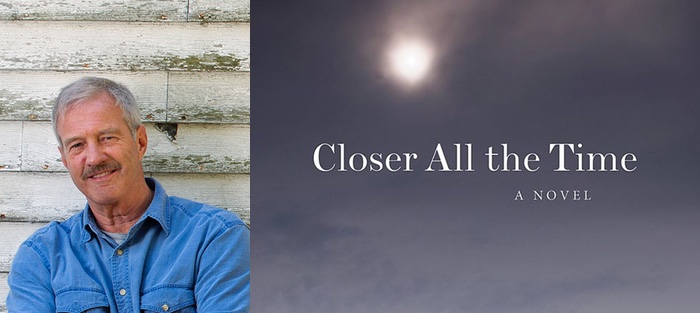

There is nothing flashy about the way Jim Nichols tells stories. And yet, his stories have within their quiet dignity a kind of propulsive readability. Nichols writes honestly about his mythological Maine in plain, patient prose that could boarder on folksy if not for the author’s compassion for his characters. It takes humility to write this way.

Jim Nichols was in his late thirties and working at a tiny regional airport in his native Maine when he noticed on the flight manifest that Norman Mailer would be passing through the next day. When the plane landed, Nichols climbed aboard the tiny plane, cornered Mailer in his seat, and pushed one of his published short stories into the hands of the two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author.

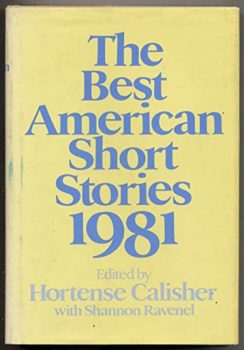

A few days later, Mailer passed back through the airport on his way out of Maine and this time he asked Nichols to see more of his work. At Mailer’s urging, Nichols submitted a story to Esquire, where it was accepted and appeared in the summer reading issue of 1990, accompanied by an introduction from Mailer himself.

When Nichols first book, Slow Monkeys and Other Stories (Carnegie Mellon Press, 2002), appeared, it carried a blurb from Mailer—a surprise considering Nichols is utterly unconnected with New York City or the blurb-machine oft afforded to MFA graduates. “I think I will go so far as to say,” wrote Mailer, “that in Jim Nichols we have one more of a rare breed: the born short story writer.”

A dozen years later, Nichols’s debut novel, Hull Creek (Down East Books, 2011), was published. The narrative follows Troy Hull, a multi-generational Maine lobsterman, and his struggle to keep the family home in a rapidly changing small coastal town. It is a tale of have and have-nots in the vein of John Casey’s classic National Book Award winner Spartina (Knopf, 1989) or William Carpenter’s lesser known but scathingly beautiful The Wooden Nickel (Little Brown, 2002). The novel was a finalist for the 2012 Maine Literary Award for Fiction.

In his latest book, Closer All the Time, recently released by Maine independent publisher Islandport Press, Nichols again celebrates the quotidian as seen in the best novels of Stewart O’Nan or Willy Vlautin or Kent Haruf—though Nichols is much less lyrical and emotionally weighted than Haruf and more reserved like Hemingway in the earliest Nick Adams stories.

Set in the fictional town of Baxter, Maine, in the years between World War II and the computer age, Closer All the Time traces the lives of damaged Vets, good-hearted drunks, clam poachers, broken boxers, damaged young boys, prop place pilots, husbands and wives, single women, and others. They are all, each in the own way, people like the rest of us who struggle profoundly to understand their place in the world.

While published as a novel, Closer All the Time is by no means a traditional approach to the form. Nor is it exactly the collection of short stories that the author first submitted to the publisher for consideration. At his editor’s urging, Nichols revised his manuscript to interconnect the previously stand-alone stories. That said, the “chapters” for the most part eschew a traditional incident-driven short story structure. The “rising action” can be, at times, so subtle as to appear nearly indiscernible.

Closer All the Time is perhaps best described as a succession of vignettes that accumulate to form a kind of community portrait, for it is Nichols’s mythical village of Baxter that tenderly cradles his character’s lives and their stories—and at a moment in our culture when there appears to be no surplus of authenticity, Jim Nichols tells those stories without ego.

[The following interview with Nichols was conducted via email.]

Interview:

Joshua Bodwell: Let’s begin with a process question. How do you write–with a computer or by hand?

Jim Nichols: I can type like the wind, so it’s like thinking directly onto the paper when I’m working on a manuscript. I do prefer a Blackwing pencil for notes and thoughts, though.

And where do you write?

