started to worry that getting huge amounts of writing done in two weeks might affect my writing in a negative way, but I’m really hoping that it’s actually been feeding it. For instance the novel that I’m working on—I set it aside for a year and a half. I came back to it for two weeks in January when I was at the Vermont Studio Center and because I had those two weeks, there was a sense of urgency, but the way that it affected the structure felt so organic, and I realized that my character has this sense of urgency. I think I’ve learned that it’s not this guilty decision of “do I set aside my mothering right now, do I set aside my writing?” I think they both can feed into each other. A lot of the especially short pieces in my collection were written during Charlie’s naps when he was a newborn. So I was writing these weird stories in half hour bursts and thinking, this is fun, and these don’t have to go anywhere, and a few months later I was able to step back and say, I have a collection, and I was lucky enough that other people recognized that. So all of that sense of pressure and the guilt I feel when I go away to conferences, I’ve been able to channel my anxiety into something fruitful, I think, at times.

I’m struck by how your stories run along a domestic thread, but they’re kind of undomesticated domestic stories. Each one contains a surreal or fabulist aspect that radically changes the sense of normalcy in the story. Why did you decide to use fabulist elements?

I can’t point to a conscious moment in my writing life where I thought I needed to start using fabulist elements. I think that “Hank” is my first story that took on a surreal quality and it’s so funny to think back on it because I remember sitting in my little room, and just not being blown away that suddenly this was a story about a baby who speaks. I’m confused by that moment, and the absence of shock, but I’m actually really glad that it happened that way, that it wasn’t this moment where I thought I was making a shift in my writing and things are going to be off-kilter in a very exaggerated way. And with your thoughts of the domestic, I start to wonder if I’m using those strange elements to complicate this idea of comfortable domesticity and status quo. The fantastic is a way for me to challenge our sense of what we’re comfortable with and who we are.

How do the people in your daily environment, your family and friends who aren’t writers, respond to your work?

I think that the most interesting thread for me to think about has been my father as a reader. When he talks about my work, he just talks about the heart of the story and the characters. So that’s been refreshing for me to know that a reader like my father is focusing on the characters, and that’s important to me. I worry sometimes, can the fantastic overshadow my character’s story and the fact that they’re human and experiencing something that we’re all experiencing? So my dad has been a good test-case for that.

Often in stories with traditional fairy tale or magic-realism elements, the reader doesn’t get much insight into what the characters are experiencing. What’s compelling about your stories is the emotional depth. There’s a lot of sensory detail, and there’s this continual element of surprise.

Going along with the sensory detail: Flannery O’Connor! I feel like she’s one of the first writers who was teaching me unofficially, through her work, and she’s one of the writers I rely on when I’m teaching. In one of her essays, “Writing Short Stories,” she talks about convincing through the senses, that good fiction is just pulling us into that world through sensory detail. She makes the point of saying this is especially true for the science fiction writer, and I think this is so interesting for a woman like Flannery O’Connor, who I would have thought would turn her nose up at addressing science fiction in one of her essays. Then when I look at her sensory details, she has pink dirt, and red rivers, and purple trees. I love that she was grounding the reader, but also challenging the reader to look at her worlds in a different way, even though she was writing realist fiction.

Going along with the sensory detail: Flannery O’Connor! I feel like she’s one of the first writers who was teaching me unofficially, through her work, and she’s one of the writers I rely on when I’m teaching. In one of her essays, “Writing Short Stories,” she talks about convincing through the senses, that good fiction is just pulling us into that world through sensory detail. She makes the point of saying this is especially true for the science fiction writer, and I think this is so interesting for a woman like Flannery O’Connor, who I would have thought would turn her nose up at addressing science fiction in one of her essays. Then when I look at her sensory details, she has pink dirt, and red rivers, and purple trees. I love that she was grounding the reader, but also challenging the reader to look at her worlds in a different way, even though she was writing realist fiction.

When you’re approaching each piece, do you begin with the strange element or are you beginning with the ordinary and then walking into the strange?

In the really short pieces, I think it was the strange image that would drive me into the piece, like the sense of momentum was more urgent. For “What You Are Now Enjoying,” I was talking to my best friend about anxiety and depression, and I explained to her how my sister had her first baby and was literally addicted to breast feeding because of the endorphins, and my friend said, “That should be therapy.” So with that story it was the strange that was driving me, but it was this very real discussion of things like anxiety and depression and women and where are our lives going, like this beautiful merging of the two all at once. That’s the moment in the story where I feel like I’m at home and it’s not the chicken or the egg. They’re together because they should be together.

