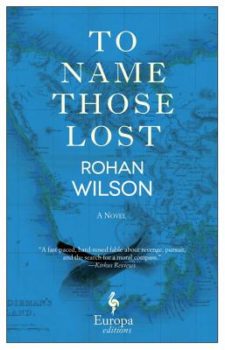

In To Name Those Lost (Europa Editions), Rohan Wilson sets a personal feud in the midst of a town riot. What starts as pushback against railroad regulations erupts into a firestorm of looting and violence as villagers in Launceston, Tasmania, in the summer of 1874, play out the full force of their disenfranchisement. Enter Tom Toosey, reformed prisoner in search of his orphaned son, and Fitheal Flynn, Toosey’s friend-turned-enemy, in search of revenge, accompanied by his disguised daughter. When forces collide, those lost make way for the ones left in their wake. “And the sound of love is to name those lost who lived for others.” Sacrifice is not in vain; the children for whom the lost ones gave their lives live loudly, even if without noise.

Wilson achieves his meaning by relentlessly juxtaposing opposites. The pithy chapter titles (e.g., “The Letter,” “The Shed,” “The Park,” “The Hooded Man”) set the stage for stark encounters. Early in the book, in the chapter “Two Seekers,” Flynn and his hooded daughter stop at a farmhouse where Toosey has just hurt the farmer. They ask the farmer’s wife where Toosey went, but she replies, “I’ll tell you what I see. I see Jacky here needin the surgeon, and I see you with your gun and your hangman over there, mad as rabbits the pair of you, lettin him die. Who’s the murderer? Eh? Who?” She suggests a theme that carries into the rest of the story, that justice begs crime and vice versa; they are opposite sides of the same coin. In the two enemies’ conflict, opposites attract. Flynn wants revenge not for the money Toosey stole from him, but for the principle of retribution. Toosey doesn’t deny his crime but refuses to be a victim because of it. These two are bound by their mutual hateful adamance. They are both sides of the coin, opposites in themselves. As a killer, Toosey finds he’s both less in God’s eyes, and also equipped to be his own master. So, too, hiding his daughter under a hood, Flynn both saves her as well as makes her into something she is not. The jarring effect of Wilson’s tale is that nothing is as it appears.

Wilson achieves his meaning by relentlessly juxtaposing opposites. The pithy chapter titles (e.g., “The Letter,” “The Shed,” “The Park,” “The Hooded Man”) set the stage for stark encounters. Early in the book, in the chapter “Two Seekers,” Flynn and his hooded daughter stop at a farmhouse where Toosey has just hurt the farmer. They ask the farmer’s wife where Toosey went, but she replies, “I’ll tell you what I see. I see Jacky here needin the surgeon, and I see you with your gun and your hangman over there, mad as rabbits the pair of you, lettin him die. Who’s the murderer? Eh? Who?” She suggests a theme that carries into the rest of the story, that justice begs crime and vice versa; they are opposite sides of the same coin. In the two enemies’ conflict, opposites attract. Flynn wants revenge not for the money Toosey stole from him, but for the principle of retribution. Toosey doesn’t deny his crime but refuses to be a victim because of it. These two are bound by their mutual hateful adamance. They are both sides of the coin, opposites in themselves. As a killer, Toosey finds he’s both less in God’s eyes, and also equipped to be his own master. So, too, hiding his daughter under a hood, Flynn both saves her as well as makes her into something she is not. The jarring effect of Wilson’s tale is that nothing is as it appears.

While the two main characters make personal the town’s political conflict, ancillary characters broaden the perspective so that the story is everyman’s. The cast is a colorful assortment of deplorables: fellow orphan to Toosey’s son, Owen, with red hair and a penchant for pickpocketing, Jane Hall has a bad leg and passes as a boy, Chung, the Star of the North Hotel owner welcomes no riffraff but will call a mistress for anyone who’ll pay, and Stewart feeds needy kids for the fee of exhibiting himself to them. We’re drawn into an absurd circus of folks around whom Toosey and Flynn make more sense.

Making heroes of killers and saviors of thieves, Wilson manages to confuse morality while avoiding amorality. This isn’t a Robin Hood story, status quo turned on its head. It is a new system all together. It takes a while to get used to. I was lost through the first few chapters, like being lost in the outback, trying to keep track of who’s who and who did what. But being lost is all part of the new system Wilson builds, of digging into the gritty mess of a conflict in order to come out on the other side. The truth isn’t buried in the past but in those who carry on at the end of the story, like Flynn’s daughter, who, after she removes the hangman’s hood she’s worn, escapes Launceston in a cart full of dead bodies.