Editor’s Note: Peter Turchi’s essay on narrative distance in third person fiction begins with an examination of Jai Chakrabarti’s “A Small Sacrifice for an Enormous Happiness.” He writes,“Chakrabarti’s technique is Chekhovian: he draws us close to his main character, withholding any overt judgment, instead guiding us so that we see the character’s flaws, and allowing his narrator to give the story not only shape but depth through the careful selection of detail.”

You can read Part I of this essay here. Part II of the essay continues below.

Testing the Limits: A Stronger Narrative Presence

Chakrabarti’s story employs a narrator who does his work, for the most part, without drawing attention to himself. The narrator in this next example makes bolder choices, is more assertive, and steps beyond a single character’s point of view at moments, but stops short of expressing opinions, or telling the reader what to think.

Jenny Erpenbeck’s Go, Went, Gone (New Directions) tells the story of Richard, a widowed and recently retired classics professor in Berlin who becomes aware of African refugees staging a hunger strike. Over time, he interviews many of the men, helps them find ways to make money, to get health care, and to get necessary legal representation; eventually he invites several of them to live with him. But that summary sounds overly romantic: what Richard and the reader come to understand is that the struggle of most of these men is, if not futile, Kafka-esque in its frustrations, as European laws make it difficult, if not impossible, for African refugees to become citizens, or even to be legally employed.

To some extent, Richard is a stand-in for the reader: we learn what he learns, and the book largely follows his curiosity, his discoveries, and his decisions. For the great majority of the novel, we are, if not in Richard’s head, his close companion. The book begins with his thoughts and ends with an admission he makes only as a result of a conversation with one of his closest friends and several of the African refugees he’s taken in.

Along the way, though, Erpenbeck shifts narrative distance, sometimes almost imperceptibly, sometimes dramatically. These shifts ultimately govern the novel’s thematic development, its meaning-making. Erpenbeck prepares us for them, subtly, from the very beginning:

Perhaps many more years still lie before him, or perhaps only a few. In any case, from now on Richard will no longer have to get up early to appear at the Institute. As of today, he has time—plain and simple. Time to travel, people say. To read books. Proust. Dostoyevsky. Time to listen to music. He doesn’t know how long it’ll take him to get used to having time. In any case, his head still works just the same as before. What’s he going to do with the thoughts still thinking away inside his head?

The opening paragraph continues along these lines, situating us very close to Richard, creating intimacy through colloquial syntax, approximating his thoughts, but without adopting his voice.

The opening section closes, “From his desk, he sees the lake.” At first, this seems like an innocuous detail—he has a nice view. But Erpenbeck ends the section with that fact to give it emphasis. Over the course of the novel, the lake will become a powerful metaphor. But it isn’t a metaphor for Richard; for him, it’s simply a fact. Two pages later, he contemplates what he should wear and how he should take care of himself now that he “no longer goes out in human society on a daily basis.” He thinks he can stop shaving: “Let grow what will. Just stop putting up resistance—or is that how dying begins?” He rejects that notion, but his thoughts immediately turn to the lake. Or, rather, that’s what the narrator suggests. Here’s the passage:

…Just stop putting up resistance—or is that how dying begins? Could dying begin with this kind of growth? No, that can’t be right, he thinks.

They still haven’t found the man at the bottom of the lake…

The narrator goes on to tell us that the man, a swimmer, drowned in June; since then, the lake has been “perfectly calm,” in part because of the weather, in part because locals have avoided going into the water since the accident; only outsiders, people who don’t know about the drowning, swim in it.

Richard has never mentioned the accident to an unsuspecting visitor: what would be the point? Why ruin things for someone who’s just trying to enjoy the day? Strangers who walk past his garden gate on their outings return just as happy as they came.

But he can’t avoid seeing the lake when he sits at his desk.

It’s up to the reader to draw the conclusion that the lake represents not only the death of a stranger, but Richard’s inevitable demise. That suggestion is made entirely by the narrator, in the rewording of a statement of fact.

The lake will take on greater meaning as the novel progresses.

In the next section—still in the first chapter—we learn that local gossip has it that some people were out in rowboats when the man drowned, but didn’t try to rescue him—either they didn’t understand the seriousness of his trouble, “or maybe they were afraid the man would pull them down with him, who knows.” That casual “who knows” might throw us off the scent, and this early mystery—the identity of the drowned man and the circumstances of his death—is never resolved. Instead, Erpenbeck lets these early references to the drowning establish a darkness in the background, one that she’ll develop in ways that Richard never recognizes, or at least never acknowledges.

