When I teach creative writing, I often find myself talking about time. I’d ask of student work: When did this event happen? Did the protagonist kill her husband right after she discovered his infidelity or days later when she had fully considered the extent of his betrayal?

Fiction, I tell them, is interested in time. Not as an accounting of events or a compressed representation of drama but as a way of establishing causality and creating a narrative clock.

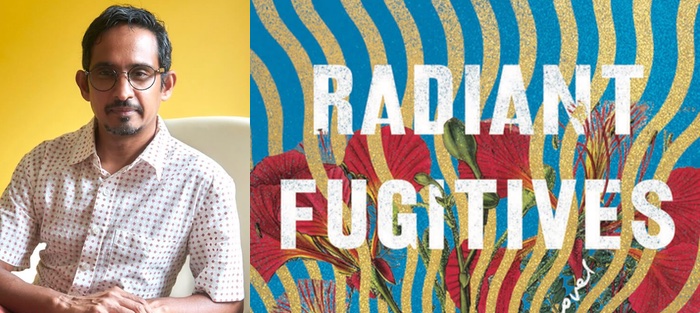

Nawaaz Ahmed’s Radiant Fugitives (Counterpoint Press) makes me think of Time in other, manifestly superior ways. Time, in his fiction, is a way of dressing characters. Uncovering motives and grievances. His characters reveal themselves over time, their actions acquiring new sympathies and synergies.

In this case, the fault lines being traced are in the relationships between a trifecta of women: Seema, a progressive campaign worker, Tahera, her deeply religious and jealous sister, and Nafeesa, their dying mother. Though it is Seema’s unborn son who narrates the entire novel. And it’s the compassion and love that the novel has for these women that makes it tick.

Nawaaz Ahmed is a transplant from Tamil Nadu, India. Before turning to writing, he was a computer scientist, researching search algorithms for Yahoo. He holds an MFA from University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and is the winner of several Hopwood awards. He is the recipient of residencies from MacDowell, VCCA, Yaddo, and Djerassi. He is a former Kundiman and Lambda Literary Fellow. He lives in Brooklyn. Radiant Fugitives is his first novel.

I spoke this past July with Nawaaz about some of the craft decisions that went into writing Radiant Fugitives.

Interview:

Nishanth Injam: The book is narrated from the point of view of an unborn baby. There is nothing this baby doesn’t know. It brings a quality of personalized omniscience and allows you to talk about any character. At what point in the journey of this book did you arrive at this voice? Was it always there?

Nawaaz Ahmed: I was trying to solve a few technical issues. I wanted to include the perspective of all the three women central to the book. Yet I didn’t want to use the same voice for all three characters and have them sound similar. I also didn’t want the narration to judge the characters and limit their possibilities.

One afternoon, it struck me that the best way to solve all these problems was to have an omniscient narrator who wouldn’t judge the women, and I ran through different choices and landed on the idea of the narrator being Seema’s unborn baby. The book started coming together from that point.

I’m really compelled by what you said about judgment. There were times when I found myself, as a reader, judging Tahera for her homophobia, and yet when I sat with her, all these other layers emerged, and I began to move past the judgment phase to a deeper understanding of who she was. You do that throughout the book—you move the reader’s understanding of characters; the reader is sort of led away from the ugliness of prejudice. How do you do it?

I’m really compelled by what you said about judgment. There were times when I found myself, as a reader, judging Tahera for her homophobia, and yet when I sat with her, all these other layers emerged, and I began to move past the judgment phase to a deeper understanding of who she was. You do that throughout the book—you move the reader’s understanding of characters; the reader is sort of led away from the ugliness of prejudice. How do you do it?

The book took me a long time to write, and one of the reasons I struggled with it was this judgment. I found myself judging. All the characters, all the time. That’s where the revision process came in. In each draft, I’d go in and see where I, the writer, was coming in, instead of the narrator or the character. Keeping that distinction alive in my mind helped me get there.

Writing Tahera was hard for me. She forced me to grow. She used to rankle me, and I wasn’t certain that I was being fair to her by making her do these things. I had to work through my own issues with her and the result is that I love her the most now!

I love that you were able to find this generosity within her, something we often deny to other people.

