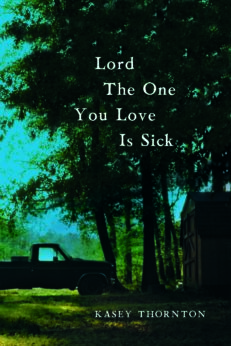

“I’m really interested in questions that have no answers,” Kasey Thornton told me at the beginning of our recent conversation about her debut story collection, Lord the One You Love Is Sick (IG Publishing) “Do we forgive people who abuse us? Do we interfere in situations where we know someone is at risk of being hurt? Do we stay in small towns that do not accept us, or do we leave? I don’t know.”

These questions, alongside a host of conundrums that belie easy resolution, are at the core of Thornton’s first collection, set in the fictional town of Bethany, North Carolina. Both gritty and gripping, the book opens with the death by heroin overdose of twenty-three-year-old Gentry, and then spins out to provide an insightful glimpse into the impact of his demise on people including his mother, brother, and best friend. In doing so, the stories wrestle with the contradictions of a place: kindness and generosity on one hand, religious hypocrisy and violence on the other. It’s a potent and thoughtfully-wrought combination.

Interview:

Eleanor J. Bader: In the publicity material for the book, you’re quoted as saying the following: “I write primarily about social issues—abuse, mental illness, addiction, gender roles, and grief—that are handled far differently in Southern culture than the rest of the world.” Let’s start there. What do you see as the South’s unique response to these issues?

Kasey Thornton: The problems I write about exist everywhere, from Timbuktu to New York City, but the South faces them differently. Growing up, a line I heard repeatedly from members of my faith was “don’t claim it.” What this means is that if you have a problem—say, you get into an accident or have an addiction—what you need to do is turn your problems over to God and they’ll be gone. If they don’t disappear, it’s because you didn’t trust God to help you. This type of reasoning discourages complex thought and rests on easy answers, as if the Bible is all that’s needed. Essentially, it says if you ignore the problem it will go away.

Nettie, Gentry’s mother, refuses to do this. She stops going to church, basically saying, “My son died and God hasn’t taken that away. I don’t have to act like I’m okay.”

Dale, Gentry’s best friend, is devastated when Gentry dies and feels guilty that he did not reach out and intervene to help him. How does this square with the “don’t claim it” ideology?

Dale, Gentry’s best friend, is devastated when Gentry dies and feels guilty that he did not reach out and intervene to help him. How does this square with the “don’t claim it” ideology?

Lots of people have these abiding friendships where they’ll mow your lawn or bring you groceries if you’re sick, but they won’t rush in to fix your problems, even when you’re in real trouble. Dale might have had personal reasons for avoiding Gentry—he was, after all, enrolled in the Police Academy training to be an officer—but he also might have truly believed that the best thing he could do was hang back and let Gentry figure out what to do for himself. There are no right or wrong answers about what to do here.

There is also a pervasive idea that we can all pull ourselves up by our bootstraps, that we don’t need help from other people, and can find our way independently.

Does this extend to drug addiction?

People don’t talk about drugs but then act surprised when someone uses. Every town is different. I have lived and worked in towns that have terrible drug problems. It’s strange. We had a pill issue in our town, but the town a few miles from us might have had a meth problem at that time. It basically depends on who is running the drug trafficking operation in a place and what they can get hold of at that moment.

Drug use in the South is an interesting animal. It runs counter to us not acknowledging our problems and expecting them to just go away . . . until someone like Gentry dies.

A secondary storyline in the book involves a brutally violent man named Jackson Hatcher who abuses his wife and daughters. Townspeople likely suspected that something awful was going on in the Hatcher home but no one said or did anything. Even when his eight-year-old daughter, Emma, is seen begging for food, her teachers do not report suspected neglect despite a legal obligation to do so. Is this another manifestation of “not claiming it?”