As you might already have intuited, the anecdote about the drowned swimmer in the lake is analogous to the story of the African refugees in the middle of Berlin. Some people ignore them; some may not understand their plight; and eventually they’re moved out of sight. But this analogy can’t be evident to the novel’s reader—not yet—because the African refugees haven’t even been mentioned.

As you might already have intuited, the anecdote about the drowned swimmer in the lake is analogous to the story of the African refugees in the middle of Berlin. Some people ignore them; some may not understand their plight; and eventually they’re moved out of sight. But this analogy can’t be evident to the novel’s reader—not yet—because the African refugees haven’t even been mentioned.

The ambiguous distance between narrator and point of view character is more fully defined in the second chapter, when the narrator tells us that ten men, who speak English, French, and Italian, as well as other languages “no one here understands,” and whose skin is black, have gone on a hunger strike. Some of the men have also decided not to speak, not to answer questions put to them by the police and others. She tells us, “The silence of these men who would rather die than reveal their identity unites with the waiting of all these others who want their questions answered to produce a great silence in the middle of the square…”

In the next paragraph, the narrator asks, “Why is it that Richard, walking past all these black and white people sitting and standing that afternoon, doesn’t hear this silence?” That quickly, the narrative establishes a much longer view—she is speaking directly to us about her main character. Only in the third chapter, when Richard sits down to watch the news at home, does he learn part of what the narrator has been telling us about the African refugees.

From that moment we might expect the novel to operate differently; we might think the narrator has more she wants to tell us, that she might start interjecting like Jane Austen, or Dickens. But in fact the novel stays close to Richard’s thoughts, questions, concerns, and actions. Erpenbeck has established her options, though, and throughout the novel her narrator occasionally draws back to tell us other things Richard doesn’t know, as in this passage:

The professor emeritus, who’s hearing so many things for the first time that it’s as if he’s become a child again, now suddenly understands that Oranienplatz is not only the square designed in the nineteenth century by the famous landscape architect Lenné, not only the square where an elderly woman walks her dog every day, or where a girl on a park bench kissed her boyfriend for the first time. For a boy who has grown up among the nomads, Oranienplatz—where he made his home for a year and a half—is one station on a long journey, a temporary place, leading to the next temporary place.

“The professor emeritus” is Richard; Erpenbeck uses that label to signal a shift to the stance she introduced much earlier—here, to underscore the fact that Richard’s is the story of an education, even if the man being educated is a retired professor.

Late in the novel, Erpenbeck puts this greater distance to dramatic use in two ways.

In the final scene, during a party at Richard’s house, he learns that the wife of one of his best friends, who has been ill, is now close to death. The friend, the woman’s husband, is at the party; and when the news spreads, all of the guests, German and African, fall silent. (A reminder: all of the African refugees are men.)

One man now thinks about how his wife always kissed him on his eyes.

One thinks how well the woman he loves always fits in his embrace.

One man thinks about her running her hand through his hair, and another how good her breath smelled when her face was beside his.

One thinks how his wife stuck her tongue in his ear…

All of them think for a moment about women they have loved, who once loved them.

This leap to the other men’s thoughts is surprising; at the same time, we realize the narrator has prepared us for it, has given herself the option of telling us things Richard doesn’t know, since that moment in the second chapter, when she asked why Richard hadn’t seen the men in the plaza—and then told us.

On the final page, Erpenbeck does something even more surprising. If you haven’t read the book, it would significantly impact your experience of it. So I’ll say only that Erpenbeck first tells us something that Richard may or may not know; then she tells us something that he certainly knows, something he has known all along, information about his past that dramatically changes what we thought we knew about him. It’s as if something long suppressed has surfaced. The novel ends with these lines:

I think that’s when I realized, says Richard, that the things I can endure are only just the surface of what I can’t possibly endure.

Like the surface of the sea? asks Khalil.

Actually, yes, exactly like the surface of the sea.

All of the refugees have had to cross the sea; many of them saw friends and family members drown. And of course Richard can’t avoid looking out at the lake, which the narrator tells us “will forever remain the lake in which someone has died, but it will nonetheless remain forever very beautiful.”

And so in the end of the novel Erpenbeck draws together multiple narrative threads, but also the pain of knowing, the impossibility of forgetting, temporary forgetting, and the unbearable knowledge that lies beneath ordinary, and even beautiful, surfaces. She’s done that by leading us deep into the thoughts and experiences of a compassionate, curious, educated, but clearly flawed man; and she’s done it by allowing us to see what he sees, but also more than he sees, and differently than he sees. The result is a novel that demands, and rewards, the reader’s active participation.

Erpenbeck’s narrator doesn’t tell us what to think, doesn’t explicitly pass judgment; she guides us almost entirely through the selection and arrangement of information.