Anxiety and depression are recurring themes. There’s this wonderful part of the story about the baby, Hank: they are at the zoo and they stop to watch a gorilla and you write, “It’s a male, and he was born into captivity.” It’s like everyone in these stories was born into captivity. There’s this strong suburban element running through, of tight constraint. They’re watching the gorilla and the zookeeper says that the gorilla is now being treated for depression. Can you talk about sadness and why that makes an appearance in the stories?

In the scene you just pointed out, I think it’s the character trying to make sense of depression as this separate, strange thing that’s not her, because it’s a gorilla, and I think that for my characters, I’m hoping they can identify with any anxiety, any depression that they’re battling, and they’re able to say this isn’t just something Other. I think I use some of the fantastic elements to push them into that, the possibility for recognition—I don’t think they all come to it. The more I write, the more I realize we’re all dealing with anxiety and depression in our lives; I just think it’s part of being human.

I don’t think, however, that the overriding feeling that I get from the stories is one of sadness. Sometimes you’re intensely funny. In “Dear John,” the husband has, in theory, left, and yet he’s still there, and he has a transformation: he is better looking. You describe his skin as “acquiring a rich olive tone and he is a very tall man now with shoulders that stretch across the horizon.” Then later on, “The sudden hard bulge beneath his shirtsleeves arrives on a Tuesday in October. The white teeth and flexible toes in December, like Christmas.” This brings me to the idea of men in your stories, who are often retreating. There is an absence, or in the case of “Careless Daughters,” there is a husband, but he’s so intentionally bland that he almost doesn’t exist. What comes up for you?

[Laughs] That worries me!

Why does it worry you?

That’s not how I feel about men. I think it makes me realize just how personal and internalized this whole book feels to me. I’m married to a man, and we have a very thriving, important partnership. I don’t mean to shove aside male characters in that way, but it does make me wonder if it’s this freedom of exploring a sense of self and being a woman. For the characters, I think their personal experiences are so intense and immediate that something outside of themselves, a man even, can seem hazy and distant. Interestingly, the “Monster Drinks Chocolate Milk” story came out and I knew right away this is a man, his experience. I want to explore his anxiety, too, and I want him to have a chance to have a direct conversation with that part of him that’s been around forever. That’s definitely a male in my mind—I know I left it open-ended—but that’s a man there.

Let’s talk about that one. In “Monster Drinks Chocolate Milk,” the narrator is sitting on the kitchen counter—

Is that third person?

No, it’s from her point of view, first person.

It’s a guy! In my mind, the narrator is a man.

Now that’s amazing. I was going to ask you about your choice of sticking to all female characters, because you’re either in first person from a woman’s point of view, or you’re in third but sticking very close to the female character. I didn’t understand that the narrator was male—

That’s amazing—I’m confused about how he got in there! In my mind, obviously, it’s your story when you read it, but in the writer’s mind that’s a man.

I was reading an interview with David Foster Wallace and I loved something he said, how in fiction he feels like we’re addressing loneliness and we’re also antagonizing it. And that’s been really helpful for me to think about the loneliness that I see now coming from these characters. I love it when people point out humor because it’s often a surprising moment for me when I wasn’t intending to be funny—but I do see it as trying to push at loneliness and bring it somewhere else. I was chatting with girlfriends about their anxiety, and how in some ways it’s almost like they have a personal relationship with it and sometimes they even are protective of it. It’s an anxious creature as well, and in my mind, “Monster” was that relationship blooming, where the anxiety-provoking beast is also something we need to have a relationship with. And so the way to antagonize this idea is to take anxiety and make it something new and organic and important.

I was reading an interview with David Foster Wallace and I loved something he said, how in fiction he feels like we’re addressing loneliness and we’re also antagonizing it. And that’s been really helpful for me to think about the loneliness that I see now coming from these characters. I love it when people point out humor because it’s often a surprising moment for me when I wasn’t intending to be funny—but I do see it as trying to push at loneliness and bring it somewhere else. I was chatting with girlfriends about their anxiety, and how in some ways it’s almost like they have a personal relationship with it and sometimes they even are protective of it. It’s an anxious creature as well, and in my mind, “Monster” was that relationship blooming, where the anxiety-provoking beast is also something we need to have a relationship with. And so the way to antagonize this idea is to take anxiety and make it something new and organic and important.

Water comes in various forms throughout the book. You have the river where the men go to do catfish noodling, there’s the lake where the twin-people dive as a kind of therapy, there’s the fake aquatic environment of “Edith and the Ocean Dome,” [etc.] Your use of water seems primordial to me, a portal to some other aspect of existence. Do you have apprehensions about water? Does having been raised in the Midwest affect your relationship with water?

