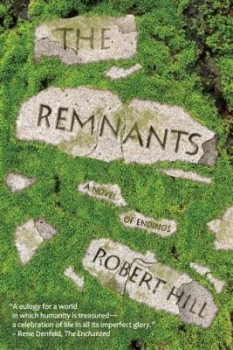

At our branch library, young readers are urged to find their way in a story by using the four w’s and one h: who, when, where, why, and how. Most novels offer up these signposts within a page or two. Open Robert Hill’s new novel, The Remnants (Forest Avenue Press), however, and a reader’s GPS goes into a nervous spin. Searching for coordinates, we enter a whole, new, unfamiliar world, one with its own myths and history—and seemingly on the brink of doom. Adding to the disorientation, the hyper-lexical, hyper-active prose loops and twists as if intent on mystifying. Even when we establish our location as the micro-village of New Eden, the name’s symbolism confirms suspicions that this a place not easily pinpointed on a map.

Journeying into the story, we encounter a similarly perplexing who, characters with cheerfully macaronic names—Onesie Lope and Twosie Lope, Hunko Minton, Jubilee, Carneval, Brisket Whiskerhooven, Agapanthus Saflutis—with a suggestion of the Dickensian: Remedial Bliss, Flummox Belvedere. There is a character called Kennessaw and a tyrannical goat called Chippewa, offering a momentary native American specificity, but they too are part of the hodgepodge that defy geographical location—or, it must be slowly suspected, are gathered as remnants of a world whose defining borders have dissolved.

Similarly, the novel’s when confounds clear answers. Tools are axes, not telephones. Girls wear dresses with pantaloons in houses with parlors and davenports. Characters dunk their heads in rain barrels. There are privies, a malodorous lack of personal hygiene, raccoons, and a conspicuous absence of modernity.

If the what is a birthday tea party in which one character determines to win his life-long love, and the how leads the reader through the town’s dense history, beginning with its nameless “dweller,” these finely-constructed tales of love thwarted, bad luck, incest, revenge, and old age take place in a where that remains oddly elusive. There is talk of bears, of barns. Southernness is implied—a kind of hillbilly subsistence—but this is not Daniel Woodrell’s Ozarks, nor Eudora Welty’s Mississippi, planted firmly in time and place. Hill’s aimless farmer Drells might be distant cousins of the Snopeses, but jaunty wordplay and folktale rhythm rescue New Eden from a descent into the violence and despair of Yoknapatawpha County. Similarly, Flannery O’Connor’s misfits would not feel at home in New Eden, where, despite its biblical nod, a Greek chorus of a narrator keeps up a running commentary, and offers pithy judgments and wisdom that packages the brutal events with a felt sympathy.

Closer in spirit to Allan Gurganus’s fictional Falls, N.C., a small town with a name likewise teleologically ripe for picking, the prose moves in a comparable joyride of excess, metaphor, and wordplay, but Falls’ residents carry Geiger counters trained at calibrating manners, values, eroticism, and their own meticulously observed material culture. The residents of New Eden, in contrast, live as in a tall tale: a boy with a cowlick and long thumbs, a girl help captive by a goat. The themes are large and dark, the actions troubling, the stories’ tragedy held together with masterful control. New Eden seems out of time, a kind of dark Brigadoon. It is perhaps the other side of our Biblical origins, a place post-order, on its own brink of disappearance, a site of myth revealed only in this telling.

Closer in spirit to Allan Gurganus’s fictional Falls, N.C., a small town with a name likewise teleologically ripe for picking, the prose moves in a comparable joyride of excess, metaphor, and wordplay, but Falls’ residents carry Geiger counters trained at calibrating manners, values, eroticism, and their own meticulously observed material culture. The residents of New Eden, in contrast, live as in a tall tale: a boy with a cowlick and long thumbs, a girl help captive by a goat. The themes are large and dark, the actions troubling, the stories’ tragedy held together with masterful control. New Eden seems out of time, a kind of dark Brigadoon. It is perhaps the other side of our Biblical origins, a place post-order, on its own brink of disappearance, a site of myth revealed only in this telling.

Still, the question of where persists, and the voice contributes to this sense of displacement. The first sentence, beginning within the mind of a centenarian named True Bliss, whose long life has been doomed to loneliness, uses an apple seed as a metaphor that hops through a hundred years of True Bliss’s life in a matter of sentences. The narrator–whose identity is another part of the puzzle–hardly takes a breath before hurtling headlong into the whole, tangled yarn. The prose rushes with an energy of an acrobat on espresso, yet always with gymnastic control. Metaphors that seem spontaneous are deftly developed and looped smoothly into whatever follows. With nouns conscripted as verbs—“They’d accident upon discoveries” —the language is peppy and intelligent, with details tucked in so neatly that they accrete and augment with a light touch. But the style’s dazzling, high-wire originality also spares the reader too often, as if with comic bungees, from experiencing the full force of emotional gravity.

Marianne Moore famously declared that imaginary gardens must contain a real toad. Lewis Carroll uses Alice as his; her likeably stubborn literal-mindedness in conflict with Wonderland shows up our own world’s absurdity. In Hills’ first novel, When All is Said and Done (Graywolf, 2006), his playful prose is in service to a story with a very specific setting, a suburb on the outskirts of New York in the 1950’s, with characters living in a world recognizably similar to our own, but illumined by finely, humorously observed detail. Perhaps part of the persistent disorientation in The Remnants is that the imaginary garden of New Eden contains exclusively imaginary toads. This lack of familiar reference creates an effect more cerebral than emotional. It is startling when, briefly, two characters seek medical help in a neighboring town complete with cars, modern buildings, and a hospital marked with a letter H. To reverse Moore’s rule, they seem like imaginary toads in our ordinary world, and as the GPS reconfigures, our interpretative app also whirs into play: perhaps the author means New Eden to represent the forsaken of modernity. As stories largely drawn, though, without such topographic juxtaposition, without an Alice as a guide, we have to make our journey, a little unsure and hyper-vigilant, until the inner logic and recurring themes become the world’s own familiar signposts. The novel is, at heart, a bittersweet love story about left-overs of many kinds, and once a reader trusts the strange terrain, it feels like our own.