The Claustrophobic Stance

Given the title of this essay, it might seem contradictory to advocate standing even closer to your point of view character; but in the same way that a stranger’s standing too close in conversation—violating our “personal space”—creates tension, and has us thinking about more than whatever that person is saying, deliberately limiting the reader’s perspective to that of a character with limited or biased insight can be useful in making the reader alert to what’s being withheld, or what isn’t apparent to the main character. “Deliberately” is the key word—for any of these techniques to succeed, our proximity to the point of view character has to be intentional, strategic, serving the story’s ultimate purpose. These claustrophobic narratives stand so close to their point of view characters that we don’t know what the characters don’t know, we can’t see what they can’t see—until the narrator chooses for us to see, or understand, something more. The keys to this strategy are to make the reader aware that the character is blind to something—and then finding a way to reveal it.

In some of these stories, the narrator also obscures things the character can see (just as Chakrabarti’s narrator withheld the fact that Nikhil was preparing to tell Sharma that he wanted a child). The result is that we sometimes feel stranded, abandoned, unsure of what to make of what we’re reading; but the best of these stories pay off brilliantly.

Adam Johnson’s “Hurricanes Anonymous” tells the story of Randall, a twenty-six-year-old UPS driver in Lake Charles, Louisiana, soon after hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Randall has been evicted from the house he was renting; has had his truck stolen by his father; has had his wages garnished by his former girlfriend, who became pregnant by him and bore the child; has recently been forced to take responsibility for the child; and has a new girlfriend, Relle, who, thanks to the hurricanes, is temporarily living in a halfway house.

To a large degree, “Hurricanes Anonymous” reads like a straightforward close third person narrative. But Johnson puts that “closeness” of the close third person to use in at least two surprising and significant ways. Johnson’s narrator is something of a trickster, carefully manipulating what we know and what we think we know about Randall.

Johnson doesn’t necessarily explain to the reader things that Randall knows but has no reason to think about. A simple example comes in the first two sentences:

[Randall] pulls up outside Chuck E. Cheese’s and hits the hazards on his UPS van. The last working cell tower in Lake Charles, Louisiana, is not far away, so he stops here a couple of times a day to check his messages.

We don’t know why Lake Charles has been reduced to one working cell tower; Randall does, and he’s been living with the fact for a while, so there’s no explanation.

But this sort of withholding is not uncommon in the opening of a story. More surprising is something that happens near the middle. Randall and his girlfriend, Relle, are having a conversation when they discover that Randall’s young son has somehow loosened the lid to one of the shipping containers, and the UPS van is now filled with live crawfish. “We’ll talk about it tonight,” Randall says. Relle says, “At A.A.?” “Where the hell else,” Randall answers.

When we get to the A.A. meeting, it comes as a surprise that neither Randall nor Relle is a recovering alcoholic; they attend the meetings, we learn, because A. A. offers free childcare, and that allows them the opportunity to make love in Randall’s van. The surprise to us is the result of a clever move on Johnson’s part: Randall knows perfectly well why they go to the meetings; but he had no reason to “think it” while he was corralling crawfish. Johnson’s narrator didn’t let us draw a false conclusion by mistake—he set us up for a surprise. Throughout the story, this sort of intentional withholding of information keeps the reader slightly off balance, building tension and suspense.

One of the challenges of the claustrophobic third person is conveying what the point of view character doesn’t know, or fails to recognize, in a way the reader can trust. In “Hurricanes Anonymous,” Johnson uses repetition to make one of Randall’s blind spots apparent.

One of the challenges of the claustrophobic third person is conveying what the point of view character doesn’t know, or fails to recognize, in a way the reader can trust. In “Hurricanes Anonymous,” Johnson uses repetition to make one of Randall’s blind spots apparent.

Three times in the story—at the beginning, in the middle, and in the last third—a minor character indicates to Randall—and so to us—that he or she is concerned about his son’s condition. Early on, Randall makes a delivery to a friendly electrical engineer who makes conversation with the boy, and reveals he has a son the same age. We see the scene from Randall’s perspective, as he observes the work site, so we’re caught off guard when the engineer says, “Obviously, you two are in some kind of situation, but seriously, the boy can’t be running around in his jammies. Look at the glass and nails. He needs some boots and jeans, something.” Until that moment, we didn’t know the boy was barefoot, and Randall had taken no notice of the glass and nails.

At the AA meeting, after Randall and his girlfriend make love, they go to collect the boy and find that the older women have done much more than babysit—they’ve given him a bath and a haircut and a hand-me-down set of overalls, and “they’ve applied thick cream to his sunburned face.” Until that moment, we had no idea that he was so obviously in need of a bath and a haircut; but now we understand that the earlier scene with the friendly engineer wasn’t an exception: despite all the attention Randall gives his son, he is not up to speed on some of the basic elements of parenting.