I write in a combination guestroom/office upstairs in my home, usually with two dogs on the bed keeping me company. Sometimes the dogs get impatient and start rolling their eyes, and then occasionally I’m overcome by the aroma from Anne’s cooking downstairs—her own creative outlet is culinary—but generally speaking this works out pretty well.

Can you remember back to a single book or author that excited you so much as a reader it made consider the possibility of being a writer?

I had vague ideas about being a writer from the time I was a kid, but it was reading Hemingway’s short stories in my late thirties that actually spurred me into doing something about it. I was working at the little Rockland airport, and every night I’d have time on my hands, which I spent reading mysteries and science fiction (the kind of books those afore-mentioned vague ideas had to do with). On one of those occasions, I happened instead to pick up a copy of In Our Time that a customer had left behind. And I was lost after reading it. I was stunned that “literature” could be so spare and still be so immediate and thrilling and emotive. I’d never considered writing “literature”—or reading it, for that matter, aside from school assignments—but this little volume completely changed my views.

I had vague ideas about being a writer from the time I was a kid, but it was reading Hemingway’s short stories in my late thirties that actually spurred me into doing something about it. I was working at the little Rockland airport, and every night I’d have time on my hands, which I spent reading mysteries and science fiction (the kind of books those afore-mentioned vague ideas had to do with). On one of those occasions, I happened instead to pick up a copy of In Our Time that a customer had left behind. And I was lost after reading it. I was stunned that “literature” could be so spare and still be so immediate and thrilling and emotive. I’d never considered writing “literature”—or reading it, for that matter, aside from school assignments—but this little volume completely changed my views.

So you weren’t writing stories in your teens or your twenties? Did you go to college, or study writing in an academic setting?

I used to write all the time—I’d write for school newsletters, and I’d write prose and poems in these journals that I kept—but never short stories or novels. I studied History and English at the University of Southern Maine, but not writing. I produced a column for the student newspaper there, and when I switched to Southern Maine Vocational Technical Institute for Marine Biology. I had a serial story going in their student paper about a young Maine lad who was raised by harbor seals, the main purpose of which was to make my friends laugh. After I got serious about writing I went to the Molasses Pond Writers Workshop and to C. Michael Smith’s workshop at Simmons.

Who do you consider your influences, and who are some of your favorite writers? Have you found there’s a difference between your influences and your favorites?

I have a lot of favorite writers. At the very top would be Tobias Wolff, Howard Norman, Elizabeth Strout, Lorrie Moore, Alice Munro, Larry Brown, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Tim O’Brien, and Ernest Hemingway, but I could go on. I could name several contemporary Maine writers who’ve moved into that territory lately, but I wouldn’t want to leave anyone out.

As for influences, it was Hemingway who started it all, and then I think Wolff especially for the power and assurance of his endings, Heinlein and Bradbury for their real-people wit. But there are multitudes. I read competitively, and I think a lot of times I’m influenced because of that. Rick Bass, for example; I don’t like his fictional milieu much, it rings false to me, but I read him and I know other readers love him and that gets me fired up.

Is there a specific Tobias Wolff story that stands out to you when you mention him?

“The Liar” is probably my favorite Wolff story. One of the most brilliant endings ever.

What is about the ending of “The Liar” that you admire? Or about any short story ending you admire?

Hemingway said, “Out of a hundred possible endings, you must choose the inevitable one,” or something close to that, and I think in some cases writers settle for something less, because it often takes so much work to find that perfect ending. But “The Liar” ended in a way that was perfectly true to itself…I wish I knew whether Wolff had it in mind the whole way or whether he had to work to find it.

The story is about a boy who’s been telling dreadful whoppers about family catastrophes ever since he found his father dead in his easy chair. The boy’s mother and the shrink she sends him to try their best to understand and help, but nothing works, he can’t stop, he keeps lying right up to the final scene, which takes place on a bus that’s broken down in a storm. Here he has a sort of lying apotheosis as he regales his fellow stranded passengers with a long tale about being born in Tibet and raised by missionaries, and as they listen in wonder, he somehow manages to transition from English into what—he thinks—is “surely an ancient and holy tongue,” without missing a beat. And as he goes on, fluent and assured, we realize suddenly that he hasn’t really been lying, he’s just been searching for the right way to speak, the language one uses to find answers that don’t seem to exist in English. At least that’s how I see it.

Your first collection, Slow Monkeys and Other Stories, was published thirteen years ago. Do you see any significant differences between the stories in that collection and the stories you’re telling in Closer All the Time?

Your first collection, Slow Monkeys and Other Stories, was published thirteen years ago. Do you see any significant differences between the stories in that collection and the stories you’re telling in Closer All the Time?

