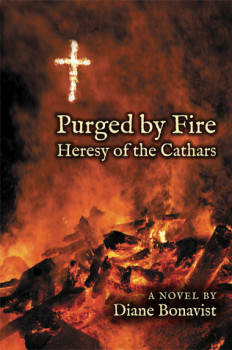

Diane Bonavist’s debut novel, Purged by Fire: Heresy of the Cathars, was published this summer by Bagwyn Books, an imprint of the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. Her novel begins in 1232, after the crusades. When Holy Mother Church’s twenty years of war failed to wipe out heresy, special courts of inquiry, conducted by Dominican monks, were enacted to root it out once and for all. Purged by Fire tells the stories of three defiant people enmeshed in the cruel machinations of the Inquisition: Isarn, who believes he has survived the wars by accepting the Pope’s will and the French rule, until the woman he once saved from death arrives on his doorstep, leading him to question every compromise he has ever made; Marsal, who was once raised to turn the other cheek, but who now wants back what the Catholic Church and the Inquisition have stolen, regardless of cost; and Chrétien, who can scarcely remember his life before he knew and loved Marsal, and who—along with Marsal—will face further decisions and consequences after the Inquisition lays siege to the mountain fortress of Montségur, where the lovers have taken refuge.

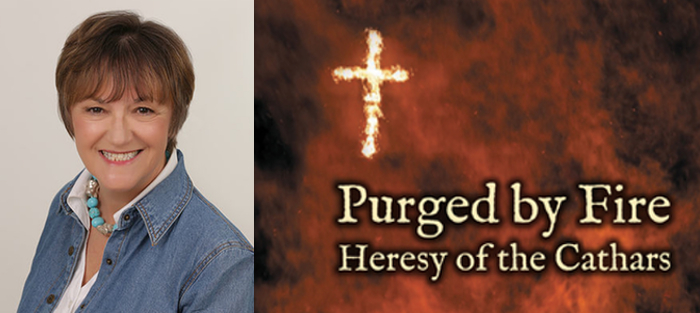

Diane has worked as a technical writer, editor, and indexer. For more than eight years she worked on Tiferet Journal, including three years serving as editor-in-chief. She also conceived of and edited The Tiferet Talk Interviews. Diane’s fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in The Milo Review, Fable Online, The RavensPerch, and Linden Avenue Literary Journal.

Interview:

Donna Baier Stein: What first sparked your interest in the story of the Cathar heresy?

Diane Bonavist: Sixth grade Church History class. We learned about the Albigensian Crusade and the faithful Catholic leader Peter of Aragon, who remained true to the church when the other nobility took the side of the heretics. Aragon would play a minor part in the book I would eventually write years later. For some time I knew I wanted to write about spiritual renegades and Catholic Church history, but I hadn’t a plan. I was newly married and my husband had brought to our pile of books Zoé Oldenbourg’s classic work about the Albigensian Crusade, Massacre at Montségur. That book led to many others and my absorption in the Cathars grew.

How much research was involved in the writing of your novel? Did you find that historical facts limited your imagination at all? Or, were you able to strike a balance between made-up story-telling and what actually happened?

I spent about a year making notes and absorbing the history, literature, and geography of the time before I could write much of anything. This topic was so complicated there were times when I wished I had chosen something a little more straight forward for my first novel. But that’s not how it works. If I hadn’t loved these people and wanted to imagine their story, I couldn’t have written it. But there is truly so little known about the Cathars. There are books written about them, of course, and I was lucky enough to have access to many of them, but there is not a vast library on the subject. The only primary sources are in Latin, and they are the depositions of these people taken by their persecutors, the inquisitors. Historical facts didn’t hinder my imagination; they expanded it. It was falling down a wonderful rabbit hole, finding something new and pursuing it, deciding where in all the history of the Albigensian Crusades and the Cathars and the 13th century I wanted to dwell.

How did your upbringing as a Catholic—and your studies of yoga and other spiritual traditions—figure into your interest in the Cathars?

Born into a Catholic family, I can’t remember a time when there wasn’t church and Christ and all the accouterments of Catholic life. My parents were not “always running down to the church” as my droll mother sometimes remarked about other more devout brethren, but it was church every Sunday and, unfortunately, parochial school. Like many pre-pubescent Catholic girls in the early 1960s, I thought I had a “vocation,” a calling to sisterhood. Well, I did, but it was sisterhood is power—feminism not the nunnery.

Born into a Catholic family, I can’t remember a time when there wasn’t church and Christ and all the accouterments of Catholic life. My parents were not “always running down to the church” as my droll mother sometimes remarked about other more devout brethren, but it was church every Sunday and, unfortunately, parochial school. Like many pre-pubescent Catholic girls in the early 1960s, I thought I had a “vocation,” a calling to sisterhood. Well, I did, but it was sisterhood is power—feminism not the nunnery.

