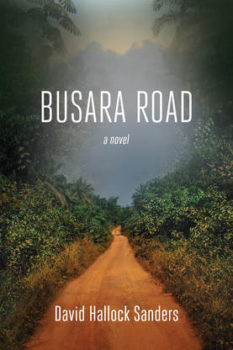

David Hallock Sanders’ debut novel, Busara Road (New Door Books), is a coming-of-age story set in Kenya in 1966, told from the point of view of eleven-year-old Mark, a Quaker from Philadelphia. The boy first observes and later participates in dramatic events in the small Quaker mission village of Kwetu on the Busara Road. Trauma marks both Kenya’s past and Mark’s recent experience. The boy is an uprooted only child whose mother has died after a long illness and whose father has chosen to move the two of them to a Quaker educational mission at Kwege—despite continuing intra-Kenyan hostilities and some hostility toward Western outsiders.

As a boy, the author lived on a Quaker educational mission in Kenya with his parents and siblings. Speaking with his publisher, he said the novel grew out of his interest in “exploring the experience of a young person coming of age in a nation that is coming of age itself.” Like his protagonist, the author was “young enough to be embraced as a child and be given access to aspects of local life not available to adults.” But also like Mark, he was ignorant of the country’s history: “the atrocities of the British Emergency and the cruel conditions of colonial control,” as well as Kenya’s “long and bloody fight for self-determination.”

As a boy, the author lived on a Quaker educational mission in Kenya with his parents and siblings. Speaking with his publisher, he said the novel grew out of his interest in “exploring the experience of a young person coming of age in a nation that is coming of age itself.” Like his protagonist, the author was “young enough to be embraced as a child and be given access to aspects of local life not available to adults.” But also like Mark, he was ignorant of the country’s history: “the atrocities of the British Emergency and the cruel conditions of colonial control,” as well as Kenya’s “long and bloody fight for self-determination.”

Limited knowledge, understanding, and perspective are among the inherent challenges for a novelist employing a child’s point of view, especially in historical fiction. It is additionally challenging, even risky, to draw closely on personal childhood experience. After all, “what happened” doesn’t necessarily lend itself to the arc of story. Yet Sanders successfully navigates these challenges, in part by using memory as inspiration and jumping off point, exposing Mark “more directly to the dark repercussions” of Kenya’s past than he was himself during his much more secure childhood sojourn.

This dramatization is evident from the beginning of the novel, when Mark witnesses a scene on his first afternoon in Kwetu that will foreshadow mystery and violence to come. Sanders writes:

A bare bulb hung from the ceiling. Its harsh light revealed two African men. One of them sat on a wooden chair…He wore a shirt decorated with circles of color that exploded like fireworks…The standing man wore a short-sleeved khaki shirt that revealed a stump of flesh hanging where his right arm should be. He gripped something that caught the light—a straight razor…With a single flourish, he swiped the razor across the other man’s throat.

At this point, neither Mark nor the reader realizes that this startling inter-personal episode also reflects the historical and cultural context of current Kwege. However, over the course of the novel, Mark learns something of Kenya’s colonial legacy and recent past, piecing together information most often provided—and filtered—by the family’s cook, Chege, who has his own shadowy backstory. In this same fragmentary manner, the reader learns alongside Mark as he comes to slowly understand (however incompletely) the way history inflects the present moment. Here, for example is an introductory toast from the Independence Day dinner—a social occasion which shortly afterward devolves into argument over the past:

Dr. Mathenge lifted his glass once more. ‘To our young nation. To our esteemed liberator and president, Mzee Kenyatta. To all who have suffered and died for our independence. To land and freedom. Ithaka na wiyathi…”

Mark is confused, overwhelmed, and fascinated by Kwege, a community of aspirant Kenyan and Western Quakers with limited resources and sometimes divisive beliefs but a shared zeal for education. He plunges into the pre-teen struggle to be accepted, to make friends, to understand kinship and friendship systems—in a complicated multi-racial and multi-cultural foreign milieu. The cook Chege becomes his caretaker as his father increasingly travels on mission business. Chege teaches Mark something of the rules and history of the community, but often seems secretive to Mark. The reader increasingly understands Chege’s urge to protect Mark from knowing too much. Indeed, one of the pleasures of a story told from an immersive child point of view is sometimes being more aware of Mark’s danger than he is himself.

“My mother used to say “Fuata nyuki ule asli.” Follow bees and you will get honey. But that means nothing to these young people…they just go to the shops and buy things.”

“But how did you learn so much about the jungle…the Mau Mau lived in the forest. Were you Mau Mau?”

Chege stared into the trees for a long moment.

“That is not a good question to ask.”

Similarly, the stakes of the novel are elevated in part by the tension between the risks that Mark is facing and his awareness of those risks. His father away, and Chege preoccupied, Mark runs a bit wild with a group of Kenyan and American peers. He and his friends range freely after school hours and he becomes involved with a troubled Kenyan girl, gradually learning a little of what she suffered physically and emotionally during conflict between the Mau-Mau and Kikuyu. The culmination of this trajectory Mark is on will lead to a dramatic and dangerous climax, one that his father will recognize almost too late, bringing about a sudden end to the novel.

It’s a conclusion that some readers may wish were further developed. Yet despite its abruptness, the conclusion is perhaps consistent with the author’s choice to tell a story as experienced by a child. The author has said that Busara means “wisdom, insight, and common sense” in Swahili and that the Busara Road is “Mark’s own path to wisdom and insight.” But only to a point. For while Mark’s understanding may have deepened over the months, he remains only a wiser child, not an adult, by story’s end. Self-determination is a long process, for nations and for people. The author’s unmediated immersion in Mark’s point of view similarly captures the way a child feels like a token moved from square to square on the adult’s game board. The author’s conclusion—despite but also because of its abruptness—thus rings true to a child’s experience. Mark is, after all, a child with a child’s limits to agency and self-determination, even if he is rapidly careening along the continuum from innocence to experience, childhood to adulthood.