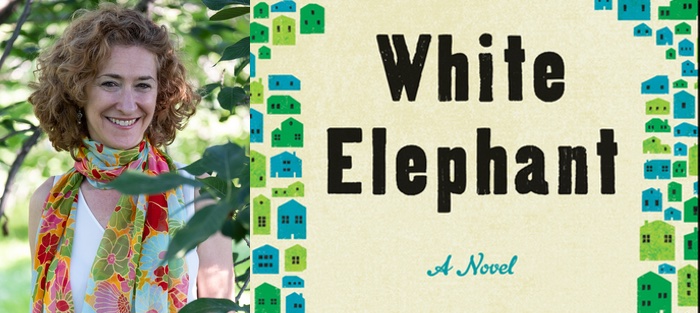

I met Julie Langsdorf earlier this year at an event for D.C.-area writers. As soon as she described the plot of her debut novel, White Elephant (Ecco, 2019), I knew I needed to read it.

When an ostentatious house (the “White Elephant”) pops up in a picturesque, established community and trees mysteriously begin to vanish, discord is fueled, revealing the complexities of modern upper middle-class living. Husbands and wives in seemingly close relationships don’t understand each other and have opposing life goals. Parents with fixed ideas about the manner and environment they want to raise their children, struggle to connect with those children. Teens brought up by thoughtful, loving parents still can’t escape self-doubt, loneliness, and peer pressure.

White Elephant provides insights about the human condition by raising interesting questions: What makes for an idyllic neighborhood? What expectations can one have for married life? What constitutes a perfect upbringing for a child? What does it mean to be tolerant of one’s neighbor? What does it mean to have a fulfilling life?

For all the insights, this novel is never heavy. Every page sparkles with wit, and there are many laugh-out-loud moments. The situations Julie presents are so tension-filled and familiar, the characters so real and relatable, that I found myself sometimes yelling into my book for them to act in certain ways. They generally didn’t take my advice, but I loved them anyway. I have a feeling you will, too.

Julie is a four-time Maryland State Arts Council fiction grant winner. She has two children and lives in Washington, DC.

Julie and I conducted this interview via email.

Interview:

Kate Lemery: How old were you when you first decided you wanted to be a writer, and how long after that did it take you to begin writing? What sorts of things did you write? When did you first think of yourself as a writer?

Julie Langsdorf: I can’t remember a time when I didn’t think of myself as a writer, to be honest. I was a big reader and writer as a child. I plotted out my first novel when I was nine, a pirate tale set on the island in the Dutch West Indies where my mother lived as a child; and, soon after, I wrote a novel whose central character was a beagle named Benjamin Banneker. I don’t know if knew about the “other” Benjamin Banneker or not . . . After college I wrote feature articles for newspapers and magazines until I started writing fiction.

What is your educational background, and how did you learn the craft of writing?

I went to Colgate University for three years, and finished up at Georgetown. I majored in history but I took a lot of English classes as well. I attended American University’s graduate program in creative writing for a year, but I left when I got pregnant with my son and needed to be on bedrest.

What was the best money you ever spent as a writer?

What was the best money you ever spent as a writer?

Money spent on books is always money well spent! Money spent on travel falls in the same category. It helps to get away, to see new things, even if you’re not writing directly about them.

Which authors do you admire most, and which ones shaped your own writing?

Oh my gosh, where to begin . . . I am a huge fan of, in no particular order, Virginia Woolf, Edith Wharton, Alice McDermott, Tom Perrotta, Meg Wolitzer, Richard Yates, Evan S. Connell, Ann Patchett, Kate Atkinson, Alice Munro, Emma Straub, and Elizabeth Strout among many, many others.

Stephen King has said that he eats cheesecake before sitting down to write. Is there a type of food you eat in order to stimulate writing?

I wouldn’t say there’s a food exactly. Drinks, maybe. I drink a travel mug of English breakfast tea when I first sit down in the morning, then, after writing for a while, I take a break to walk my dog and I make myself a latte. I have one of those AeroPress coffee makers, so there’s a lot of ritual involved. And that’s all before I start frothing the milk.