I left the church when I was nineteen. But I was still very interested in god and the great unknown and any door that might lead to it. I read about Eastern religions and began following Paramahansa Yogananda’s path of Kriya Yoga in my mid twenties. Then I wandered out of that and into more mysticism, eastern religions, shamanism, and feminist wiccan, and goddess knowledge. For decades I followed a guru-centered spiritual yoga. These pursuits showed to me that a state of transport in meditation, or tears of unconditional bliss, or mystical dreams, are the same in all practices, as is the jolt of a truth absorbed. Everything I learned from my spiritual studies and experiences went into trying to understand the Cathars.

I probably set out to write a scathing expose of the horrors the Catholic Church committed against the Cathar heretics. Instead, I found compassion for the Church. Every time I got lost in writing this book, I would try to bring it back to my primary question: What is the relationship between this person and their chosen deity?

But your question was, how did all this figure into my interest in the Cathars? I was surprised at how contemporary the Cathars seemed when I first learned about them. Women priests, reincarnation, non-violence, vegetarianism—the Cathar beliefs seemed like many of the same ideas energizing me at that time.

What is your writing schedule like (if you have one)?

The first forty years of my writing life was embroidered around salaried employment, so I got used to writing early in the morning before work, and then a little in early evening if I still had any juice left. Now that I’m retired from the work in captivity world, and my schedule is my own, I still write in the morning and if the work is humming, evening too, and if I’m on fire, weekends. When I’m in a slump, I park the car someplace nice, usually near some water and force out a couple of pages of junk, or I research until I can find my way back in. Anything that will help me reach, again, the place where I throw my leg over the wall and emerge back in that other world. Where I report what I see and feel. Where I roll around in the muck of another time without giving up flush toilets and antibiotics.

What advice would you give new writers of historical fiction?

Decide on a time and place that you want to spend years in. Unless you are writing historical biography, the sense of place and time is going to be the keystone of the book on which you build characters. Anachronisms in an historical novel make us wince; strive for accuracy. Be accurate with language usage, but keep it simple. One of the pleasures of historical fiction is to learn new things; however, don’t be so arcane that you need footnotes. It’s fiction. Likewise, you don’t want to jolt the reader. My writing group wouldn’t let me use the word atom in a story set in ancient Greece, although the word was older than my story and fully appropriate. So even if the word is correct, if it sounds too modern, let it go.

What books did you most frequently return to as you wrote your novel?

I began writing the book some decades back, when it was difficult to get works about the Cathars in English, and even the ones in French weren’t numerous. Fortunately, I lived within walking distance of the best university libraries in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Besides Zoé Oldenbourg’s book, which I mentioned earlier, I returned again and again to the writings of René Nelli, who, last century, helped generate a fresh, bold scholarly discussion about Cathar beliefs and rituals. Joseph Strayer’s The Albigensian Crusade is written in a clear, accessible form that carefully lays out a complicated, multi-layered history. And his thirteen-volume dictionary of the Middle Ages was available at one of the M.I.T. libraries. There were also dozens of bookstores in the neighborhood.

I began writing the book some decades back, when it was difficult to get works about the Cathars in English, and even the ones in French weren’t numerous. Fortunately, I lived within walking distance of the best university libraries in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Besides Zoé Oldenbourg’s book, which I mentioned earlier, I returned again and again to the writings of René Nelli, who, last century, helped generate a fresh, bold scholarly discussion about Cathar beliefs and rituals. Joseph Strayer’s The Albigensian Crusade is written in a clear, accessible form that carefully lays out a complicated, multi-layered history. And his thirteen-volume dictionary of the Middle Ages was available at one of the M.I.T. libraries. There were also dozens of bookstores in the neighborhood.

Next to my desk was my go-to shelf of works on general subjects—Medieval history, gardens, food and households, philosophy, religion, engineering, homosexuality, male and female troubadours. Books like Marc Bloc’s Feudal Society, kept me grounded in my time period—1209 to 1244. While a book such as Braudel’s The Identity of France helped me understand the importance of space and place in France from the historical long view. But this is starting to sound like a bibliography and that’s what I wanted to avoid in my book. I didn’t want to have a lot of keys, glossaries, and so on to explain a complicated piece of history. I wanted it to be comprehensible to a reader who knew nothing about the Cathars and the Catholic Church’s crusade against them. I did use the device of short chronicles in front of each section to try and reground the reader in time and place.

Can you tell us a bit about your journey to publication?

The book I produced twenty years ago quickly found a New York agent, back when that meant something, one who was extremely encouraging and excited. I naively thought, Wow, this could happen. Then it didn’t. Three years later, I found another New York agent who suggested some minor changes and was also enthusiastic about the book, but he couldn’t sell it to any of the major presses. I deleted a hundred pages, combined two characters, and found a new agent—No Sale. Two years ago, I restructured the book, changed some of the POVs and sent it out to a few Indie Presses. Bagwyn Books accepted it for publication.

What are you working on now?

Short stories, a novella about 1957 Cape Cod, and a novel about the ancient world.