Much later, Randall asks Dr. Gaby, a woman who works at the halfway house where his girlfriend lives, to take care of his son while they go to visit Randall’s father. Randall insists that he’s coming back, and he’s sincere; but Dr. Gaby clearly believes otherwise: “You understand that if you leave this boy with me, I’ll have to do what’s best for him. That’s what will make the decisions.” She has him write out a note giving her temporary guardianship; but first she says, “Randall. Do you know what you’re doing?”

Randall believes he does. But thanks to his interactions with the engineer, the women at the AA meeting, and Dr. Gaby, we’ve slowly come to understand that he does not; and through scenes with his girlfriend, Relle, we understand something else he does not: she has been lying to him about her plans for their future.

One of the key indicators of whether a narrator (and writer) is seeing beyond the limits of the point of view character’s perspective is the role of secondary characters. Johnson uses secondary characters to expose what Randall is missing—just as Tripti and Sharma challenge Nikhil’s perspective in “A Small Sacrifice for an Enormous Happiness.” Often, problems with third person limited stories stem from our aligning ourselves with the perspectives of our main characters to the point that we don’t fully consider how the world they’re in might challenge them, or conflict with their attitudes and actions. (If you think you’ve gotten too close to one character’s perspective, you might ask yourself, What does each character in this story think of every other character? Why? What does he or she disapprove of? How does that character express her reservation?)

At the end of “Hurricanes Anonymous,” Randall—a character we’ve come to like— abandons his son. To help us understand why and how this good-hearted young man makes such a terrible mistake, Adam Johnson needs to carefully guide us through the story, allowing us to see the world as Randall sees it, but also allowing us to see more.

That’s what stories written from this point of view have in common: while we might call the point of view “limited” third person, because it gives us access to only one character’s thoughts, the story itself is not limited to the point of view character’s understanding.

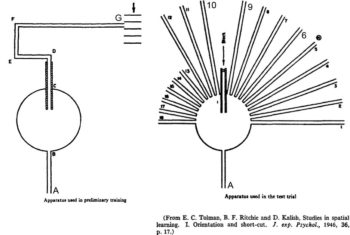

One last thought: you’re probably familiar with the old science experiments involving rats in mazes. The maze was in a wooden box with a transparent lid, so researchers could watch what the rats did. One of the earliest experiments involved putting a rat in the box, and a piece of cheese somewhere in the maze, and having the rat find it by exploring the maze—then, some time later, putting the same rat in the same maze with the cheese in the same place. The idea was to see if the rat could “learn,” or remember, how to reach the goal.

At some point in the drafting and revision process, we have a main character, and we know that character is going to make certain right and wrong moves, certain decisions, and encounter certain obstacles, and we know where that character is going to end up. And that’s when the trouble starts—because we might, in fact, write a story that is the equivalent of putting a GoPro on a rat, documenting his or her journey.

But here’s something to keep in mind: any number of rats outwitted that first experiment. In one case, a particularly ingenuous (or impatient) rat, placed for the second or third or fourth time at the start of the maze, simply stood up, raising the lid, and walked directly to the cheese.

After observing this sort of behavior, in the 1930’s, Edward Tolman proposed that rats were capable of “building [mental] representations of their environment”…the cognitive map a rat made “wasn’t just a strip map of the particular paths that led to the food but a comprehensive map that included the location of food and the surrounding space, enabling [it] to find novel routes.” Novel, indeed.

In other words, Tolman thought rats were a lot like us. The first “aerial view” maps of cities were made long before the airplane was invented, long before hot air balloons; in Arctic Dreams, Barry Lopez includes a detailed map of part of the Alaskan coastline as seen from above, drawn by a native fisherman who had never left the ground. This is what all of us, and particularly artists, do—construct an understanding of the world larger than a mere documentation of our own experience. We intuit, we infer, we gather information. Among other things, this allows us to imagine effects of actions we might take, and it allows us sympathetic understanding. It allows us to create fiction and poetry that, even if it is based in some way on our experience, speaks to readers we’ve never met—many of them quite different from us.

After studying rats, Edward Tolman extended his thinking to people. He promoted the notion of “broad cognitive maps,” maps that he hoped would lead us to recognize, for instance, that the well-being of all people is mutually interdependent.

While our characters might very well be narrowly focused, for any number of reasons, we, as writers, and our narrators, need to continue to build broader maps of the world of our stories—so that, when it’s necessary, we can create a few roadblocks for the reader; and when it’s helpful, we can raise the lid, and point straight to the cheese.