It was a beautiful summer evening on Martha’s Vineyard. Donna Baier Stein had asked me to dinner to discuss a new project. I had just begun to tuck into my crab cakes when she invited me to help found a literary press and magazine.

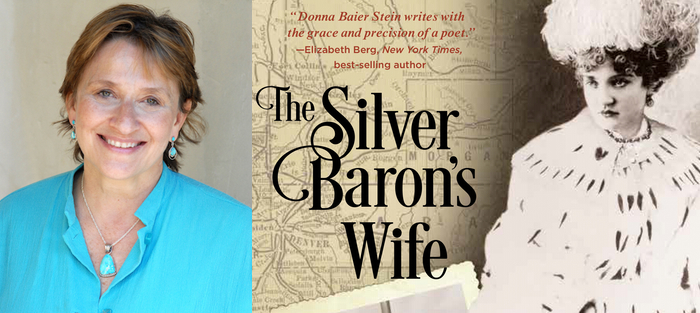

I was wary. I had started a publication some years back and knew how heart/back-breaking such a venture could be. But this was Donna Baier Stein asking. She was a founding editor of Bellevue Literary Review, an alumna of Bread Loaf, the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships for her fiction and poetry. A writer whose work ethic was as powerful as her gifts. When she said she was going to do something, I knew I had to pay attention.

Not too long after our conversation, the literary journal Tiferet was born. Its name comes from the Tree of Life and means “heart, compassion, reconciliation of opposites.” In the twelve years since inception, the journal has expanded to become an active online community for writing, poetry, art, and learning that reaches thousands and seeks to “further meaningful dialogue about what it is to be humane and conscious in today’s often divisive world.”

All of Baier Stein’s writing is imbued with this humanity and consciousness, a radiance that could be called spiritual. Not a puffy-touchy New Age spirituality, but the muscled, intellectual, delving variety that expresses the examination and effort it takes to be a seeking, authentic soul. Yet her writing never bashes the reader with realizations. Rather, she unveils the truth of her characters with a brave, earthy wit and an archer’s eye for hitting the mark.

Her novel, The Silver Baron’s Wife, a fictional re-creation of the life of Colorado’s Baby Doe Tabor, whose rags-to-riches-to-rags story inspired the 1932 film Silver Dollar and the 1956 opera The Ballad of Baby Doe, has just been released by Serving House Books. An earlier version of the novel received the PEN/New England Discovery award. Baier Stein is also the author of the story collection Sympathetic People (Serving House Books, 2013) and the poetry chapbook Sometimes You Sense the Difference (Finishing Line Press, 2012). Her work has appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, Prairie Schooner, Confrontation, and many other journals, as well as having earned three Pushcart nominations and prizes from Kansas Quarterly, Florida Review, and elsewhere. She is also the recipient of a Bread Loaf Scholarship, a Johns Hopkins University MFA fellowship, and more.

Interview:

Diane Bonavist: Could you tell us how you decided on the subject of The Silver Baron’s Wife?

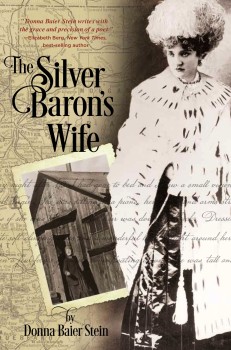

Donna Baier Stein: I first learned about the novel’s main character, Baby Doe Tabor, when I was seven years old. My parents and I vacationed in Colorado many summers, and I still own the postcards we bought on that particular trip. For some reason, the pictures of Lizzie Tabor—one in her ermine coat, one in front of a ramshackle mining cabin—had a magnetic pull on me. Even as a young girl, I somehow knew that the extremes in this woman’s life—of materialism and spirituality—were fascinating. I was also very, very interested to learn that she had written down thousands of her dreams.

Donna Baier Stein: I first learned about the novel’s main character, Baby Doe Tabor, when I was seven years old. My parents and I vacationed in Colorado many summers, and I still own the postcards we bought on that particular trip. For some reason, the pictures of Lizzie Tabor—one in her ermine coat, one in front of a ramshackle mining cabin—had a magnetic pull on me. Even as a young girl, I somehow knew that the extremes in this woman’s life—of materialism and spirituality—were fascinating. I was also very, very interested to learn that she had written down thousands of her dreams.

When did you first know that you wanted to write about Baby Doe Tabor?

I knew I wanted to write a novel and naively assumed that plotting would be a piece of cake if I simply recorded the trajectory of this woman’s life. I bought John Burke’s nonfiction book The Legend of Baby Doe (Putnam, 1974) and highlighted key facts. Too many of them! The first scene I wrote was one of her at age eighty-three, looking back on her life. I only learned much later that a person’s biography does not automatically make a good narrative arc for a novel.

