Not far into my adolescence, the country singer Faith Hill released a single called “A Baby Changes Everything.” The song—which hovered at the top of the charts for a few weeks in late November before vanishing in the wake of Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies”—was ostensibly about the unplanned pregnancy of a teenage girl, and it was terrifying. “Not a ring on her hand,” Hill crooned, “all her dreams and all her plans, / A baby changes everything.” I wasn’t anticipating the arrival of an infant anytime in my near future, but I had recently become acutely aware of my latent biological ability to father a child, and it horrified me to consider how a single physical act might bring about such life-altering consequences. “Everything? How could a baby possibly change everything?” I began to perceive childbirth as a profoundly disruptive event, one that could upend a person’s entire system of individual values and priorities; babies, then, seemed to me nothing less than tiny harbingers of the personal apocalypse. My parents were not eager to persuade me otherwise.

I had only heard “A Baby Changes Everything” on the radio, in bits and pieces, and it wasn’t until years later that I listened to the song in its entirety to find that it was, in fact, a Christmas tune, featuring the Virgin Mary as its protagonist. This explained all of the “hallelujahs” in the chorus. But even considering its newfound religious significance, Hill’s song retained its weird, unsettling quality, and I credit it with the vague sense of doom that I have since learned to associate with tiny children.

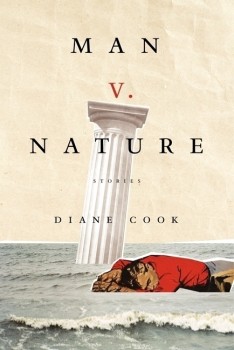

How reassuring, then, that Diane Cook should pick up on this very theme in Man V. Nature, her 2014 collection of short stories that seems equally preoccupied with child-rearing as it does with the end-of-days, conflating the two issues and teasing them apart in a masterful blend of surrealism, fabulist storytelling, and good-old-fashioned apocalyptic fiction. Motherhood is a fraught business in Cook’s tales, complicated from within and without by threats and dangers of all kinds. Here’s the protagonist of “Marrying Up” on going into labor after the collapse of society:

All around us were moans, hands grabbing as we ran. I thought, How can I bring a child into this world?… I almost didn’t make it through the delivery, the child was so large. Its aggressive squirming tore things in me. I was put under.

As the story progresses, the child matures at an incredible rate, “able to reach things on the highest shelf” before learning to speak and bench-pressing between potty-training sessions. His mother’s fears for his safety—and her qualms with raising a child in a dystopia—vanish with the boy’s physical development and are replaced with a growing unease with the boy himself. There is a strangely vampiric quality to her body-builder child, and the story expertly juxtaposes the arc of his increasing strength with that of his mother’s physical decline. “… My boy took every last nutrient,” Cook writes; “he sucked me dry… He grew to an enormous size, a size that scared me, but also delighted me.” Divorced of its bizarre context, this sentiment would be at home in the mouth of any nursing mother. How many parents have marveled at the impossible-seeming growth of their children, stymied by perpetual trips to the GAP in search of clothes to match their son’s latest growth spurt? “They grow up so fast,” one often hears; Cook finds the truth of the expression and magnifies it to fantastic proportions.

Eventually, the threat presented by the boy (prefigured by the violence of his birth) becomes too great for the mother to ignore: her husband, unwilling to remain in the ruins of their city, plans to flee across the mountains with the child, who is now strong enough to fend for himself. The mother, unable to withstand the journey, will either be left behind or abandoned en route. Through the mother’s narration, Cook ruminates on the bleak ironies of motherhood and the passage of time. “How would he remember me?” she wonders. “It was strange to know, looking at them, that they would make it and be fine. And stranger to know that they looked at me and knew I would not. And that we would go anyway.” Again, Cook speaks to a truth that extends beyond the bounds of her story, and I’m reminded of my own mother waving me off at graduation ceremonies and airport terminals, seeming to slip backwards in time even as I move inexorably ahead to a separate future of my own.

Eventually, the threat presented by the boy (prefigured by the violence of his birth) becomes too great for the mother to ignore: her husband, unwilling to remain in the ruins of their city, plans to flee across the mountains with the child, who is now strong enough to fend for himself. The mother, unable to withstand the journey, will either be left behind or abandoned en route. Through the mother’s narration, Cook ruminates on the bleak ironies of motherhood and the passage of time. “How would he remember me?” she wonders. “It was strange to know, looking at them, that they would make it and be fine. And stranger to know that they looked at me and knew I would not. And that we would go anyway.” Again, Cook speaks to a truth that extends beyond the bounds of her story, and I’m reminded of my own mother waving me off at graduation ceremonies and airport terminals, seeming to slip backwards in time even as I move inexorably ahead to a separate future of my own.