I do have apprehension when it comes to water, and I also have deep love—and growing up in the Midwest I’ve always been fascinated with it. There was a point in my childhood when I had five aquariums at the same time. I became really obsessed with the oceans when I was young and ended up taking a scuba diving class at the Y, and it terrified me and I hated going. I was so scared when I was diving in the pool. And I had to do an open-water dive at this lake in Muncie, Indiana. I grew up camping in the Boundary Waters Canoe area and those are some of the best memories of my entire life, but we would also travel so far out, we were literally surrounded by water and it could be dangerous and it was unknown.

Two of the stories feature skin diving: “Vanishing Point” and “Edith and the Ocean Dome.” I want to combine that with “Wonder Woman Grew Up in Nebraska,” because there’s an interesting female empowerment element here. In the story about Wonder Woman, she’s a typical teenager and she’s being coerced into doing stupid things by her friends. Then there are two mentions of the ama divers—you explore them in “Edith.” Edith wants to have an understanding of the ama divers in Japan; they have characteristics that sound to me like superheroes, almost as if they are the actual Wonder Women.

I have this obsession with the ama divers—it started in grad school—I have a really old National Geographic issue and there’s an article in there. I found it in some used bookstore in Ithaca. I have this impulse in me: I want to go to Japan, I want to research, I want to dive with them. I might have a bigger story there that I’d like to tell but I don’t know how much is mine to tell. The Wonder Woman story is the first story where I write about weird things, where I thought, why am I writing about Wonder Woman, and do I have the right to write about her? I’m not a comic book geek, I’m not a comic book scholar. There are so many emotional ties to superheroes, especially right now, where people are seriously considering those stories and how they’re made and do I have a right to this? And then I looked into superhero stories and all these characters have such intense back-stories, like Batman’s parents were murdered when he was eight, Superman’s whole planet is gone. There’s a 1984 issue of a Spiderman comic where we find out that Peter Parker was sexually abused as a kid. I decided that, yes, I have a right to that as a writer because so many of my characters have these radioactive back-stories as well. I had this impulse to give Wonder Woman just a bit of an access to a normal life—even though there is no such a thing—I wanted to rip her out of all that mythology and just let her go through adolescence and all that awkwardness and the awakening. I wanted to give her a break in a weird way.

Can you go further into the different kinds of research you did?

I phrase it as creative research. I feel weird using the word “research” when I talk about it because a lot of times it’s just me in my robe Googling something and watching YouTube videos. As a professor, it’s especially strange for me when I teach classes on form and theory. I’m teaching a type of research that’s very scholarly, and I’m going home and plugging into Wikipedia. The novel I’m working on is intensely research-heavy, it’s a lot of medical research, and I think I got so tripped up in getting it right that the characters fell away. I flew out to the Mayo clinic to meet with the preeminent cardiologist who deals with women with congenital heart disease, and I remember making her go over all my notes from the day I had spent with her at the clinic, and she said, “That’s fine. I’ll go over these notes for you but something for you to think about is this is your story and you can’t lose that sense of story and character and allow the research to dictate that.” So it’s been a weird experience for me because the research I was doing for the collection was more playful and I felt a sense of freedom with it, and at the same time I was doing research for the novel and feeling locked down by it. I just realized, after finishing this book, that I was doing both kinds of research at the same time.

Wonderful. This is a great way to round this up. Can you give us a little more of a direct teaser of what your novel is about?

Basically, when the character came to my mind several years ago, for some reason I was centered on the image of her heart, and I didn’t know if it was a fabulist, magic realism kind of story, and the more I thought about this idea of the heart not being what it should be, I started to think of this idea of a half of a heart. I was drawn to medical research, and I found this condition where patients literally have half of a heart. We’re seeing waves of people with these severe defects surviving into adulthood and the first wave of women asking: is childbearing even possible? Should I get married and have a relationship when death is always here? And that research made me realize that my magical impulses early on in the story were very much connected to the real and to the human experience of this. The protagonist is a young woman in her twenties who has a severe congenital heart defect, and she’s grappling with ideas of motherhood and family, and I think the present scene is only two hours—one or two hours, we’ll see if that changes—so that’s the teaser.

Further Links and Resources

- Visit Sarah Gerkensmeyer’s website.

- Read about images that haunt Sarah at Ron Hogan’s Beatrice.

- Read her story “Dear John” at Guernica.

- Two recent reviews of What You Are Now Enjoying, in The Coffin Factory and Hayden’s Ferry Review.