One of the most fascinating things about the character of Baby Doe is her quest for God. Is this element—the spiritual—integral to your writing?

Her quest for God was definitely something that drew me to her, even as a child. I was fascinated to read about the spirit encounters Lizzie claimed to have with Jesus, Mary, and others. I have always been drawn to the “invisible world.” I grew up with a Christian mother and Jewish father and have always been a seeker, I suppose. And those last decades of Baby Doe’s life, when she lived alone, were always what most haunted me. I wanted to believe that she was onto something… that she did receive visionary visits from Jesus, for instance. I don’t know if she did, or if she simply thought she did.

Judy Nolte Temple wrote a fabulous nonfiction book called Baby Doe Tabor: The Madwoman in the Cabin (University of Oklahoma Press, 2007). In that book, she talks about how Lizzie Tabor may have been a true American female mystic or an eccentric—“a madwoman, a mother driven mad with worry, or a rough-draft religious visionary, perhaps even a mystic.” Having had some so-called “peak experiences” in my own life, the question fascinates me on a personal level, as well. What elements of our dream life or spiritual experiences are “real?”

Could you tell us about your research process? How do you decide what parts of a life to focus on?

I have several filing drawers filled with research materials. I visited the Denver Public Library twice, and I’ve been to Leadville and the Matchless Mine numerous times. At times, I felt overwhelmed with the amount of material I had accumulated. At one point I had the Denver Library photocopy dozens of Lizzie’s dreams and transcribed them from her sometimes hard-to-read handwriting. I found and copied old newspaper articles. Saw a performance of Douglas Moore’s opera The Ballad of Baby Doe at the Kennedy Center. This opera in particular focuses on the love triangle between Lizzie Doe, Horace Tabor, and Augusta Tabor. Very little mention is made of the last three and a half decades of Lizzie’s life, and I wanted to change that. I wanted to see Lizzie as a woman in her own right, not just as a young blond woman who had an affair with a married man many years her senior. Because of those last years in the mine, and her careful attention to her interior life, I knew she was far more than a blond floozie.

Still, I found it challenging to decide what parts of her life to focus on because there was so much material.

You also write poetry. Could you talk about how you approach beginning and building a poem, compared to your method of novel and story writing?

I started out by thinking that writing poems and stories would be easier and faster than writing a novel. And in some respects, that remains true. I definitely think that short form fiction is a great way to learn and practice elements of craft. In all three genres, I start out by writing incredibly messy first drafts. I think the biggest thing I’ve learned in this writing life is that it is OK for that first draft to be terrible. As Hemingway said, “All first drafts are *&^#@.” I used to think that writing a messy first draft meant I wasn’t a real writer. Now I know that it’s writing that terrible first draft and then rewriting and rewriting it that makes one a real writer.

I started out by thinking that writing poems and stories would be easier and faster than writing a novel. And in some respects, that remains true. I definitely think that short form fiction is a great way to learn and practice elements of craft. In all three genres, I start out by writing incredibly messy first drafts. I think the biggest thing I’ve learned in this writing life is that it is OK for that first draft to be terrible. As Hemingway said, “All first drafts are *&^#@.” I used to think that writing a messy first draft meant I wasn’t a real writer. Now I know that it’s writing that terrible first draft and then rewriting and rewriting it that makes one a real writer.

You have also written a series of stories based on the paintings of Thomas Hart Benton. How do you move from viewing the painting to making a small world out of it?

Oh, that’s been so much fun. I had been writing a lot of contemporary short fiction and one day sat down with a strong desire to write something really different, far removed from my own life. I looked up to see a Thomas Hart Benton lithograph that hangs in my office. I’m from Kansas City (where Benton lived much of his life), and my parents had bought this lithograph many years ago. It’s called “Spring Tryout.” I started describing what I saw: two boys and a horse in a field, with a small gray farmhouse in the distance. Before I knew it, the boys had a mother back in that farmhouse, who was struggling to wake from a troubling dream. Of course, even though I was writing about a different era (1933) and place (the Midwest), elements of my interior life still popped up in the story.

Speaking of place, the American west plays a role in much of your writing. How did your connection to this part of the country come about, and do you think it will also play a part in your writing going forward?

I was born in Kansas City, Missouri, and lived most of my childhood in Iowa. And as I mentioned, we spent summers in Colorado for many years. I love Colorado, and the Rockies touch a deep part of me that no other elements of the natural world touch. I’ve lived on the East Coast for many decades but on some levels, remain a Midwesterner inside. I just joined a group called Women Writing the West and will be going to their conference for the first time this year. I’m definitely about the Midwest—mostly Missouri and Arkansas—with the current collection of stories based on Thomas Hart Benton paintings.