I wanted to be sure I gave opportunities for Tahera to be generous and that I wasn’t withholding these opportunities from her—generosity, not just in terms of Tahera, but also in terms of the writer giving the characters what they need. There were times when I had to be like, okay, let me be more generous to her. Let me give her this moment where she’s not completely stressed. I was thinking about it even in the last draft: Can I reduce the pressure on Tahera a little more so she can act more generously?

We hear bits and pieces of Naemullah, Seema’s father, who rejects her after she comes out to him, but we never get his perspective. Was it a conscious decision not to go deeper into his own homophobia and to limit the narrative to the three women? I’m curious about the limits of authorial generosity here.

You got me there! The novel for me was more about the present, and about the three women in America than the father. He does love his daughter. I think we can see his love for his daughter, and then he makes this decision to cut off Seema. I didn’t really want to go deeper into his perspective partly because of how Indian patriarchy functions. He is this god-like figure, and his word is the law, and you must accept it. It can be very hard to read people like him because they won’t really explain themselves. I wanted to retain that inscrutable quality.

The two coming-out scenes in this novel—where Seema comes out to her father and years later to her mother—are on top of each other, the narrative flipping between each other. What was your reason for this juxtaposition? Are you implying in some way that you never come out once? That these moments exist in an alternate timeline where every coming-out is a portal to all other ones?

Definitely. I mean you are coming out all the time, and sometimes you are coming out to the same people. Again, and again. Especially in families that don’t want to talk about it. I knew I had to write these key scenes, but I wanted to write them in a way that captured not just the drama of that moment, but also the ongoing trauma. I wanted to show that the earlier moment has haunted Seema all her life.

Writing the scene where she has this conversation with her father, I knew she was going to have the same conversation with her mother, and that both would have to come together even if there were many years between those scenes.

The book jumps back and forth in time quite a bit. There’s the family drama with Seema and Tahera and Nafeesa over the years, and there’s a section with Bill and Seema and their political activism during the pre-Obama years. How were you able to balance all these different timelines and emotional goals in the same book? What’s the secret to having them all coalesce together into one larger structural arc?

That’s a very good question because I think it’s the structure that allowed all these sections to coexist. In the beginning, I didn’t know if they’d co-exist. In my initial drafts, Bill and Seema’s chapters were interweaved with the rest of the novel and that didn’t allow me to see the arc for what it was. It was also interrupting the flow of the novel.

I wasn’t able to really develop Bill and Seema’s narrative until I separated their pages into a section. I really needed to find what it was that I wanted Seema and Bill’s story to be about. By taking it out, I gave myself permission to let it be a self-contained little thing by itself. I clearly needed to talk about their relationship, how it began, and how it ended. At the same time, I also wanted to talk about America because that’s one of the reasons why Bill and Seema get together. I wanted to chart their relationship—its rise and fall, how they came together in this larger political landscape of America in the 2000s—because I think Seema’s marriage to Bill is a political act. She marries him for several reasons, and one of them is that it is she sees it as a political act, and I wanted this to be mirrored in the structure of what happens.

There are these beautiful moments in the book where not a lot happens. Where the mother and the daughters are making biryani and doing each other’s hair—ordinary activities that occur within a family. The small joys of cooking and prayer and other shared delights. How does one create space for that sort of existence on the page without diluting narrative momentum?

Generally, you want to draw the reader in the beginning, and not have them put the book away thinking, Oh, nothing’s happening. In a paradoxical way, I felt like I’d have more space in the first third of the book to do that. Because I wanted the last third to be a headlong rush, with fewer things to break the momentum. So, I did it in the first. And, of course, I did want these quiet moments of connection for the characters because how else could I have them change?

Change comes in small moments of joy and small moments of connection. I had to allow the characters the space to negotiate their anger and resentment towards each other, as well as their love, and their desires and hopes. I felt I could capture all that in the small moments which are pretty quiet. In the first third of the book, I gave myself license to be expansive. The last third was more like, I’ve got to get you from here to the conflict. So everything increases the conflict and the momentum pushes you toward the coda.

Joy and connection had to be important. I didn’t want to shortchange what the novel was about. It wasn’t about the characters having fights and all those other things happening. For me, the real drama was in those quiet moments.