Do you have a favorite place you like to write?

I write at my desk, an antique mission-style desk I bought when I moved from Maryland to DC. It’s in front of French doors through which I can see trees and the lovely coop across the street. I have several old books behind my laptop, some of which belonged to my father, including his rhyming dictionary; I also have two small ceramic renditions of my Goldendoodle Ginger, both made by my children; a small painting of a pear my daughter made, as well as a blue glass vase from a flea market in Florence, three beautiful old buttons from a flea market in Vermont, and my father’s watch. They’re my writing charms.

You worked on White Elephant for nearly fifteen years before sending it to a publisher. How did this story evolve over that time period? What was the most challenging part of writing it, and how did you overcome that? And how did you decide your story was finished?

It’s been nearly fifteen years since I started writing it, but I really only wrote it between 2005 and 2008. An agent tried to sell it at the time, but the bottom fell out of the stock market, which meant no one was building monster houses anymore. I thought the time for the book had come and gone, but when I pulled the book out again in 2017, I realized the topic had become relevant again in the intervening years. At the time I wrote it, White Elephant was just about a neighborhood in crisis, but now it feels like a microcosm of what’s going on in our entire country. We are so much more divided now than we were then.

In 2017 I took out one of the character’s voices, then I did some more edits with my agent and my editor, two of the most brilliant women I know. I was encouraged to put my characters at more risk—which is hard to do when you love your characters—but it definitely improved the book.

There are a lot of characters in the book, most of whom play a part in the book’s narration. It’s always an interesting puzzle to sew all of the voices and the plot pieces together—a challenge I adore. Generally, a book is finished when I can’t stand the sight of it anymore and feel as though I have to get it off my desk.

Do you have any advice to writers, like me, who are also seeking to publish their first novel?

Keep at it. I started writing fiction in 1990—nearly thirty years ago! There are many times I wanted to give up, and even did give up for short periods of time, but I kept coming back to it. That’s my biggest message, if you really want to do it, be The Little Engine That Could. Keep honing your craft and putting yourself out there.

Similar to Revolutionary Road, Richard Yates’s novel about the darker side of a prosperous suburb, several of your characters are involved in a community theater production. Is there any significance to your choice to use the musical Annie Get Your Gun?

There’s something so pure about community theater: neighbors put on costumes and create art together for no other reason than the sheer joy of it. To create any kind of theater you have to work together, to compromise—which does not come naturally to my characters, so naturally, I wanted to see them try their hand at it.

My kids were involved in theater when they were young, and my daughter was in a community theater production of Annie Get Your Gun. It’s so over the top and the music is so fun. It seemed like the perfect show for the denizens of Willard Park.

Several of your characters seem shallow at first, then later display surprising depth. One of my favorites is Kaye, a former sorority girl who secretly paints in response to her mother’s lost battle with breast cancer. Where did you get your inspiration for the “mammographic” paintings? (Great name, by the way!)

Thank you! I don’t know where those came from, actually. Kaye just started painting them one day . . . I have a soft spot for Kaye, too. She means so well, but she has so much trouble reading people and situations. She has a lot of potential I think, but she never quite received the love she needed. I still have hopes she’ll eventually find her way.

Is there one message you’d like readers to come away with?

I’m fascinated by the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, and the stories we tell ourselves about other people. We have so much trouble communicating, even with the people we love the most; when it comes to people we disagree with it’s even worse. I feel as though people are pretty similar on the inside. We all have fears, and feel shame, and we want to succeed (though our definitions of success vary). We all want to be seen and loved—that’s the main thing. I’m hoping the book will remind people that we are not all that different. If we get to know one another a little better, even those whose points of view are quite different from ours, we might find common ground and begin to make some positive changes together.

Can you talk about what you’re working on now?

I’m working on another comedy set in a different fictional suburban Maryland town. You can take the girl out of the suburbs, but you can’t take the suburbs out of the girl, apparently.