But Cook’s story is not yet over. There is, in its closing lines, one last turn. The protagonist, bruised and battered after an altercation with her husband, looks to where her son sleeps “peaceful and trusting” and slips silently from her bed. “I could be brutal too,” she writes, “even in the safety of our once fine home.” And then the story ends. Here, Cook employs the lightest of touches, quietly reminding the reader of the power of a mother’s vengeance and echoing Medea’s catastrophic denouement.

This unease is not unique to “Marrying Up.” The narrator of the fabulist “Somebody’s Baby,” reunited with her daughter years after her kidnapping, is met not with the innocent infant of her memories but a feral girl-child, an “interloper who always seemed unsure where to stand, with her sly stare and twigs in her hair.” Like “Marrying Up,” this story ends with a small physical gesture—this time, a hand placed on the lock of the front door after the girl has snuck out for the night—that suggests a mother’s betrayal without delivering it outright. And “Flotsam,” the short-short-story of a promiscuous young woman named Lydia who is haunted by the inexplicable accumulation of baby clothes in her washing machine, ends similarly. There are no actual children in the story; instead, Cook anthropomorphizes the garbage bag which the protagonist fills with the discarded baby clothing and keeps in the corner of her bedroom. In the story’s final scene, the bag is hurled over a bridge and into the river below, vanishing beneath the rushing waters before it “bursts through the surface again like it’s gasping for air.” As in “Marrying Up,” the implication is one of infanticide, but in displacing the child itself with a representative inanimate object, Cook opens up the story to a wealth of possible interpretations. “She wonders if she should have kept it,” she writes of Lydia, and the story is colored with suggestions of abortion, neglect, and the ache of passed-over opportunities.

Other stories in Man V. Nature, without explicitly tackling questions of childbirth and motherhood, retain a preoccupation with infancy and childhood. Often, as in “The Way the End of Days Should Be” and “Man V. Nature,” the collapse of social order is the occasion for spectacularly childish behavior, triggering a sort of savage regression to the selfish impulses of early childhood (the petty bickering of the latter story’s characters would not sound out-of-place over the tables of an elementary-school cafeteria). “The Not-Needed Forest,” another of Cook’s forays into dystopian fiction, relates the brutal gamesmanship of a band of boys who, marked for death after their twelfth birthdays, escape into the woods and resort to cannibalism, relying on elaborate athletic rituals to determine who will serve as the next meal.

Other stories in Man V. Nature, without explicitly tackling questions of childbirth and motherhood, retain a preoccupation with infancy and childhood. Often, as in “The Way the End of Days Should Be” and “Man V. Nature,” the collapse of social order is the occasion for spectacularly childish behavior, triggering a sort of savage regression to the selfish impulses of early childhood (the petty bickering of the latter story’s characters would not sound out-of-place over the tables of an elementary-school cafeteria). “The Not-Needed Forest,” another of Cook’s forays into dystopian fiction, relates the brutal gamesmanship of a band of boys who, marked for death after their twelfth birthdays, escape into the woods and resort to cannibalism, relying on elaborate athletic rituals to determine who will serve as the next meal.

Cook’s stories span across genres and styles, and while all of them might stretch the boundaries of reality, each remains firmly grounded in the world of truthful storytelling. It may be tempting to unite the pieces in Man V. Nature under the single banner of “fabulist,” but the word seems to imply a sort of didacticism which is nowhere in evidence in this collection. Just as the reader finds herself tempted to draw a one-to-one allegorical connection between elements in the story and the “real world” issue—between the man in “Somebody’s Baby” and SIDS, for example, or the monster in “It’s Coming” and the specter of economic collapse—the narrative shies away, doubling back on itself, throwing up new obstacles to the readers understanding which prevent such easy simplifications and allow for a multiplicity of meanings. The defining quality of great visual art, someone once said (I’m almost certain it was either Rebecca Solnit or Virginia Woolf, two writers for whom a reader of Cook might also profess admiration), is that it allows for interpretation but denies explanation. This seems a fair standard by which great literature, too, may be measured—Man V. Nature, then, is nothing less than great literature, a work which, I hope, will only find itself further deepened in meaning with subsequent readings.