The stories in Closer All the Time are interconnected, so in that respect there were other needs—associations and references—that I think made them a little more generous. But also, I think I’ve grown as a writer, I know more.

Generous in their technical scope and range, or more generous in the relationship to character and story?

I’d say in relation to character and story. In order to change the original characters in the short stories to recurring characters in the novel, there were adjustments to be made. For it to work, I had to know and show more about the recurring characters so that I’d have more threads to bring forward for their reappearances.

The emotional tension in your writing is often achieved by the white space you leave, by what you’re your characters aren’t saying. Can you talk about your process of working with this sort of restraint? Do you write long first drafts in order to tighten in successive drafts? Or are your first drafts spare, too?

I do tighten them, through multiple drafts. And each time through, as you know, there’s always something more you can take out, something that might be interesting in and of itself but doesn’t move the story forward. To go back to your previous question, it occurs to me that some of those adjustments I mentioned might have been putting back in some of the superfluous bits. If I remember correctly, I at one point had Johnny Lunden looking out of his apartment over the hardware store and recalling the events of chapter one. I cut that from the story, but brought it back for the novel, used it later in the book.

Both Norman Mailer and New York Times Book Review writer Chris Marquis praised the quality of the dialogue in Slow Monkeys and Other Stories. Mailer wrote your dialogue has the “…fine strain of the just which is always so startling.” Marquis wrote you have an “…unerring ear for dialogue.” How do you approach writing dialogue? Is honest fictional dialogue something you have to arrive at only after many drafts? Do you read your work aloud when you are drafting?

I don’t seem to need a lot of revision with dialogue, for whatever reason. I can hear the characters talking, and they talk like the people I know, and if I try to force them to say something false it stands out. I do read my work aloud, but more for the expository passages, because I’m much more likely to say something awkward or false than my characters are.

What did it mean to you to have Mailer enter your life the way he did?

It was very affirming that he liked what I was doing, and then also it was cool to have an ongoing—if desultory—correspondence with someone who was such a force in American writing. Once he griped that I should enjoy my anonymity while it lasted, because that’s really the only time you can write entirely for yourself.

That same New York Times Book Review piece about Slow Monkeys and Other Stories mentioned your fiction is populated with characters, and men in particular, who aren’t exactly known for making good decisions: “They abandon girlfriends, cheat on wives and fight in bars. From trailer parks or Salvation Army shelters, they rue their predicaments but are powerless to save themselves.” The same could be said of characters in your novel Hull Creek and now of Closer All the Time. What do you think compels you toward the stories you tell?

Come on New York Times, some of them save themselves! But I take the point. It’s like this: I think we’re all walking around in a continual state of longing. We’re all yearning for something. Love, I guess, or connection anyway. But we’re not very good at finding it. We’re turned loose in this world without the necessities to do it easily. Original sin, right? Anyway, we blunder around and get into trouble trying, and that’s what draws my attention, that’s where I like to pick up on the tale. Again, though, not all of the characters are doomed. Sometimes if they’re tough and persistent enough, they find a way, or at least a possibility. I think that’s the case with Johnny Lunden in Closer All the Time; at the end his heart might actually be, if not singing, then at least humming along quietly under its breath, hoping.

Come on New York Times, some of them save themselves! But I take the point. It’s like this: I think we’re all walking around in a continual state of longing. We’re all yearning for something. Love, I guess, or connection anyway. But we’re not very good at finding it. We’re turned loose in this world without the necessities to do it easily. Original sin, right? Anyway, we blunder around and get into trouble trying, and that’s what draws my attention, that’s where I like to pick up on the tale. Again, though, not all of the characters are doomed. Sometimes if they’re tough and persistent enough, they find a way, or at least a possibility. I think that’s the case with Johnny Lunden in Closer All the Time; at the end his heart might actually be, if not singing, then at least humming along quietly under its breath, hoping.

You mention this moment of a character’s blundering around as a place that draws your attention and a place to begin a story. Can you talk a bit about how you decide where/when to begin a story?

Through trial and error, unfortunately. I start with an idea. For example, in Tomi’s chapter the idea that begat the original story was a memory I had of sneaking into the attic and discovering evidence that my mother had been married to another man before she’d married my father. That was far from where the story finally started, and it took probably thirty revisions to get there. Different characters appeared and disappeared along the way, too. The main character changed from a boy to a girl, also.

“Place” appears to be a key element in your fiction. Can you a talk about how Maine and your fictional representation of it inspires your storytelling?