Yes. Everyone in town knew and respected Jackson Hatcher. He was the town mechanic and he did a good job on their vehicles. In larger urban areas, teachers likely don’t have a personal relationship with the parents of their students. In a small town like Bethany, they’d have to look Jackson in the eye—this man who fixes their cars and trucks, who may have dropped off a casserole when their mom died, or who sits next to them every Sunday in church—and accuse him of abusing his family. It’s a balancing act and they tell themselves that making inquiries will cause conflict and that is far worse than a child going hungry. Instead, they’ll just give the kid a sandwich.

It’s impossible to know how many children are pushed aside because people are afraid they won’t have a reliable mechanic to fix their truck if they report suspected abuse or neglect. That’s the social dynamic.

The abuse in the Hatcher home extended to Jackson’s sexual abuse of his daughters. Sarah, the girls’ mom and Jackson’s wife, had to know this was going on. On one hand, she’s a wonderfully compassionate nurse in the town’s psychiatric hospital. But on the other, she let her daughters suffer at the hands of her spouse. She’s a complex character.

One of the questions mothers of abused children are always asked is: “Did you know?” You get the sense that Sarah knows everything. I think her character reveals some of the most sexist aspects of life in the South. But she is also a victim. A person can be so abused and beaten down, with such low self-esteem, that she loses the ability to care for her children. Sarah is almost transmitting the care she can’t give her children onto her patients.

Let’s stay with sexism for a minute . . . Dale’s wife, Charlie, seems like a bit of a throwback, a woman who has little direction or drive to be anything other than a housewife. Is this accurate?

Well, we do not necessarily hear, “Women, get into the kitchen and make me a sandwich” anymore, but music shapes the culture down here and country music still talks about good women and bad women. A good woman is loyal, takes care of her man, and looks good in a bikini.

That said, I’ve known many women who are gentle, religious, and appear docile, but they’re some of the strongest people I’ve ever met.

As for Charlie, she fell so deeply into her husband’s problems she nearly drowned. She was on the cusp of figuring out what to do with her life when Gentry died and she got caught in the spiral of Dale’s grief, his depression and breakdown, and then his hospitalization and recovery. I hope to write a sequel to Lord the One You Love Is Sick, and if I do, Charlie will have her own arc, independent of her husband.

Speaking of storylines, why did you decide to write this as a novel-in-stories?

I like the idea of telling a story in the voices of multiple characters. I felt like I couldn’t appropriately explore Bethany and get into all the dirty corners without doing it this way. It felt more effective to have many different people—Nettie, Dale, Charlie, Ethan and other residents of the town—give readers their perspective on what was unfolding.

I also want to be clear about something else that I tried to do in the book. I think the South is worth fighting for, with all its issues. I think it’s worth fighting for change here. My family has lived in the South for more than 200 years and I intend to stay and help with the problems in whatever tiny way I can. I hope this book participates in that process.

When most readers think of Southern Literature, they think of the Southern Gothic. How do you see your work engaging (or not) in this tradition? Also, what Southern writers do you most admire or feel your writing is in conversation with?

I don’t see myself as engaging in the Southern Gothic tradition at all, really. It has very specific parameters that my book doesn’t touch on

In my earlier years I actually wrote a great deal of science fiction, historical fiction, dystopian fiction, etc. I explored genres because I didn’t think my boring life in my small town would be interesting to anyone. But then I read The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd, and was so enraptured by the way she made the South glow with all of its glory and devastation that I wanted to attempt it myself. Ellen Foster by Kaye Gibbons gave me full permission to write “Out of Our Suffering” through the eyes of a child, regardless of how difficult it was, and any ounce of humor in my novel, I got from This is Just Exactly Like You by Drew Perry, who captures the absurdity of everyday life with absolute hilarity and capital-t Truth. I appreciate any author or poet who zooms in on those subtle moments of humanity that come and go in a blink, but carry far more weight than we could ever know until an astute writer articulates its meaning.

Going back to the earlier idea of a distinctly Southern culture, can you talk a bit more about how a book like this helps reshape the conversation about this region?

There are ways of facing “modern” problems in the traditional South while still loving where you live, but it takes bravery, compassion, and understanding on all sides. I hope people walk away from my book with that knowledge, if nothing else.