I think it relates to the dialogue question. I see where the characters are while they’re speaking. It involves their activity. They’re somewhere in the world—in Maine, usually, with me—and they’re doing something, which creeps into the picture. In the fist chapter of Closer All the Time, Johnny comes riding into his little town on his motorcycle, which means he has to cross the river, and because it’s his river it’s a part of him and he’s going to notice it. And then he notices the HELP WANTED sign in the town’s new restaurant, because he’s been out looking for a job. But more to your question, I’ve lived in Maine all my life and I love Maine and I’ve knocked around enough in Maine to know whereof I speak with the characters I like to write about; in that respect I know what I’m talking about.

Would these characters and their stories resonate with you in the same way, or compel you in the same way, if they were set somewhere else?

I believe they would, assuming I knew the setting as well as I know Maine.

The vast majority of stories in Closer All the Time are written in the third-person—of the fourteen, just four are first-person. Can you talk about your decisions surrounding point of view when you’re writing a story? Do the stories arrive in your mind with point of view, or do ideas arrive that you then push toward a point of view that suits your telling of the narrative?

The vast majority of stories in Closer All the Time are written in the third-person—of the fourteen, just four are first-person. Can you talk about your decisions surrounding point of view when you’re writing a story? Do the stories arrive in your mind with point of view, or do ideas arrive that you then push toward a point of view that suits your telling of the narrative?

I generally start them in the third-person, it seems to me. But in the course of my revisions I’ll try different narrative voices, changing person and distance, degree of omniscience, that sort of thing, and usually one just sounds better, or more fitting, and that’s the one I stay with. I’ll try everything except the second-person, and I change POVs too, telling the story from different perspectives.

Do you think stories are discovered or created?

I’m really not sure. I’d like to say they’re created, that you start with an image or an action or a bit of dialogue and then build on that until you’ve created something whole and new. But there’s a real process of discovery along the way, and that’s what makes me unsure. Clues turn up as you’re revising that you weren’t aware of, signposts nudging you in the real direction of the story. So maybe in that respect you’re uncovering a story that’s already there, waiting for you to notice the clues.

Let’s talk a bit about the mechanics of Closer All the Time. Did you first write the “chapters” as standalone short stories?

I wrote the stories over several years, and published most of them in magazines along the way. They had entirely disparate casts and locations. But when I submitted them as a collection to Islandport Press, Genevieve Morgan, the fiction editor, suggested I connect the stories in some way that would make the book more of a whole. I gave it a try, worked on it for another five months, put all the stories in the same town and made a river run through it! Some of the characters became the same people at different stages in their lives. It was an intriguing challenge and those signposts I mentioned before started to appear. I saw similarities in characters and situations that I could use. It eventually worked out, and I’m grateful for Genevieve’s suggestion because I think it’s a much better book this way.

Tell me a little about the sections in Closer All the Time named after your character Arnold. The reader is first introduced to him in a third-person story set during his childhood, and then we meet him later in his life with a first-person story. How was point of view important to you in these stories?

I don’t recall any deep thought behind it, really…but Arnold’s first story, as you say, was told in the third-person, and he was mentioned a couple of times in other chapters by other characters, and when he came around again on his own I just wanted to hear what he had to say about things. He’d been characterized by the narrator’s voice and by observation from other characters and this was a third way to get to know him. In the same way, his first-person voice helped out with the characterization of Tomi, Alva, Eric…

So, you’ve published one collection of short stories, one novel, and now this book, which began as stories and morphed into, I guess, a-novel-in-stories. Did you learn anything new about the two forms while working Closer All the Time?

Maybe something to do with those clues and associations. I’m thinking when I go back to the novel I’d put aside, I might write scenes as they come to me and worry about connecting them into a whole later on. It might be a way to let the creative part of the mind have a little more sway. Just banging away and trusting that links and threads will appear to unify it. It’s interesting to think about, anyway.

Your stories have a ring of the real world, and given the tendency of today’s readers to search for an author’s autobiography when reading their fiction, what are your thoughts about how your real life informs your fiction?

I’ve spent most of my life hanging around with non-academic, working class types who are maybe a little on the rough side (without being the desperadoes you see in some blue-collar tales, though they may have desperate moments), and I think these are the people who show up in my fiction. I like them: how they talk, their repartee and wit; how they believe in hard work and independence; how they tend to smirk at foppishness (defensive as the smirking might be); and their pride in their various trades and abilities…to me this type of person and the way they navigate our tricky existence is very interesting.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

Finish the first draft before you worry about fixing anything. If you do, by the time you reach the end you’ll know what the real story is and you won’t have squeezed all the juice out of it along the way trying to fix minutia. I only wish I was better at taking that advice.